At least five interesting things: Chaos Blitz edition (#59)

Trump's chaos blitz; Econ data isn't fake; China's tech cluster; Abundance ideas; AI and antitrust; AI in science

For at least the next few weeks, I expect my regular roundups will be dominated by lists of chaotic things that Trump is doing. That’s important to talk about, but I’ll try to keep those sections short and get on to other stuff, because I know it can get old after a while.

Anyway, have some podcasts! I’ve been doing a lot of these lately. Here’s me going on Lev Polyakov’s stream to debate Auron MacIntyre about immigration:

You can also get it as a podcast on Apple Podcasts.

And here’s me having a somewhat silly discussion with Richard Hanania, who has recently sort of converted into a liberal:

And we have two episodes of Econ 102! I did a debate with Nathan Lebenz in which I explained why China is a threat to the U.S.:

And here’s another episode, talking a lot about DOGE:

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things!

1. Trump moves fast and breaks things

In Trump’s first term, lots of people liked to say that his blizzard of inflammatory statements represented a DDoS attack on the media — he just kept saying new things so fast that the media didn’t have time to correct or push back on the previous set.

The second Trump term looks like an institutional version of the same DDoS attack. Trump’s executive orders and public statements, along with the actions of DOGE, are creating chaos almost too fast to keep track of. Here’s a list of chaotic things Trump has done in just the last week:

Trump has halted FEMA grants, meaning that things like equipment for firefighters and security systems for ports won’t get the money they were expecting.

Trump has effectively frozen much of U.S. government science funding, angering universities in red states (and everywhere else), and causing chaos in every field of U.S. scientific research.

Trump ordered the CIA to send him a list of everyone it hired over the past two years. This means the CIA just disclosed the identity of a bunch of its agents, putting them immediately at risk. Whether the Trump administration forced them to make this disclosure publicly isn’t clear.

Trump declared that payments on some U.S. Treasury bonds might have to be halted due to irregularities in the payment systems being examined by DOGE. This would represent a U.S. sovereign default. Markets momentarily freaked out, though they calmed down when Trump’s people walked back his comments.

Trump has paused permitting for solar and other renewables, even on many private lands, leaving many American localities unsure if they’ll be able to get the electricity generation they were planning to build.

Trump has declared his intention to invade and “own” the Gaza Strip, terrifying many Middle Eastern countries.

Trump has abolished the FBI’s Foreign Influence Task Force, which tries to stop foreign powers from meddling in American democracy. He has also abolished a Justice Department task force that goes after Russian oligarchs who evade U.S. sanctions.

And all this has happened in the nine days since I wrote my previous post about Trump’s chaos. That’s a Chaos Blitz!

Now, there are a few points to make here beyond simply gawking in shock and awe at the speed, the scale, and the sheer hubris of the Chaos Blitz. One point is that chaos is not always bad. Occasionally something good can come out of it — for example, I like Trump’s plan to audit California’s high-speed rail debacle, and his decision to review federal funding for NGOs.

But overall, chaos isn’t a good thing. An advanced society runs on predictability and stability, because making decisions in complex environments requires the ability to plan for the future. If firefighters and ports and scientists and doctors don’t know if they’re going to get the government money they were promised, or what regulations they’re going to have to follow, it will paralyze many of them. Much of the machinery of the nation will grind to a halt. In addition to making a lot of people mad, that will probably also result in more inflation.

