At least five interesting things: The new conservative era (#53)

Conservative poll shift; Democratic machine politics; science and politics; some good news; better teachers; the AI slowdown; consumer confidence

It feels like a new era out there in America. Not quite like the 80s, but Trump’s election seems to have been a psychological turning point, not toward traditional conservatism, but definitely toward some sort of new syncretic right-wing politics. Figuring out what that means for the nation will take years; right now, we’re still mostly just in the mode of verifying that it’s happening, and asking where progressives and Democrats messed up.

Anyway, I’ve got several different podcasts for you this week, if you like hearing me talk. I did a fun video debate with Peter St. Onge for ZeroHedge about the wisdom of abolishing the income tax:

I went on Andrew Xu’s podcast and talked a lot about how Trump could affect the economy:

And here’s an episode of Econ 102 where Erik and I talk about special interest nonprofits and the woes of the Democratic party:

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things.

1. The new conservative era

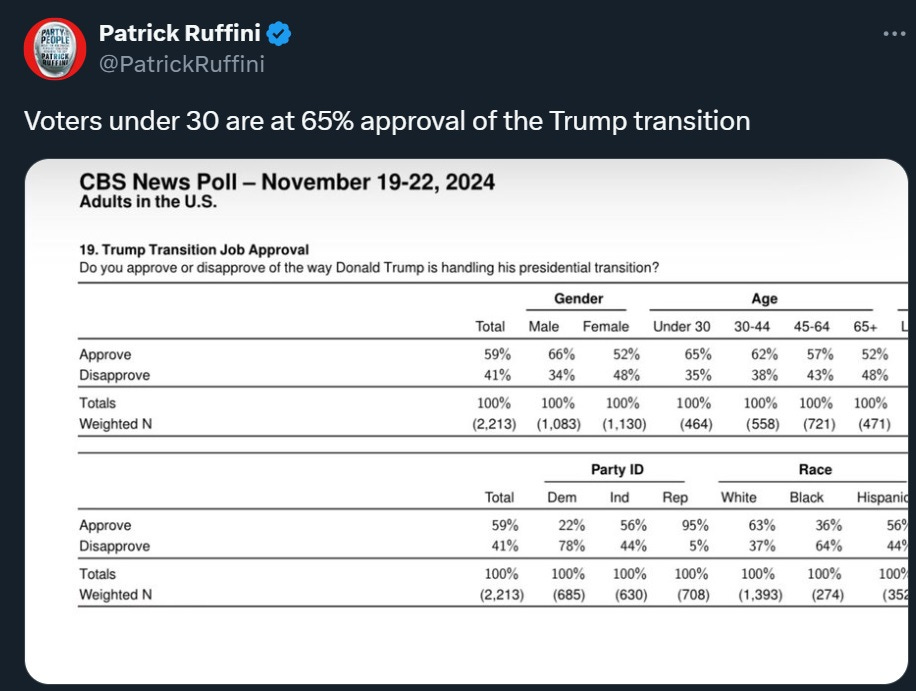

Shifts in public opinion and culture can be astonishingly rapid. The generation that poured out into the street just four years ago to protest against the police after the death of George Floyd now strongly approves of the Donald Trump transition:

In fact, you can see the pro-GOP trend across a huge number of polls; it’s just everywhere. Here’s one more example:

Meanwhile, other polls show voters shifting abruptly rightward on key cultural issues like trans issues.

And if you don’t believe polls, take a look at an electoral map:

Elections are never about just one thing, but “general rejection of progressivism” is probably as good of a simple model of the 2024 election as you’re ever going to get.

The key questions here are “Why did this happen?”, and “Will the shift continue?”. I don’t claim to know the answers to either of these. My guess is that it’s sort of a coordination game — people didn’t really like either the progressivism of the 2010s or MAGA, but when it became clear that more people disliked the former than the latter, the country just sort of collectively concluded that it was time to reject 2010s progressivism. This isn’t quite the same as Timur Kuran’s theory of “preference cascades”, which relies on people pretending to believe things they don’t really believe. But it’s recognizably in the same family of theories. The key here is that the desire to be part of a majority consensus exists alongside underlying policy preferences and ideologies.

2. Democratic party politics is urban machine politics, scaled up

I’m not much of a politics writer, but the 2024 election made me think a little harder about the Democratic party. I’ve been slowly groping toward a general theory of where the Democrats are going wrong, and it goes something like this: Democrats are a stronger, more centralized party than the Republicans. This makes it easier for them to keep extremists and populists from taking control of the party, but it also makes them more susceptible to jawboning by special interests.

