Beware shoveling money at overpriced service industries

Will we embrace "Cost Disease Socialism" instead of material abundance?

The other day I got a CT scan at UCSF, to check for possible aneurysms (don’t worry, I don’t have one). My insurance and I were charged a total of over $20,000 for this service. This is over 4 times the maximum price that most sources will list for a brain CT. Out of pocket, a CT scan can cost as little as a few hundred dollars.

Our politicians — both Democratic and Republican — are working on ways to curb surprise medical bills. That will be a good thing, but the problem runs much deeper. Ultimately, it’s about costs. The money my insurance company and I paid for my ridiculously overpriced CT scan subsidizes excess costs elsewhere in the health care system.

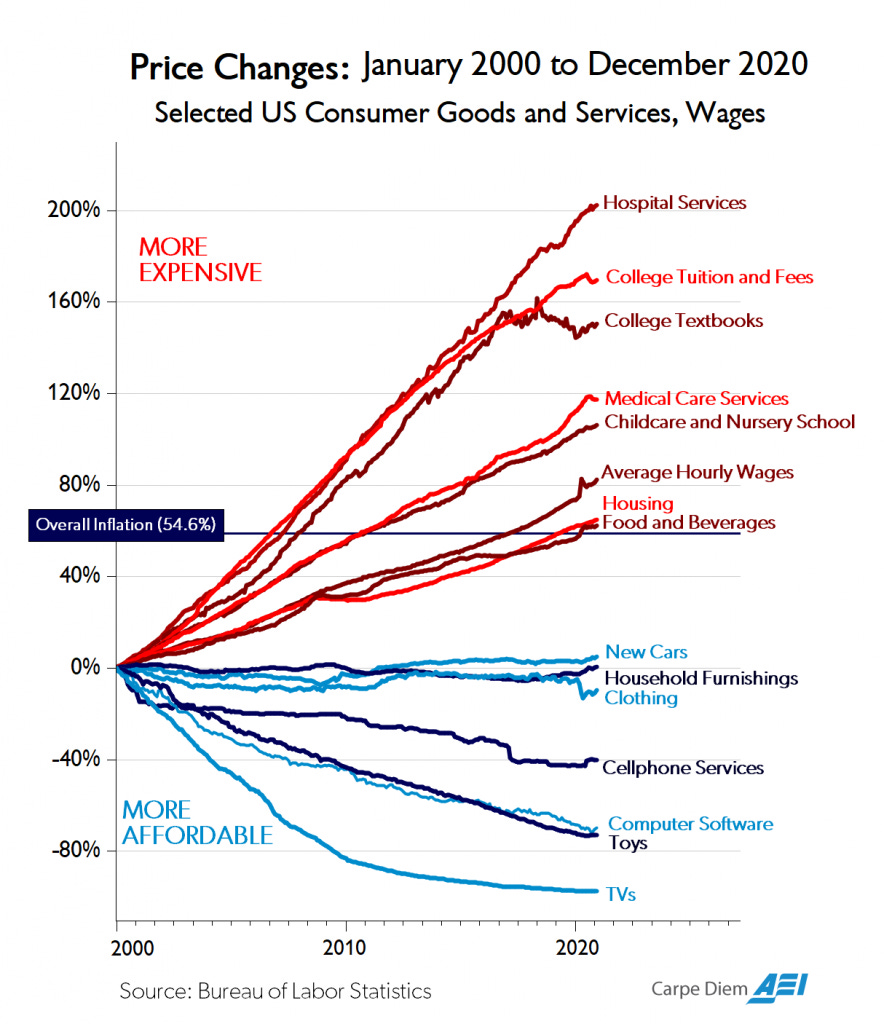

The U.S. is an outlier in terms of health care costs. Our system delivers similar outcomes to other countries’ systems, but we pay much more for those results — about 17% of our national GDP, compared to about 9%-12% for other rich countries. And the situation is getting worse, as health care prices outpace incomes. By now you’ve probably seen the famous cost graph from the American Enterprise Institute:

