Authoritarians are not governing effectively

Boots are stamping on faces, but the trains are not running on time.

A week ago, I wrote that the supporters of liberal democracy need to offer the world a concrete vision of the kind of future they want to create. But even though this vision hasn’t yet emerged, the authoritarians of the world are already making a pretty good case for liberal democracy simply by being incredibly incompetent.

The selling point of authoritarian rule has always been that dictators, oligarchs, and strongmen are competent and purposeful — that democracies dither while authoritarians act. When people tell you that “Mussolini made the trains run on time”, this is what they mean.

I’m not prepared to render a verdict on whether and when democracies or autocracies are more effective at governance (there is a very long academic literature on this, but few solid conclusions). I would certainly never claim that only democracies can govern effectively — Park Chung-hee, Deng Xiaoping, and Lee Kuan Yew certainly put that notion to rest. But I want to push back on the notion of authoritarian effectiveness in two concrete ways.

First, I’d like to note that much of the notion of authoritarian competence is built on simple myth-making. Mussolini actually didn’t make the trains run on time — he just built some big fancy train stations, while the trains still ran late. And this is actually very typical, because dictators lie constantly. In a recent paper, Luis Martinez looked at satellite data on night lights — a proxy for economic activity — and found that authoritarian countries (as measured by Freedom House’s rankings) tend to have a much bigger discrepancy between reported GDP figures and observed light output. The Economist has an excellent writeup on this paper, so I’ll just repost one of their beautiful graphs:

In other words, democracies tend to be pretty truthful in their economic statistics, while authoritarian countries tend to vastly overstate their economic performance.

Martinez finds that one of the worst offenders is China. By official statistics, China’s GDP almost quintupled over the last two decades; Martinez, using satellite data, estimates that it less than tripled. Even if the reality is somewhere in between, it implies that China’s growth, while undeniably impressive, is less of a singular achievement than many believe. Martinez finds that India’s growth, in contrast, has been only modestly exaggerated. This puts somewhat of a damper on the common trope that China’s autocracy allowed it to race ahead of India’s democracy.

Fraud is one reason to doubt the legend of authoritarian competence. Another is the simple evidence of our eyes. The last two decades have seen a resurgence of dictatorial, authoritarian, and even totalitarian governance around the world, with some of the new regimes emerging via “populist” movements in democratic countries. I’ve taken to calling these leaders “Mussolinoids”, since they all seem to share a tendency to thump their chests and promise a return to past greatness. Vladimir Putin certainly fits this mold, as do Xi Jinping and Donald Trump.

But like their Italian fascist predecessor, the Mussolinoids of the 2020s don’t seem to be able to match their rhetoric with substance. They’re simply not making the trains run on time.

