Bidenomics takes on government investment

The numbers are disappointingly small so far, but our mindset has begun to change.

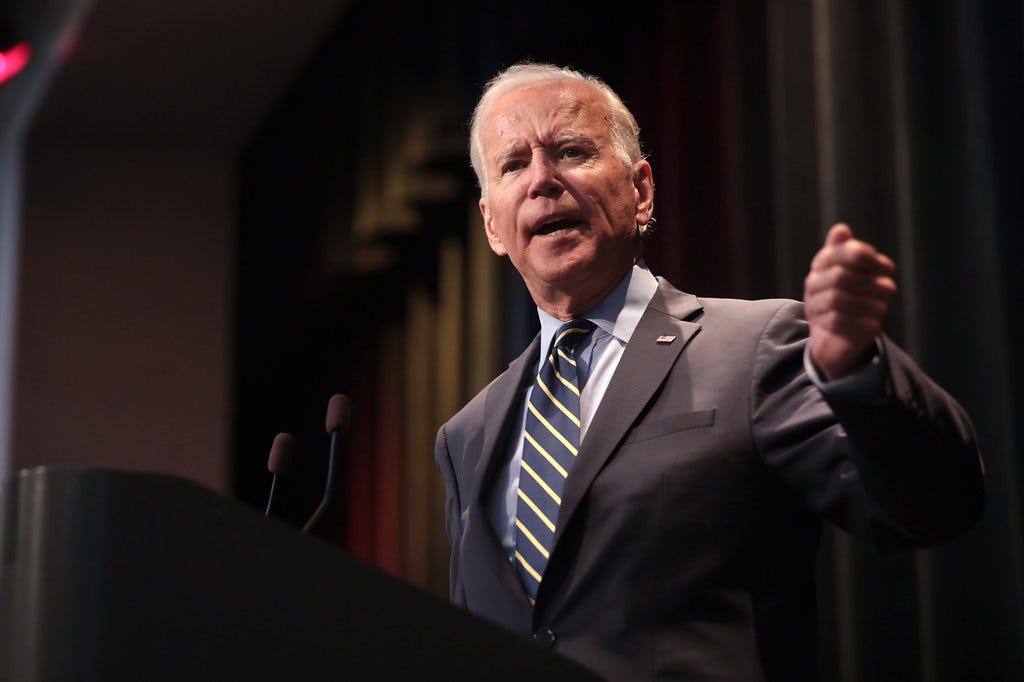

Back in April, I wrote a long post trying to summarize Bidenomics — that is, to generate a unified theory of what Biden and his people are trying to accomplish when it comes to economic policy. Instead of just a hodgepodge of progressive priorities, I saw a coherent program and vision.

As I saw it, the plan was to create a two-track economy — leverage government investment to support hyper-competitive knowledge industries that bring in revenue from abroad and preserve U.S. technological dominance, while using a combination of local service industries and government redistribution to spread around the wealth here at home. I think it’s generally a good plan, and it has the potential to make Biden’s presidency a transformative one.

The Covid relief bill made progress toward the second, “redistribution” track. If the bill’s special child “tax credit” — really a monthly child allowance — becomes permanent, it will make our welfare state more generous, simpler, more rational, and more universal. Along with similar bills under Trump in 2020, I think it might have changed the way Americans think about cash benefits.

Now Biden has moved on to the “competitiveness” track. His efforts here have so far been stymied by Republican reticence to spend. But they show small, encouraging signs of changing the way our leaders think about government investment. That shift in mindset could bear big dividends down the road.

The bipartisan infrastructure bill

The problem with the bipartisan infrastructure bill recently announced in the Senate is, well, partisanship. A lot of Biden’s agenda was left out, so there’s the natural impulse to put that stuff in a reconciliation bill (which doesn’t need GOP votes in order to pass the Senate). But let’s put aside the political maneuvering for a second, and just think about the bipartisan infrastructure deal on its own.

The bipartisan deal contains a pot of money to repair America’s roads and bridges, and build a few more besides. This is the way we usually do infrastructure in America. First we build a ton of roads and bridges that are highly expensive to maintain, especially with our ruinously high construction costs (see this recent article by Jerusalem Demsas). Then, because costs are so high, we wait for a long time to repair the roads and bridges, until civil engineers start screeching, roads get potholed, and there’s a bridge collapse or two. Then we muster up the political will to throw the requisite shit-ton of money at the problem, the potholes and weak bridges get repaired for twice the amount it would have cost had we done it on a regular schedule and three times the amount it would cost if we were a normal rich country. And the whole cycle begins again.

This is basically what the new bill does. And that’s fine — until we can fix our cost problem, that’s probably the best we can do when it comes to roads and bridges. But if this is all we do, it’s not really economically transformative.

The U.S. needs to transition to a low-carbon economy, and not just because to avert climate disaster. Many of the technologies that enable this transition — alternative energy, electric vehicles, energy storage, smart grids, and so on — are going to be very valuable industries in the years to come. By being a leader in the transition, the U.S. wouldn’t just score moral points — it would also gain competitiveness with respect to China. Thus, pushing green technology and green infrastructure is a very important form of government investment; in fact, even regulation, like Biden’s proposed clean energy standard, can be an investment-like policy in this situation, since it basically requires private companies to invest more.