A variety of activists and special interests — collectively known as “The Groups” — can basically persuade Democratic staffers and politicians of their ideas in the proverbial smoke-filled rooms, well out of the public eye. Democrats’ focus on identitarianism allows the Groups to falsely present themselves as representatives of various “communities” — the Latino “community”, or the trans “community”, etc. And Democrats’ legacy of urban machine politics causes them to think that these “communities” can basically be bought off with targeted benefits, much as they would be in urban politics. Incidentally, this is probably a big part of why progressive cities are governed so badly. Anyway, when all of this finally has to make contact with the actual voting public on election day, it turns out that The Groups weren’t really representative of easily buy-able “communities”, and voters reject the Dems at the polls.

That’s a very simplified model, of course. But it looks like in the aftermath of the 2024 election, a lot of people are zeroing in on a model like this to explain Democrats’ weakness. Ezra Klein recently interviewed Michael Lind, titling the interview “The End of the Obama Coalition”, and they discussed the problems with the Dems. Here are some excerpts from Ezra’s writeup:

In my post-election essay, I said that the 2024 election marked the end of the Obama coalition…[S]ome of the political strategies the Democrats thought would turn Obama’s 2008 and 2012 coalitions into an enduring generational majority — they’ve failed. Democrats worked damn hard over the past few years to deliver what they thought, what they were told, Black and Hispanic and working-class and union voters wanted.

And instead of solidifying support from those voters, they’re seeing them flee to Donald Trump. But I’m also saying something about the structure of the Democratic Party itself…The Obama era…was a collection of institutions and power bases and elite networks. Michael Lind…has argued that it was kind of a political machine, one built around urban political support, foundations, nonprofits, mass media…

I don’t think what’s next for the Democratic Party is just new ideas or campaign tactics…I think it’s…learning how not to listen so much to its funders and interest groups — and how to listen more to the people it’s been losing.

And here are a few excerpts from Lind’s portions of the interview:

The Obama Democrats, in my view, are the first American national party that is also a national machine in the sense that it’s kind of replicated on the national level the sort of machine structure that has long existed, both in Republican machines and Democratic machines at the state and local level…[B]asically every big city over a million or so people and every college town is 100 percent Democratic all the time — and this is kind of new. So since the population is largely urban now in the United States, to have a national Democratic machine really just means linking up these big-city urban machines and college-town, one-party systems…

[O]ld party structures [have] been so eroded that they have been replaced in these Democratic cities…by nonprofits. Not by think tanks…but by service, delivery nonprofits dealing with homelessness, with education, with other things, which get grants from the city government to carry out functions that were performed before the outsourcing that took place beginning with the Clinton era.

The whole thing is worth reading in full. Klein pushes back strongly on some parts of Lind’s story and agrees with others. But in general both of them agree that the basic diagnosis that I had been groping toward — the Democrats as a scaled-up version of urban special-interest machine politics — is a big part of what’s wrong with the party.

3. Will science start to de-politicize?

I’ve been arguing for quite a while that science and politics don’t mix. The public generally agrees with me on this — research by Alabrese et al. (2024) have shown that when scientists get publicly involved in political arguments, it decreases trust in science as an institution.

Now the tide of opinion may be turning within the scientific establishment itself. Marcia McNutt, president of the National Academy of Sciences, recently wrote an op-ed in Science entitled “Science is neither red nor blue”, arguing for a separation between science and politics. Some excerpts:

Long before the 5 November US presidential election, I had become ever more concerned that science has fallen victim to the same political divisiveness tearing at the seams of American society. This is a tragedy because science is the best—arguably the only—approach humankind has developed to peer into the future, to project the outcomes of various possible decisions using the known laws of the natural world…As the scientific community continues to do so now, it must take a critical look at what responsibility it bears in science becoming politically contentious, and how scientists can rebuild public trust…

For starters, scientists need to better explain the norms and values of science to reinforce the notion…that science, at its most basic, is apolitical…Whether conservative or liberal, citizens ignore the nature of reality at their peril…

Although scientists must never shirk their duty to provide the foundation of evidence that can guide policy decisions and to defend science and scientists from political interference, they must avoid the tendency to imply that science dictates policy. It is up to elected officials to determine policy based on the outcomes desired by their constituents. It is the role of science to inform these decision-makers as to whether those desired outcomes are likely to result from the policies being enacted…

Last month the NAS Council issued a statement reaffirming its core principles of objectivity, independence, and excellence.

