Barack Obama was a successful President

He dealt effectively with the problems of his day, even if he didn't manage to address the problems of the future.

Among conservatives, it’s an article of faith that Barack Obama was a terrible President. But who cares — of course they’re going to say that. What’s more interesting is many progressives — not just leftists, but also mainstream liberals — also regard Obama’s presidency as a failure.

To me, this is a case study in how expectations get over-inflated. In 2008, when I was a grad student attending Obama rallies, the atmosphere was electric. Stadiums were packed. Everyone had a T-shirt and a sign. In the lines outside, everyone was talking about how Obama Was Going To Change Everything.

I was pretty enthusiastic about Obama — I had the T-shirt and the sign too — but I remember thinking at the time that a lot of these people were bound to be disappointed. The fact that Obama was the first explicitly progressive President since at least Carter (and really since LBJ) didn’t mean that our economy was going to be transformed. And the fact that Obama was Black didn’t mean that racism was over in America. But I indulged the effusiveness, because I thought hope was always a good thing to have.

Now I’m wondering whether the inflated expectations of 2008 helped contribute to an overly pessimistic appraisal of Obama’s legacy more than a decade later. No, our economy was not fundamentally transformed, nor racial equality achieved. But as President, Obama really did produce an unusual string of accomplishments. He may not have justified the “hope”, but he really did bring some “change”.

The ARRA and the recovery from the Great Recession

Obama was dealt a very difficult hand coming into the presidency, for two reasons. First, we were in the middle of a financial crisis, and heading into the start of the biggest economic downturn since the Great Depression. Secondly, we were in the era of the unrestrained filibuster, which makes legislation much harder to pass than in FDR’s day even with a congressional majority.

But nevertheless, Obama came into office determined to do his best FDR impression. To be fair, George W. Bush and the Fed had already cooperated to halt the financial crisis with a series of bank bailouts and emergency lending programs. But Bush had been hesitant to go for big fiscal stimulus. Obama was not. As a percentage of GDP, the fiscal stimulus plan he passed through a reluctant Congress in 2009 was bigger than anything other rich countries were doling out:

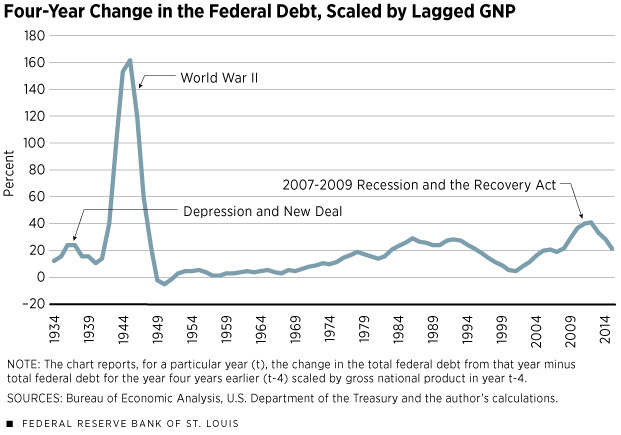

Compared to the entire New Deal, the spending was not as large. But in terms of how much money it borrowed, Obama’s stimulus went beyond the New Deal:

How effective was this spending? Economic estimates of the effect of fiscal programs are always hard to gauge, since they depend on assumptions. But most researchers who looked into the matter concluded that the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act saved millions of jobs, with the infrastructure construction and green investment portions of the bill being particularly effective.

It’s certainly undeniable that the Great Recession ended up being much less painful than the Great Depression, despite being precipitated by financial shocks of approximately equal severity. Unemployment reached 25% in 1933, while unemployment and underemployment combined hit only 17% in 2009-10. And it took us only 6 or 7 years to recover from the drop in per capita GDP inflicted by the 2008 crash, while it took 11 years to recover from the Great Depression.

Of course, a lot of the credit also goes to the Federal Reserve here. But Obama’s bold fiscal action was part of the reason we got a lost half-decade instead of a lost decade. By 2014, the engine of American growth was humming again — and unlike in previous expansions, this time more of the fruits of that growth were going to the people at the bottom of the income distribution.

The ARRA also left behind positive long-term economic legacies that outlasted its recession-fighting effects. The spending fixed a lot of our creaking infrastructure. And its support for the solar and wind industries helped make those technologies cheaper, pushing them down the learning curve and paving the way for the cheap green energy revolution of the 2020s.