The bipartisan deal, encouragingly, does have a little bit of this. Most importantly, it has $73 billion for electrical grid modernization — something private companies are not going to do on their own. On electric vehicles, it’s less ambitious, spending only a few billion on charging stations and electrifying only 20% of school buses.

And unfortunately, the bill leaves out the crucial clean energy standard (and also the various subsidies to fund the transition to the new standard). Without this big push, the U.S. will probably fall further behind in clean energy tech, especially energy storage.

Most damningly, the bill completely cuts out a planned $35 billion for clean energy research. Of all the things we can do to shore up U.S. economic leadership and competitiveness, leveraging our strength in research and development is the most important and will likely give us the most bang for our buck. To cut it out of a bill like this is pointless foot-shooting.

But despite the fact that it cuts out some big important elements (which will hopefully be pushed through reconciliation), the bipartisan bill acknowledges the importance of government investment, and recognizes the need for a shift to electric vehicles and green electricity. That’s a big step, and signals a change in mindset, especially among Republicans.

The U.S. Innovation and Competition Act

Which brings me to the U.S. Innovation and Competition Act. This is what the Endless Frontier Act was renamed when it was effectively gutted by Congress. Originally, this bill promised a dramatic increase in research funding — not nearly enough to return us to the percentage of GDP we spent on research in the 80s, but a solid step in that direction.

Once it passed through the meat grinder of legislative dickering, however, the bill came out looking far less impressive. It spends $190 billion; that might sound like a lot, but spread over 10 years it’s $19 billion a year, which is a less than a tenth of a percent of U.S. GDP. That reverses less than half the drop of the Great Recession, to say nothing of earlier declines:

But in fact it’s even worse, because the bill takes renewal of about $42 billion of existing research spending and labels it as new spending. Subtract that out, and the whole thing will raise U.S. R&D spending by perhaps .074%.

That is not going to be transformative. But the bill does have one saving grace — it establishes new research institutions. The new technology directorate of the NSF did wind up in the bill, even if it’s not well-funded. Ditto the regional innovation centers. The fact that these new institutions will now be created offers the opportunity of directing far more funding their way in the years to come.

This is encouraging because it also indicates a crucial change in mindset, especially among Republicans. By passing a bill like this, the GOP shows that it’s worried about U.S. technological competitiveness, especially vis-a-vis China. It’s not yet worried enough to spend the big bucks, but perhaps these things take time.

Reflecting on the New Deal and Reaganomics

In general, though I’m sad about the diminished size and ambition of these new Bidenomics initiatives, I’m optimistic about their direction. They both show a new paradigm emerging — a bipartisan recognition that government investment and government spending on technological competitiveness are both key components of a healthy economy. The shift in outlook is bipartisan, even if the GOP isn’t yet ready to fully open the public purse-strings on behalf of a Democratic President.

In fact, looking back on the New Deal and Reaganomics — our last two big policy paradigm shifts — we can see that they were substantively stymied in their early incarnations. Reagan’s 1981 tax cuts caused such high deficits that he had to partially reverse them in the following years. He never really made much progress on deregulation — in fact, more significant deregulations happened under Carter. It was only later, under Bill Clinton, that Reaganomics reached its full fruition, with financial deregulation and welfare reform.

Similarly, the New Deal faced pushback that temporarily limited its transformative power. Public works projects never blossomed into the full-fledged Keynesian stimulus that would have been necessary to lift the U.S. out of the Depression; it took WW2 to do that. By 1937 the country was back to punishing austerity, and New Deal initiatives basically petered out at that time. But the New Deal and the Second World War changed the relationship between Americans and their government, which led to big changes down the road — Medicare, the Great Society, the construction of the Interstate system, environmental and labor protections, and so on. Importantly, Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon embraced Roosevelt’s basic vision of economic policy — without their assent, it would not have made the deep, long-lasting impression it did.

In other words, these transformative economic policy programs often have much of their impact in the years after a president leaves office. On many points they fall victim to dogged opposition and status quo bias in the short run, but they change the way both parties think economic policy ought to be done. And that’s what really changes things.

In both of those previous cases, it was probably the challenges of the day that really made the shifts possible. New Dealism was a response to the Depression and WW2, and later to the early Cold War; Reaganomics was a response to stagflation, the energy shocks, and the challenge from a resurgent Soviet petrostate. In the same way, Bidenomics is our answer to Covid, to slowing growth, and — most importantly — to the competitive challenge from China.

And thus, if Biden can create a mindset change — a general bipartisan and popular acceptance of the type of policies needed to meet the challenges of the 2020s — he can leave a legacy that goes far beyond actual dollars spent. The recent set of investment bills give a glimmer of hope that this is already happening.

How come there's an apparent tendency in the US to cut research spending? Who's interest is that in? (Nobody's, it seems to me)

I fail to see anything resembling significant redistribution. Real wage growth is now negative and the 35% of Americans who don’t

own homes are facing exploding costs. No amount of credits or R&D or green energy is going to fix these structural issues which the administration chooses to ignore.