The whole op-ed is quite good.

Meanwhile, Laura Helmuth resigned as editor-in-chief of Scientific American. Many have accused Helmuth of steering that venerable publication in a more politicized, progressive-activist direction:

When Scientific American was bad under Helmuth, it was really bad. For example, did you know that "Denial of Evolution Is a Form of White Supremacy"? Or that the normal distribution—a vital and basic statistical concept—is inherently suspect?…Three days after the legendary biologist and author E.O. Wilson died, SciAm published a surreal hit piece about him in which the author lamented "his dangerous ideas on what factors influence human behavior." That author also explained that "the so-called normal distribution of statistics assumes that there are default humans who serve as the standard that the rest of us can be accurately measured against." But the normal distribution doesn't make any such value judgments, and only someone lacking in basic education about stats—someone who definitely shouldn't be writing about the subject for a top magazine—could make such a claim…

Perhaps the most infamous entry in this oeuvre came in September 2021: "Why the Term 'JEDI' Is Problematic for Describing Programs That Promote Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion." That article sternly informed readers that an acronym many of them had likely never heard of in the first place—JEDI, standing for "justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion"—ought to be avoided on social justice grounds. You see, in the Star Wars franchise, the Jedi "are a religious order of intergalactic police-monks, prone to (white) saviorism and toxically masculine approaches to conflict resolution (violent duels with phallic lightsabers, gaslighting by means of "Jedi mind tricks," etc.)[.]"

It’s easy to see how that kind of thing would convince regular Americans that the country’s scientific establishment had rejected objectivity in favor of ideology. Helmuth’s departure is one more small sign that that establishment has realized the magnitude of its public relations problem, and is taking steps to correct the situation.

4. Some positive trends you might not have heard about

I always like to highlight positive trends that are flying under the radar. This week I have two for you. First, deaths from drug overdoses are plummeting:

The New York Times has an article about the possible reasons for the trend, discussing changes in law enforcement and harm reduction programs. Kevin Drum attributes the change to fentanyl simply going out of style. Whatever the reason, it’s great news, though obviously we have a long way to go to get back to 2012 levels.

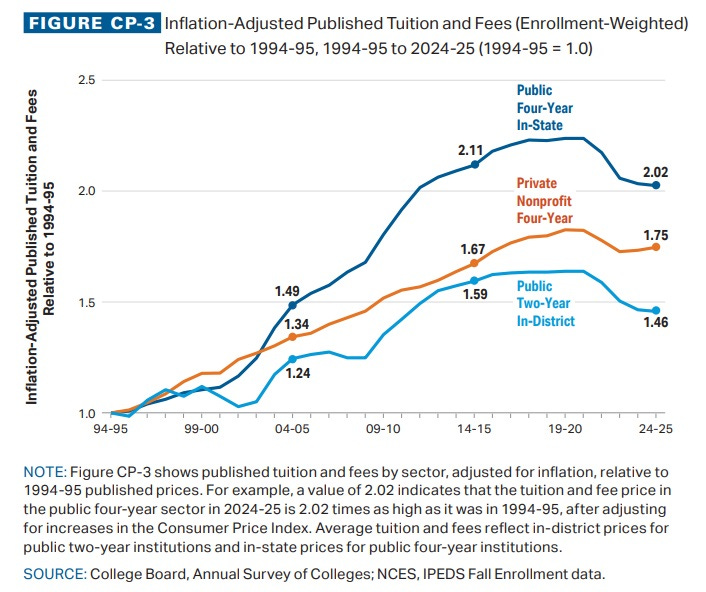

The second positive trend is that college is getting cheaper. Here’s a good Tyler Cowen post on the subject, and here’s a report from the College Board. Key chart:

There is that worrying uptick in the price of private nonprofit four-year schools (this includes the Ivy League). But those schools also give out a ton of need-based financial aid, so the true price that students pay is much less than the published numbers. Here’s another chart:

Anyway, this is great news for the country. Though if you’re an administrator at a university, it may be time to start looking at some headcount reductions.