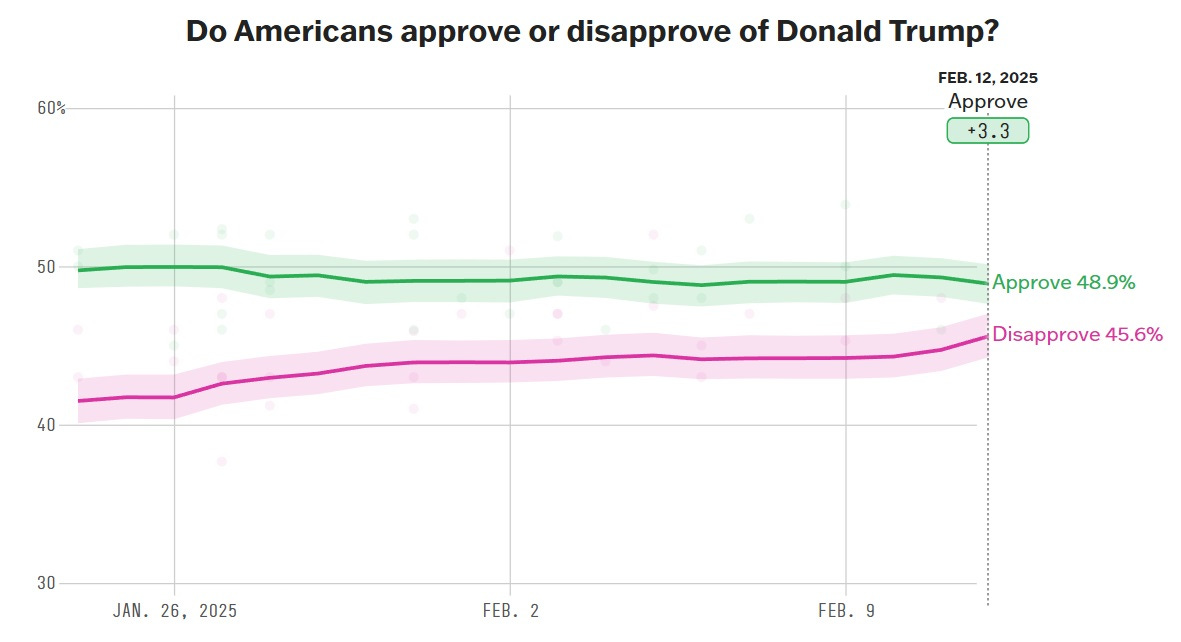

Americans might be starting to wake up to the danger. Trump’s approval has started to tick downward in recent days:

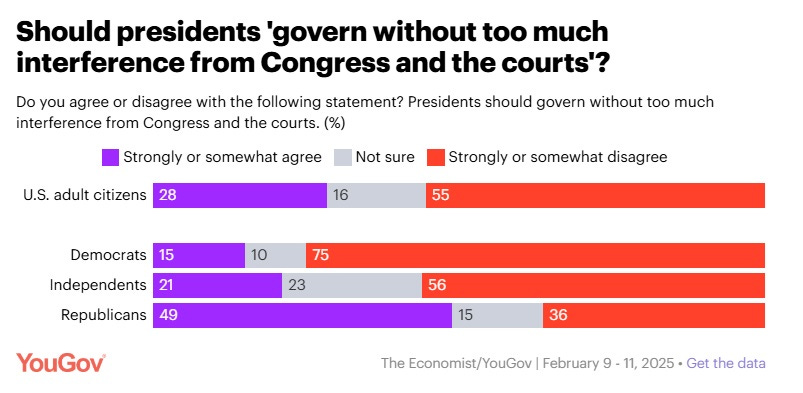

And a YouGov poll suggests that Americans are growing wary of Trump’s adversarial attitude toward the courts:

(Trump may be trying to dial that back a bit.)