There have been three big criticisms of Obama’s recession recovery efforts. First, people allege that the stimulus was too small. Second, many complain that Obama failed to help homeowners enough, allowing massive middle-class wealth destruction. And some believe that Obama wasn’t tough enough on the culprits of the 2008 financial crisis, letting too many bank execs and managers stay in their jobs even after their institutions were bailed out.

I generally agree with these criticisms. Obama could have done better (at least, with a willing Congress). But the same is true of LBJ, FDR, or any successful progressive President in our history. The fact is, Obama’s stimulus had a big positive effect, it was significantly bigger than equivalent efforts in Europe, and it was bigger than anything George W. Bush or John McCain or Hillary Clinton would have done.

Obamacare

But Obama didn’t stop with recession-fighting; like FDR before him, he resolved to use a moment of crisis to make long-term progressive transformations to the way the U.S. economy worked. And one of the biggest problems with our economy was our health care system, which by 2009 was clearly failing us.

Obamacare was meant to be a compromise between national health insurance and the quasi-privatized patchwork mess of America’s existing system. It took its inspiration loosely from the so-called Bismarck Model of health care, where health care is universal but can be provided through either public or private insurers, and more directly from Mitt Romney’s health insurance reform when he was governor of Massachusetts. The main goal of Obamacare was to reduce the number of Americans without health insurance, and it succeeded in this goal:

The reform was not incredibly popular when it was first enacted, but gained popularity in the years after it went into effect:

Now, Obamacare is not a smashing success. It largely failed to restrain the upward trajectory of health care costs; in my opinion, high costs are our system’s biggest problem because they make it politically and economically difficult to increase spending or broaden coverage. A public option, which was dropped from the bill, would have given the government expanded leverage to negotiate down our anomalously high prices. And the Obamacare system did leave 10-11% of Americans uninsured.

But Obamacare is still a landmark achievement. It’s the most significant and sweeping health care reform since Medicaid in 1965. And with the complete failure of Bernie Sanders’ push for nationalized health care, Obamacare is also the most significant and sweeping health care reform we’re likely to see in the current political era.

And despite claims that Obama preemptively compromised away his leverage in a doomed effort at bipartisanship, Obamacare’s passage was a very close-run thing; the recent failure of the Build Back Better bill, and its replacement with the more targeted Inflation Reduction Act, should demonstrate that the ideological diversity in the Democratic party makes truly bold progressive legislation very difficult. FDR’s experience with the cancellation of his “Third New Deal” programs by Southern Democrats is another parallel here.

Dodd-Frank

One of these was the Dodd-Frank financial regulation bill. After the crisis of 2008 it was clear that finance needed to be reined in once again. Dodd-Frank, enacted in 2010, was a sweeping bill that transformed financial regulation in the United States. It created new government agencies — the Financial Stability and Oversight Council, the Orderly Liquidity Authority, the Office of Financial Research, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. It endowed the Fed and the FDIC with new regulatory powers. And it created the Volcker Rule, which bans many kinds of proprietary trading by systemically important banks.

All of these measures were aimed at curbing the excesses of the pre-2008 financial system, and making sure that a similar crisis doesn’t happen again. Normally, it’s hard to evaluate the success of such restrictions, because crises that don’t happen are the proverbial “dog that didn’t bark” — if you wash your hands every day and don’t get sick, should you keep washing your hands, or stop? Etc. etc. The financial sector definitely seems to have calmed down and become less excessive since 2008, but this could also be due to the chastening effects of the crisis itself.

But in the case of Dodd-Frank, we can say a little bit more, because only a decade after the act’s passage we got the Covid shock. Yes, emergency lending programs kept the economy afloat, but there was no giant wave of defaults on bank loans even after the emergency programs ended. There was no overhang of toxic assets on bank balance sheets, whose uncertain value kept banks from lending and kept counterparties from knowing whether banks were solvent.