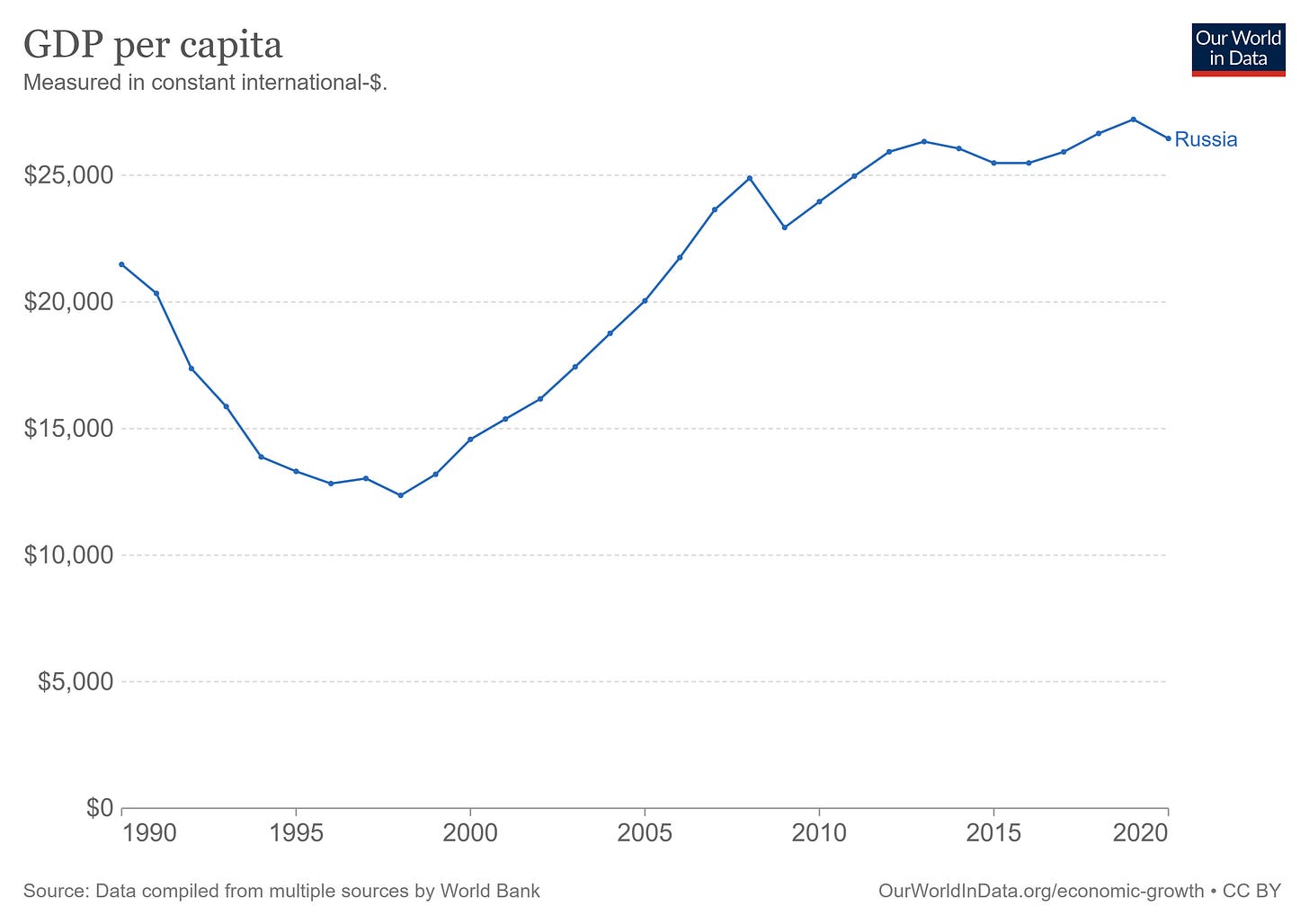

Take Putin, for instance. For the first decade and a half of his rule, he was seen as a successful leader, pulling Russia up from the abyss of post-Soviet economic chaos. and Russia’s living standards certainly grew, at least up until 2008:

In retrospect, though, much of this was due to a historic one-off rise in oil prices. When that ended, so did Russia’s growth. Some of the flatlining since 2008 has been due to the sanctions that the U.S. levied on Russia after Putin started the Ukraine war in 2014, but…well, that was Putin’s decision too.

And more generally, turning yourself into a petrostate is just a bad strategy of national development — the same mistake the USSR made in the 70s. But whereas the USSR made a mighty effort to stay self-sufficient in industrial goods, and mostly succeeded, Putin’s Russia exported oil and imported the technological goods — machine tools, mining equipment, computer chips, etc. — that it needed. This came back to bite Putin severely when even tougher sanctions were levied when he invaded Ukraine this year; unable to buy parts and machinery from Europe and the U.S., Russia is finding it very difficult to replace the materiel it’s losing on the battlefield.

But the incompetence of Putin’s regime goes far beyond import dependence and ill-advised wars. The recently announce military mobilization — which was supposed to intimidate Ukraine and the West into making territorial concessions — has been an absolute debacle. Every day we see videos and stories like this:

And the “mobiks”, as these hapless cannon fodder are called, have utterly failed to make a difference on the battlefield, where Ukrainian victories continue apace.

Putin’s military, administrative, technological and industrial incompetence stand in stark contrast to the Soviet Union. The USSR lost its share of wars (to Poland in 1918-21, Afghanistan in the 1970s, and arguably Finland in 1939-40), but it’s hard to deny that the Red Army was a far more fearsome force than what Putin is fielding now. The USSR wasn’t very efficient at manufacturing, but it could make its own machine tools. And it’s hard to imagine Putin’s Russia inventing space launch and space travel technology. The old Communist Party far from a model of competence, but compared to Putin’s regime they were a smoothly oiled machine.

Xi Jinping, unlike Putin, took over a country at the apex of its growth and effectiveness. Even if its GDP is somewhat overstated, China under Deng and his hand-picked successors Jiang and Hu achieved one of the world’s great growth stories, turning what had been a dysfunctional backwater into the center of global manufacturing in just two generations. Xi was undeniably expert at taming this system to his will. In fact, he’s expected to be confirmed for a third term during the CCP’s party congress next month, making him the most powerful leader since Mao.

But as soon as Xi got in the driver’s seat, he started screwing up. During his tenure, China’s growth steadily slowed from its former dizzying heights to a modest 6% or so, and has slowed far more during the current recession. Xi’s major initiatives, like the Made in China 2025 industrial policy push, may have onshored some strategic supply chains, but they have notably failed to restore growth. China is industrialized but still a middle-income country, so this means that it’s no longer on course to catch up with the developed world.

Xi’s first big blunder was the Belt and Road project. Conceived as a way of providing work for Chinese contractors while building Chinese geopolitical influence abroad, the global mega-project has basically failed to create economically viable infrastructure anywhere. Now host countries are getting mad as debt mounts, investment doesn’t pay off, and Chinese workers and companies take over from locals.