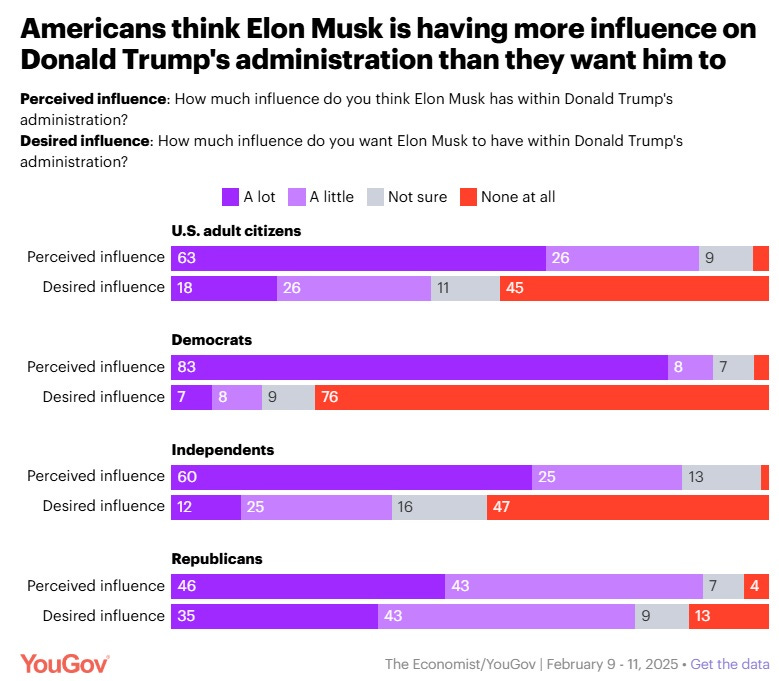

Americans are also not happy with the amount of influence that Elon Musk has within the Trump administration:

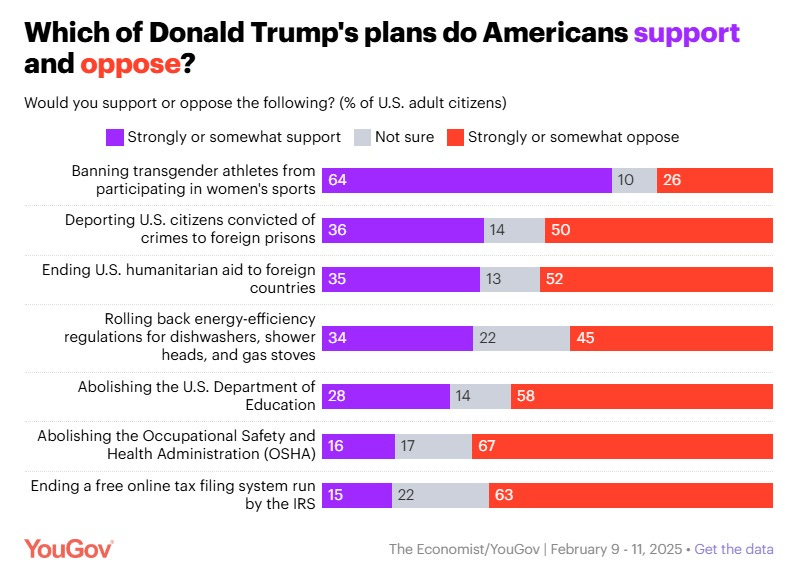

As for Trump’s policies, many of these are unpopular as well:

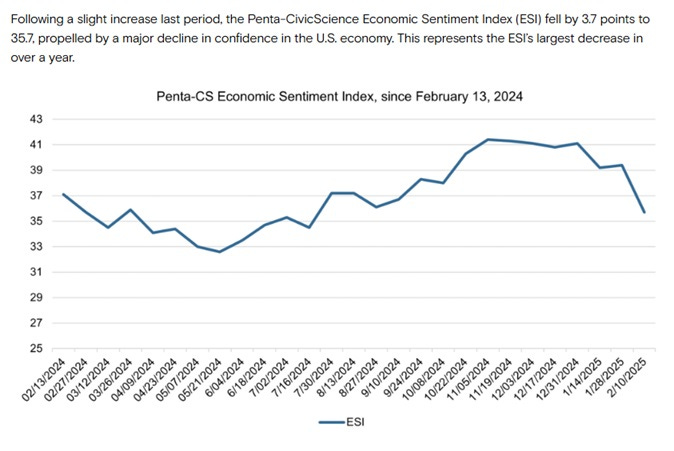

Meanwhile, some data sources also suggest a sudden drop in consumer confidence:

Americans elected Trump to fight inflation, curb the chaos at the border, and maybe fight against wokeness. They did not elect Trump to destroy the federal government, start constitutional crises, or deprive large swathes of America of payments they were expecting to get.

Anyway, we still don’t know how far the Chaos Blitz will go, how long it will last, or how much damage it will ultimately do to U.S. state capacity. But right now, all most Americans can do is sit and hope the storm passes.