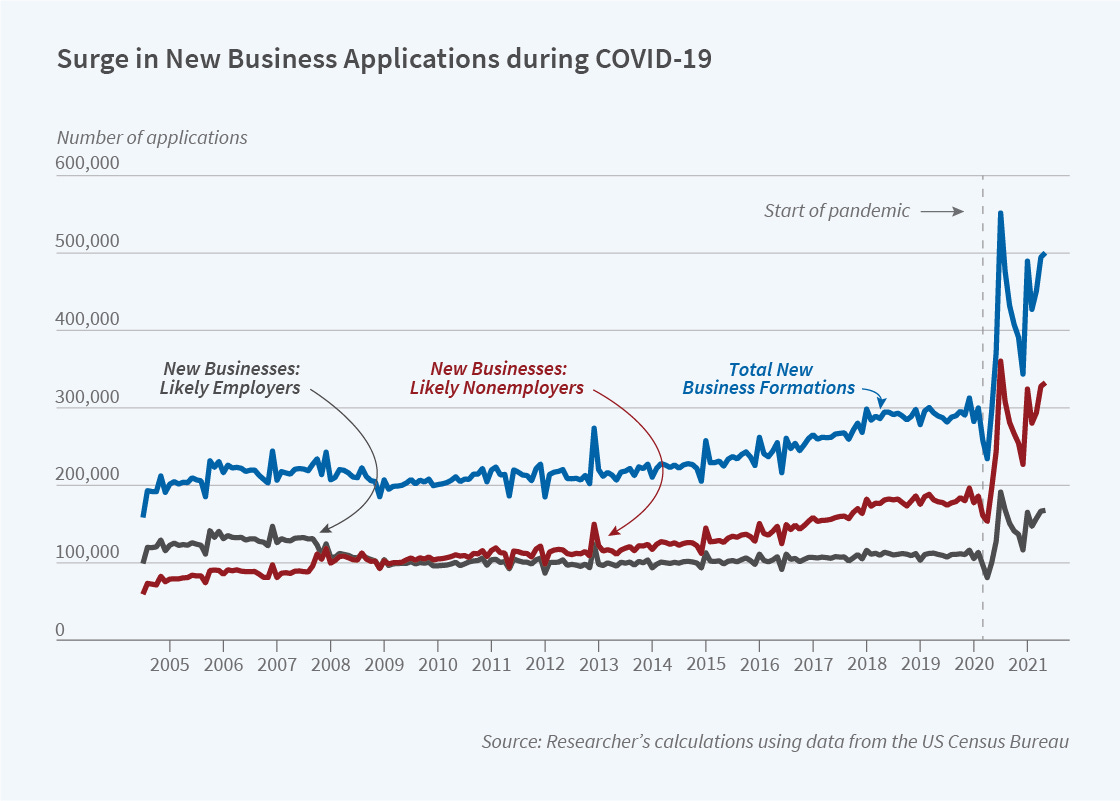

Meanwhile, banks are lending and business is booming. There was great fear that Dodd-Frank would lead to a decline in business formation, which had already been anemic for years. But new business formation started actually trending up after Dodd-Frank came into effect. And it spiked in the pandemic and has remained high since then:

Meanwhile, mortgage lending is robust and there has been another homeownership boom, but this time to borrowers with better credit than in the 2000s.

So the banking sector seems to be more robust, and it seems to be doing its job. I’d call that a win for Dodd-Frank and for Obama — and one that very few people talk about these days. Just like in the Depression, reining in an out-of-control finance sector seems to have had long-lasting salutary effects.

After the Tea Party: the Clean Power Plan and DACA

No President can do very much without the cooperation of Congress. FDR was stymied by a conservative Congress in the late 1930s, while Reagan was frustrated by Congressional Democrats. In 2010 the Tea Party Congress roared into power and made further big legislation impossible during Obama’s final 6 years in power. Obama was forced to fall back on executive-branch regulatory authority to make further policy changes, and this is simply much less powerful than Congressional legislation (as it should be).

But even so, Obama managed to get some important things done. There is a piece of un-passed legislation called the DREAM Act, that would shield from deportation anyone who was brought to America illegally as a child. This is an extremely popular idea, but nativists consistently manage to block the legislation in Congress. So in 2012, Obama used his regulatory authority to create the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, basically refusing to deport anyone who would be protected by the DREAM Act if it passed. This protected hundreds of thousands of people from undeserved deportation.

In his second term, Obama also implemented the Clean Power Plan, which used regulatory authority to order states to reduce carbon emissions by whatever means they chose. The plan was canceled by Trump after just a couple of years, so it didn’t have a chance to make a big short-term impact on carbon emissions. But it probably did spur states to start taking a harder look at solar and wind power, which had come down in price enormously in the years before the plan was released. And it seems plausible that that nudge helped accelerate us toward the renewable transition that is now gathering force.

DACA and the Clean Power Plan were modest but real (and in my opinion, positive) achievements.

Domestic successes, foreign failures

On domestic policy, the combination of the ARRA, Obamacare, and Dodd-Frank represent greater policy accomplishments — and more progressive accomplishments — than any Democratic President since LBJ. They were done in 2 years, which is a lot faster than LBJ or FDR accomplished their reforms. And they were accomplished in the face of a difficult institutional environment, where the unrestrained filibuster makes it nearly impossible to pass truly bold legislation with a simple majority.