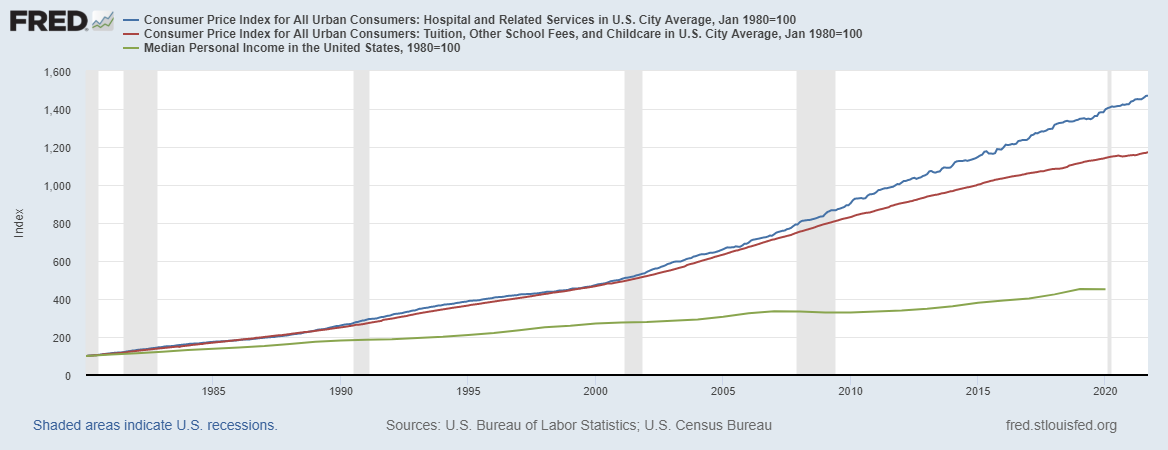

Prices for health care, education, and child care have strongly outpaced wages. Things don’t look much better when you compare these prices to median personal income:

Attempts to explain this via Baumol’s cost disease — the tendency of service-sector wages to rise as economies get richer — fall short, because the price of health care has gone up so much faster than wages (even when you compare just to college-educated wages). And attempts to explain health care prices as an income effect are also not credible, for many technical reasons (most glaringly, because A) they assume their conclusion by treating the U.S. as representative rather than as an outlier, and B) they rely on highly nonlinear single-sector models that predict that as countries get richer, they spend so much more on health, or whatever other overpriced thing is being modeled, that eventually all their other consumption goes to 0).

In other words, America is suffering from a unique sort of cost disease, and no one has yet come up with a credible or convincing simple explanation. And it isn’t just the big-ticket service industries — in addition to health care and education, the problem afflicts the construction industry, where productivity has stagnated or declined over time. These excess costs are crippling the country in a variety of ways — preventing us from building new housing, hurting transportation, raising the cost of labor in a variety of industries without actually delivering higher standards of living to workers, and so on.

We don’t yet know why this is happening (and I plan to write lots more about it), but at least people are starting to realize that it’s a problem. That’s good. In the meantime, though, there’s enormous pressure to relieve these costs by having the government pick up the slack and pay for more of people’s health care, education, and child care.

“Cost Disease Socialism” as a palliative

In a recent report for the Niskanen Center entitled “Cost Disease Socialism”, Steven Teles, Sam Hammond, and Daniel Takash warn against trying to salve America’s cost problem by subsidizing the overpriced stuff:

[T]he current vogue for “socialism” on the left is, on closer examination, almost always about socializing…common household expenditures. The traditional socialist call to “seize the means of production” has thus been updated to something closer to “subsidize my cost of living”…

Cost pressures in sectors like health care, housing, child care, and higher education are creating growing, irrepressible public demands to move such costs onto public budgets. Doing so would be a mistake, in our view, because the root cause of escalating costs is overwhelmingly regulatory, rather than budgetary, in nature. Shifting costs onto the public would not only fail to fix the underlying problem; it could also make cost disease substantially worse by shielding consumers from market prices while guaranteeing overregulated sectors a source of unconditional demand. This can result in a vicious cycle in which subsidies for supply-constrained goods or services merely push up prices, necessitating greater subsidies, which then push up prices, ad infinitum.

There are some big problems with the Niskanen thesis — in particular, its explanation for why costs are already too high. In construction, there is good evidence that regulation — especially rules allowing NIMBYs to block new projects — is a major source of excess cost. Regulation (especially rules mandating very low child-to-worker ratios) might be the issue in child care as well.

But in higher education, regulation is probably not the big problem. The supply of new university spots is not restricted — existing universities are free to increase the size of their student bodies, and frequently do so, while for-profit universities recently experienced a massive boom (that subsequently went bust after they turned out to offer poor value for money).

In health care, meanwhile, it’s obvious that in countries where medical services are much cheaper — i.e., every single other rich country — health care is more regulated than in the United States. In fact, price controls of one sort or another are a very common feature of other health systems, and are commonly cited as a factor that holds down costs. It’s easy to identify individual regulations that increase the cost of individual medical services, but economists who study the reasons for excessive health costs rarely point the finger at regulation as a big overall driver.