2. No, the economic data isn’t fake (sigh)

Every once in a while, someone writes a long screed claiming that the government’s economic data are all wrong, that you’ve been tricked, and that actually the economy is terrible when everyone is telling you it’s good. This inevitably results in a bunch of people who are sort of perma-mad about wokeness or Palestine or whatever yelling “See, I told you so!”, and declaring that actually the economy is horrible after all.

The latest such would-be expose is by Eugene Ludwig, a former U.S. comptroller of the currency.1 But like all other such claims, Ludwig’s are basically specious — U.S. government statisticians are some of the most competent and most honest people you’ll ever find, and they just don’t get lots of big stuff wrong. I was going to write a post dissecting Ludwig’s points one by one, but Jeremy Horpedahl has already written a thread, so I’ll just highlight his excellent work.

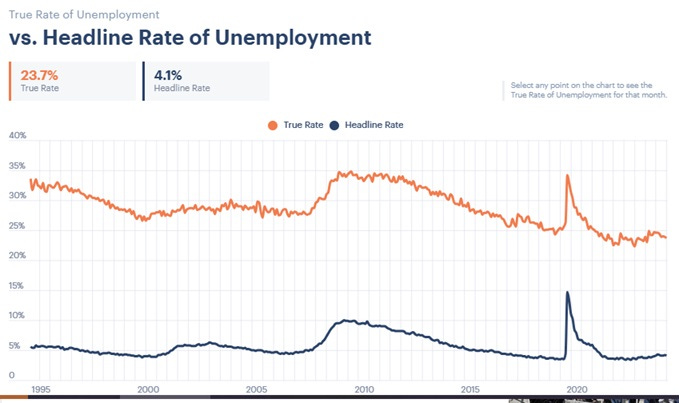

For example, Ludwig writes that unemployment is a lot higher than people think, become some people only work part time and others are poor even though they work:

If you filter the [unemployment rate] to include as unemployed people who can’t find anything but part-time work or who make a poverty wage (roughly $25,000), the percentage is actually 23.7 percent. In other words, nearly one of every four workers is functionally unemployed in America today — hardly something to celebrate.

But Horpedahl points out that even if you use this number as a measure of the so-called “true unemployment”, it was also at historic lows during the Biden years!

Horpedahl also points out that this so-called “true rate” of unemployment isn’t really the true rate at all. It includes people who choose not to work, or who choose to work only part-time, as “unemployed”. And it counts the working poor as “unemployed” for no real justifiable reason.

Ludwig then claims that median earnings are fake, because they don’t include part-time workers:

The picture is similarly misleading when examining the methodology used to track how much Americans are earning. The prevailing government indicator, known colloquially as “weekly earnings,” tracks full-time wages to the exclusion of both the unemployed and those engaged in (typically lower-paid) part-time work. Today, as a result, those keeping track are led to believe that the median wage in the U.S. stands at roughly $61,900. But if you track everyone in the workforce — that is, if you include part-time workers and unemployed job seekers…the median wage is actually little more than $52,300 per year.

But as Horpedahl points out, there’s no government deception involved. The government simply tracks median weekly earnings for full-time workers and for part-time workers separately, instead of lumping them into one measure. In fact, real median wages for part-time workers increased even faster than for full-time workers during the Biden years!