But this was only one of a long litany of Xi’s screwups. His pointless crackdowns on IT companies had a chilling effect on entrepreneurship and investment. His decision to let the real estate industry crash after the failure of Evergrande helped plunge the country into a recession, while his insistence on a permanent Zero Covid policy (and refusal of Western vaccines) sealed the deal. Meanwhile, Xi’s aggressive “wolf warrior” diplomacy and crushing of dissent in Hong Kong and Xinjiang have merely turned much of the world against China. Now the CCP leadership is flailing around, unsure of where to go or what to do next, even as Xi continues to focus on cementing his absolute power and spreading his personality cult.

I’m happy to say that I managed to predict Xi’s fundamental lack of governing competence a year before it started to become conventional wisdom — not through any deep knowledge of China, but simply by recognizing a chest-thumping Mussolinoid when I saw one. Now, in the wake of a recession that has tarnished Xi’s brand somewhat, more people with deeper knowledge of China’s system are feeling free to speak up.

Anyway, that brings us to the third major modern Mussolinoid — Donald Trump. Our democratic system fortunately prevented him from overthrowing democracy and seizing power in 2020 (though he will try again in 2024). But organizations like Freedom House have no illusions about his authoritarian tendencies.

And like his fellow Mussolinoids overseas, Trump was less than effective in restoring past glory. After vowing to restore U.S. manufacturing that had been offshored, Trump failed to jawbone companies into no longer shipping jobs overseas, championed a giant electronics factory in rural Wisconsin that never materialized, passed a corporate tax reform that probably encourages offshoring more than the old tax system did, and started a trade war that notably failed to generate much if any reshoring. The one very effective thing Trump did do during his time in office was Operation Warp Speed, in which he luckily decided to leave the task to civil servants and the military.

Fortunately the U.S. booted Trump in a way that Russia and China haven’t been able to eject their own Mussolinoids. But some Republicans are trying to continue Trump’s ideological legacy with something called “national conservatism.” This ideological project, which takes many of its cues from Hungary’s Mussolinoid leader Viktor Orbán, combines traditional Republican culture wars with an admiration for authoritarian rule, which they see as necessary to save America and the world from the terror of wokeness.

But when it comes to their plans for actually governing the nation, the natcons’ ideas are simply disasters waiting to happen. Their strongest idea is to cut off immigration, which dovetails with their desire to slow or reverse demographic change. But immigrants are the lifeblood of the American economy, especially of the high-tech industries that keep us a step ahead of rivals like China. Meanwhile, natcons rhetorically attack universities as hotbeds of wokeness, ignoring their crucial role as the drivers of scientific research. And natcons want to defend the suburbs as a way of life, defying the need for greater density and the fiscal unsustainability of the infrastructure that supports sprawl.

In other words, America’s own authoritarians want to use economic policy primarily as a tool to prosecute culture wars, which are what they really care about. The result, if they ever get their way, is incredibly predictable — more of the dysfunction and stagnation that have plagued Putin’s Russia, Xi’s China, and other nations unlucky or foolish enough to come under the sway of Mussolinoid leaders.

In other words, whether or not authoritarianism can govern competently in the abstract, it clearly seems to be failing in the concrete here-and-now of the 2020s. In country after country, authoritarian leaders have focused on internal conflicts and quarrels with neighbors rather than the hard work of nation-building. The USSR, Deng Xiaoping’s China, and other authoritarians of the 20th century committed plenty of atrocities, but at least some of them also created strong institutions and produced economic growth, technological progress, and military strength; the authoritarians of the 21st century are simply temper tantrums made flesh. It’s easier to throw a temper tantrum than to build a nation — easier to simply stamp your boot on a human face without actually making the trains run on time. But there’s just no future in it.

Mussolinoids is a brillaint term as it reminds me of something similar that only leads to backside pain and discomfort. Another wonderful post and most of all, unlike a lot of writing, you often stake a claim not commonly asserted and defend it with evidence and observation.

Have you read Dan Slater's "Ordering Power," about Southeast Asian authoritarian governments?

Slater argues that authoritarians delivered economic growth, when they did, because their supporting elites were nervous about revolution and foreign invasion.

That is, authoritarians delivered growth because growth was the best hope of security.

Jobs and land reform kept the masses compliant; foreign exchange and/or heavy industry made the military strong. (Park's Korea, Deng's China.)

Conversely, where elites were less afraid of invasion and/or revolutionaries, authoritarians delivered "security" by the easy routes of stagnation and crony perquisites, not growth. (Philippines, or arguably today's China.)

It's not a perfect theory. Mussolini certainly thought he was there to deliver a strong army and keep the leftists down, but he didn't give Italy an economic miracle. Conversely, Erdogan and Modi started out genuinely delivering economic growth, albeit back when they were less politically invincible and less authoritarian.

But up to a point, I like the idea: authoritarians focus on "security," and "security" only means growth when the alternative is imminent revolution or invasion.

More often, the feeling of security is the reality of stagnation. Which is one reason why authoritarians promise to save the country, and end up stalling it.