5. Wanted: better teachers

Here’s a cool paper I missed when it came out. Baron (2020) looks at the effect of a Wisconsin law that allowed school districts to pay teachers for performance, instead of following a fixed salary schedule. As a result — surprise, surprise! — the teaching profession started attracting a higher caliber of worker. Baron writes:

I exploit a shift toward performance pay in Wisconsin induced by the enactment of Act 10, which gave school districts autonomy to redesign their compensation schemes. Following the law, half of Wisconsin school districts eliminated salary schedules and started negotiating pay with individual teachers based on performance…I find that Act 10 led to a 20% increase in teaching degrees. This effect was entirely driven by the state's most selective universities, which suggests that the quality of the prospective teacher pool in Wisconsin increased…I show that the reform increased average test scores on the state's standardized exam by roughly 20% of a standard deviation four years after its implementation.

It shouldn’t be that surprising that incentives work. When you pay teachers more based on performance, you attract teachers who are capable of better performance.

This shows the way forward for education policy in America. Paying teachers much higher salaries, but only if they produce results in terms of better student outcomes, will result in a better-educated American populace. So we should do this everywhere.

The problem is that this obvious strategy runs counter to the demands of a powerful progressive interest group: teacher unions. The unions want to protect the job security of their less competent members, so they block reforms that would penalize bad teachers, even though these reforms would involve paying teachers more money. And the Democratic party, with its machine style of politics, naturally tends to side more with the special interest group here (teacher unions) than with the people who are actually getting served by the industry (America’s youth).

6. More on the AI slowdown

In my last roundup, I noted a bunch of news stories about AI progress possibly slowing down. If you’re interested in keeping track of that story, Timothy B. Lee has a good post about what’s going on:

Some excerpts:

When OpenAI released GPT-4 in March 2023, it helped to cement the conventional wisdom about “scaling laws.” GPT-4 was about 10 times larger than the model that powered the original ChatGPT, and its larger size yielded a significant jump in performance…But 18 months later, OpenAI hasn’t released GPT-5, and CEO Sam Altman says that no model called GPT-5 will come out this year…The story has been similar at other leading AI labs…

AI companies got a one-time boost when they were able to scrape all of the text on the Internet and use that to train models. But if an AI company wants to make transformer-based models that are 10 or 100 times bigger, they are going to need 10 to 100 times as much data…It doesn’t seem like [any available] method will allow the creation of a data set that is as diverse as the Internet but 100 times larger.

It seems like there are possibly two distinct challenges facing the foundational model companies:

There isn’t enough good-quality data to keep scaling up models by orders of magnitude, and

Using more data may not produce gains as dramatic as what we saw in 2022-23.

I think a third problem is that “hallucination” seems fundamental to how LLMs work, which will hold them back from many useful tasks that we might want them to do (such as writing blog posts for us). In any case, the upshot here is that AI innovation will have to discover new ideas going forward, instead of just throwing more data at established ideas.

7. Consumer confidence wasn’t really about interest rates, was it?

Over the last two years, the economy did very well by most conventional measures — low inflation, low unemployment, and so on. But consumer confidence remained low. Though some people blamed “vibes”, there was a theory — promulgated by Larry Summers and other economists, and by some online folks — that high interest rates were weighing heavily on consumers.

New data on consumer sentiment casts a lot of doubt on that theory. The day after Trump was elected, Morning Consult’s high-frequency poll of consumer sentiment shot up, driven by a huge increase among Republicans:

You can see that Democrats’ evaluation of the economy is partisan too, but less so — the Republican jump is about double the size of the Democratic drop.

At this point, if you want to claim that low consumer sentiment during the Biden years was driven by interest rates rather than partisanship, you’ll have to resort to theories about forward-looking expectations, as well as theories about why Republicans and Democrats will be affected differently by a Trump presidency. I’m highly skeptical.

I really hope science will de-politicize. Looking at the new administrations medical appointees I am struggling to see that, but hopefully its a change that keeps sinking in over the next 20 years...

I’m a non-unionized charter school teacher and am appalled by your stance here. It’s so easy for administration to give teachers impossible classrooms that aren’t going to see fantastic results in.

Last year I had one kid with some modest behavioral issues and like my growth and proficiency was great. My colleague had like 7 or 8 of the 10 worst behaved kids in the grade level and oh surprise surprise by any measure her test scores looked worse than mine.

Like I’ve been teaching 15 years and I don’t think I’m terrible but two of those years I’ve had unwinnable messes. I have no data from 19-20 but I’m sure it would have been bad as I spent most of the year physically defending myself and my students from one of their classmates.

I absolutely am against protecting inept teachers from job loss, though I see a lot of this without unions but giving someone a perfect class and giving them a raise because they can deliver great results is disgusting and so is giving someone a terrible class that everyone apologizes for before we even start and saying they deserve less money for harder work.