Overall, Obama effectively addressed the severe domestic policy challenges he inherited from the previous administration. He restrained the financial sector and cleaned up the damage it had done to the economy, restoring us to robust growth. And at the same time, he managed to make long-term headway on the hard problem of healthcare, while also using regulatory authority to effect minor progress on immigration and climate change.

I call that a major success on domestic policy. People who think Obama’s domestic record represents a failure are simply experiencing the letdown from their own impossibly high expectations.

On foreign policy, however, Obama’s record is more mixed. On the War on Terror, Obama was mostly successful — he killed bin Laden, extricated the U.S. from the pointless peacekeeping operation in Iraq, and drew down most of our presence in Afghanistan. He handled the emergence of ISIS effectively as well, leading to its relatively swift defeat. As a result, the War on Terror was effectively concluded, though of course terrorism as a military tactic will remain and Islamic fundamentalist regimes like the Taliban will not entirely vanish from the Earth.

On the Arab Spring and the wars that followed, Obama’s record is more mixed, but I’m not convinced there’s much more he could have done. U.S. appetite for further military adventures in the Middle East was nil. Obama gets criticized fairly equally for failing to intervene more in Syria and for intervening too much in Libya. So I don’t agree that this represents a dramatic failure for Obama, even though it was hardly a success either.

But it turns out that both the War on Terror and the Arab Spring were largely distractions from the true looming foreign policy threat — the reemergence of great-power conflict. Obama’s weak response to Russia’s seizure of Ukrainian territory ultimately ended up encouraging Putin’s further adventurism and leading to the current catastrophic war. In Asia, Obama refused to acknowledge the importance of Xi Jinping’s accession to power and the country’s concomitant aggressive, nationalistic turn. He remained overly enamored with the failed Clintonian idea that engagement would make China more progressive, and his “pivot to Asia” was too little, too late. Obama might possibly have used the exigency of the Great Recession to revive U.S. industrial policy and start competing effectively with China in high-tech manufacturing, but — apart from a few minor, halting efforts — he didn’t even really try.

He was so occupied with fighting the problems of the present that he wasn’t able to concentrate on the problems of the future. And so now we find ourselves racing to catch up.

But as I see it, the verdict on Obama on domestic policy has to be that he made great headway on the problems he inherited from Bush — a devastated financial sector, a collapsing economy, a large number of uninsured people, and a still-scary Islamist threat. He was a crisis President, and he beat back the crisis. The bitterness and regret that many progressives now feel toward his administration is a function of their own inflated expectations going in.

I agree with your assessment.

I believe one of Obama's most unheralded accomplishments is to retain much of the financial team and policy put in place by Bush. A different president might have taken a very different line of attack. It's true that bankers were not held to account, but maybe that was the wise price to pay for keeping the banking system intact.

Understandably, it is much harder to give credit for disasters averted. But Obama deserves it.

While Obama was a successful President, I think he failed badly on two fronts.

He was too much of a Wall Street President, overly committed to preserving the structure of the financialized economy we have rather than tearing more of it down and holding the bad actors accountable for the GFC. So, unlike some people in your list of commenters, I believe he squandered a historic opportunity to blow up Wall Street - commercial banks, investment banks, investment partnerships, the carried interest loophole, privileging capital over labour income, etc. etc. His primary error was putting a committed institutionalist like Tim Geithner in the Treasury rather than Paul Volcker (or Elizabeth Warren!), who knew the banks and funds for the grift machines that they are and would likely have lit the regulatory and structural equivalent of an atomic weapon on Wall Street.

His second major error, and an unpardonable one, IMHO, is Syria and Libya. Syria was probably an unforced error, and a legacy of the unholy mess that the Bush and the second Iraq war had wrought upon the region. Obama and many liberal Democrats (and probably many neoCons) also irresponsibly promoted the Arab Spring-like movements in the Arab world, most of which had no chance of success without forceful intervention by the West. And, of course, we saw how THAT worked in Libya, for which, despite his “lead from behind” line, he does bear an large portion of the blame. Obama had a shot at leaving well enough alone, but did not resist his advisors or his own impulses enough. In the Middle East, the opposite of secular authoritarianism is mostly illiberal theocracy, not liberal democracy. The US State Dept does not seem to realize this, and Obama allowed his idealism to trump what should have been common knowledge.

For all that, I voted for him twice. And would have done so again if he had been allowed to run for a third term.