So Niskanen’s diagnosis for the existing cost problem is highly incomplete and needs a lot of work, especially when it comes to health care and higher ed. In addition, their worry that “subsidies…merely push up prices, necessitating greater subsidies, which then push up prices, ad infinitum” is perhaps a bit overblown (as long as supply is not perfectly inelastic, the cycle of prices and subsidies won’t be infinite).

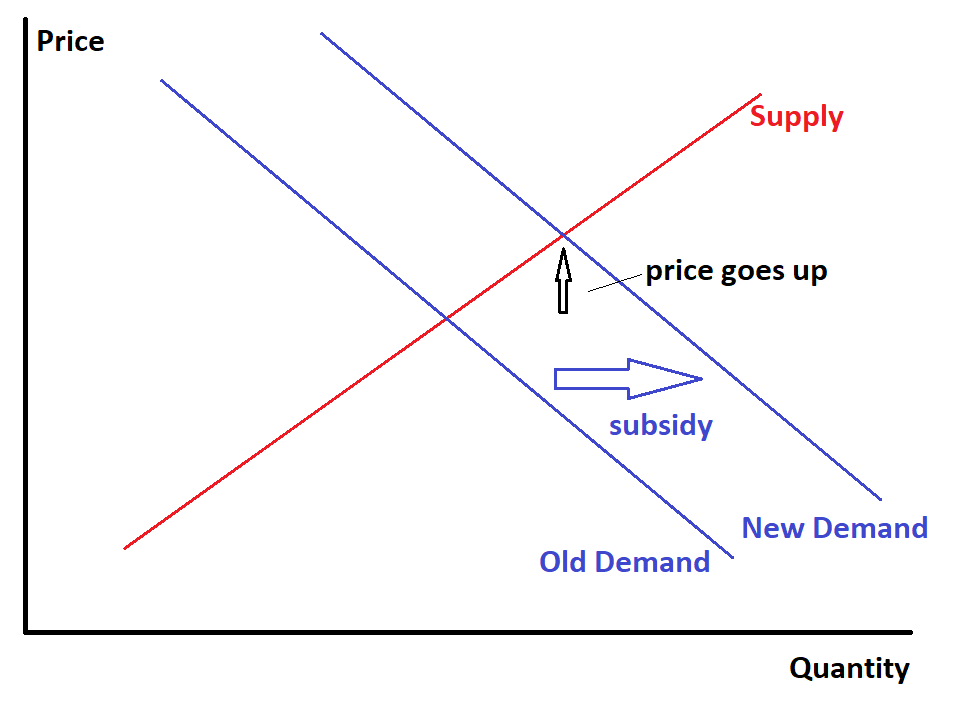

But if their diagnosis for the existing cost problem is lacking, Niskanen’s worry that palliative subsidies could exacerbate the problem is spot-on. Good old Econ 101 tells us that subsidies increase the prices of things:

(Of course this model doesn’t always hold in reality, but things like monopoly power and monopsony power won’t change the basic story in this case. It is possible that vouchers for specific goods would leave overall spending patterns unchanged, because people would simply shift their non-voucher spending to stuff the vouchers don’t cover; but in practice, this generally doesn’t happen. Meanwhile, subsidies that reduce the price that consumers pay for specific goods will push up the price that suppliers receive in pretty much any model.)

So if we try to deal with the problem of expensive health care, child care, and higher education by throwing more money at it, the result will be that although consumers will pay less, society as a whole will pay more. This is exactly what happened with student loans. The government offered people cheap student loans, which caused students to pay more for college, which caused colleges to hike their prices.

Now, you might say “That’s fine, as long as rich people are footing the bill and everyone else is getting the benefit.” America needs more redistribution, as Niskanen readily agrees.

But subsidies for overpriced sectors are a highly inefficient way of doing redistribution. If you just take cash from rich people and give it to poor people — as we did in the recent COVID-19 stimulus bills — they spend it on whatever they want. But if you distort the economy in favor of health care and higher ed and child care and so on, you’ll just end up wasting resources on these sectors. You’ll get more administrative bloat at colleges, more hospital workers and insurance industry workers doing hours of useless paperwork, and so on.

And meanwhile, the price increases in these sectors will eat up part of the subsidy, meaning that instead of a transfer from rich to middle class and poor, part of what happens will be a transfer from normal folks who work outside of health care and higher ed and child care to folks who work in these sectors (who may be highly paid execs, doctors, or shareholders).

In other words, “Cost Disease Socialism” really is something we need to worry about. It’s a way of dealing with inefficiency by piling on even more inefficiency. That doesn’t mean it’s complete waste — there is some transfer from rich to poor involved, and that is good — but it shouldn’t be our first option for dealing with high costs.

Two competing visions of a progressive future

In recent weeks, as Joe Manchin has threatened to gut Biden’s Clean Electricity Performance Program and Biden’s child tax allowance, I’ve felt a distinct sense of despair. Those two programs would transform the American energy system and the American welfare state in positive and needed ways. If Manchin succeeds in gutting them, it will be a sign that the United States has lost the ability to respond to major challenges with effective government action.

Progressives need to rally behind these two programs and fight hard to save them. But I also see progressives rallying to defend the Build Back Better bill’s health care subsidies:

It’s pretty certain that Biden won’t be able to get everything from his initial offer into the final bill. So progressives need to pick and choose which items they spend their effort and political capital to save.

Health care subsidies (and child care subsidies, and higher ed subsidies) are the wrong choice. Not because they’re bad — Medicare should include dental and vision, Medicaid subsidies would relieve some human suffering — but because they’re not the best things in the bill. They represent Cost Disease Socialism — relieving the economic burdens of lower-income Americans by buying them more of stuff that already costs our society too much to produce. Meanwhile, centrists are trying hard to kill the one provision in the bill that actually addresses excessive health care costs — allowing Medicare to negotiate lower prices for prescription drugs.

If it’s a choice between Cost Disease Socialism programs and doing absolutely nothing to ease the lives of the poor and the working class, then I will pick Cost Disease Socialism every time. But this is not the choice we face. We have alternatives, like Biden’s child tax allowance, that would fight poverty and deprivation in a far more effective way — by giving people cash, and letting them decide what to spend it on (We could do the same thing for retirees, by the way). We have ideas like Medicare price negotiation that could actually decrease the social costs of the overpriced services. And we have ideas like the Clean Energy Performance Program, infrastructure investment, and research funding that would make things like energy and transportation cheaper, increasing Americans’ purchasing power and giving them more money to spend on whatever they choose.

This alternative — using the government to increase material abundance — is what Ezra Klein calls “Supply-Side Progressivism” (and what my PhD advisor Miles Kimball calls “Supply-Side Liberalism”). Combining that with cash benefits would create a new kind of progressive economic program — one that doesn’t simply kick out instinctively at problems by flinging more government money at overpriced stuff, but aims to craft an economy that is both efficient and equitable. Taken to an absurd extreme, it’s the question of whether we want the bright, abundant future of Star Trek or whether we want the paper-pushing dystopia of the movie Brazil.

Supply-Side Progressivism is the kind of vision I want to fight for. Cost Disease Socialism is the kind of last-ditch palliative that I will accept, but only glumly. Progressive leaders need to think carefully about the distinction between these two visions of a just society, and focus on embracing the former while minimizing the latter. Otherwise, American society will simply sink deeper into the mire of overpriced bloated low-quality wasteful service-sector hell.

One big source of regulation-induced cost: Excess credential requirements.

For example, in the UK, people can start med school in undergrad.

That shaves of years and many thousands from the cost of an education -> more doctors -> you don't have to pay them as much -> lower costs.

This credentialism is ensured by the established doctor cartel (AMA.)

Similar problem with pharmacists.

In general when looking for more costly regs, I'd look at why Silicon Valley has basically not been able to break into the space and make it more efficient, like it's done in other sectors. And I know you quickly run into licensing rules, but I'm sure there are other reasons as well.

The problem with "negotiating" for more efficient parts of the BBB plan is that the obstructionists (Manchin and Sinema are not representing any honest "centrist" positions) are mostly not doing it out of policy or political goals, but out of corruption. Sinema has gotten a substantial amount of money from the pharmaceutical industry and that is presumably underlying her opposition to price negotiations. Manchin and his family get a lot of income from the coal business and that's why he opposes clean energy initiatives, which must stop coal use first and foremost. The only obstruction which seems honest is Manchin's demand for tight means testing on child credits, which is probably good politics in super-conservative West Virginia.

I don't see any way to "negotiate" with that other than counter-corruption, which isn't really available to the Dems. Manchin could possibly be bought off with a "clean coal" boondoggle with enough plausible deniability but there's nothing the Dems can do to buy off Sinema. Since she's not already wealthy like Manchin and his family they can't offer a boondoggle to benefit her business and they can't give her or her campaign money directly. She could get many times as much money being a darling of the grassroots left, but she apparently isn't bright enough to realize that.