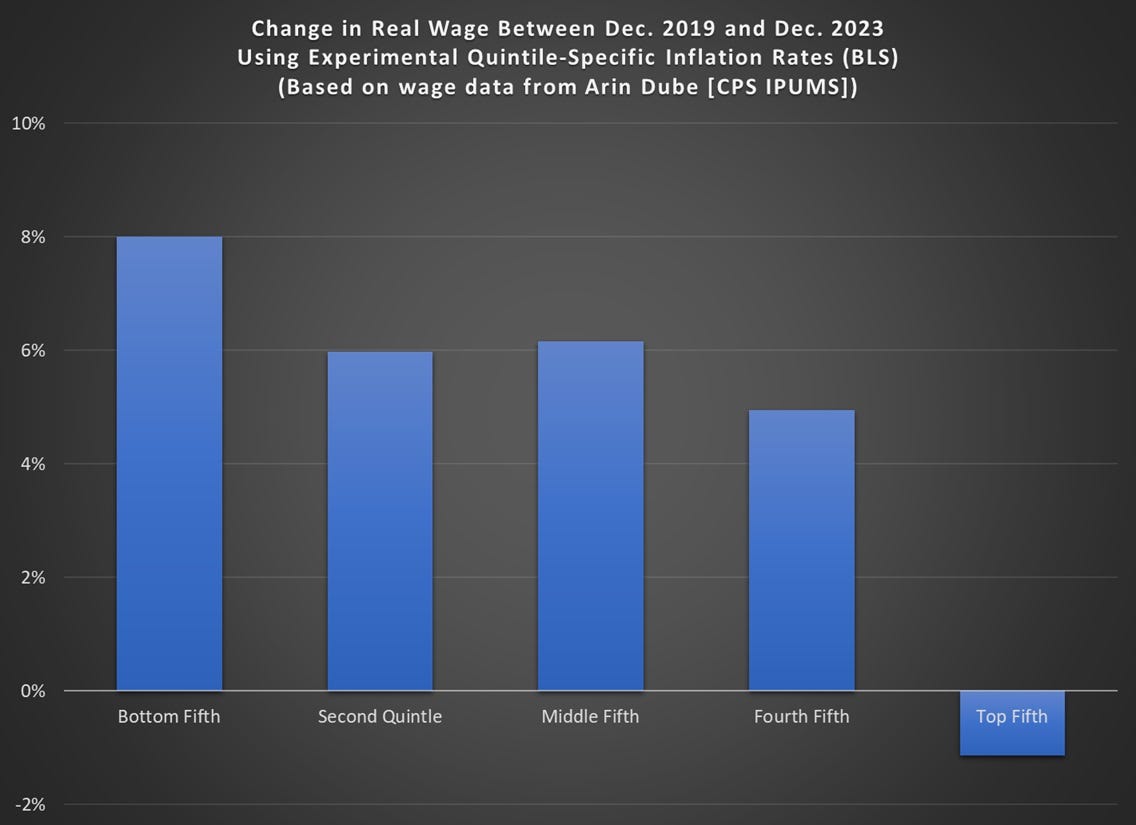

Ludwig also argues that inflation numbers are deceptive, because prices for the things that poor people spend more of their income on (food, rent, gasoline, etc.) increased faster than prices for the things rich people spend more of their income on. That is certainly true. But Ludwig deals with this by creating his own inflation measure that only includes goods that he considers “necessities”.

Horpedahl points out that a much more sensible approach is just to look at inflation rates by income quintile. We actually know how much prices rose for poor Americans and for middle-class Americans — we don’t have to guess! And when we do that, we find that all Americans except for the top fifth saw gains in real wages from 2019 to 2023:

Ludwig’s final complaint is that GDP doesn’t take inequality into account. This is true, but as I wrote back in early 2023, it’s also the case that both wage inequality and wealth inequality have either stopped increasing or gone down since around 2013:

Those trends haven’t really changed in the two years since then. So the story Ludwig is trying to tell here — of GDP growth flowing to the rich but not to the middle-class and poor — is just false for the time period he’s talking about.

So anyway, another post claiming that government economic data is misleading turns out to actually be extremely misleading. I am shocked. Shocked, I tell you!

3. China’s 21st century tech cluster

In recent years, Chinese companies have become extremely competitive in consumer products like electric cars, phones, and drones. At the same time, they’ve also become competitive in various high-value component and machinery products like computer chips, robots, lidar, and batteries. How did they suddenly get good in all of these things at once? One common explanation is that these are the industries Xi Jinping has chosen to subsidize. But Kyle Chan has a different theory — two different theories, actually.

Basically, Kyle thinks the products I listed above form a single cluster of related technologies. This is true in two different senses.

First of all, many of these things help you produce the others. Batteries go into EVs, phones, and drones. So do chips. Industrial robots help make all the other things. And so on. If you have all of the upstream industries in the same country — or, if possible, the same city — then you can very easily become competitive in all of the downstream industries at the same time.2 This gives big countries an advantage over smaller ones — with a larger domestic market, it’s easier to support a greater variety of upstream industries. It’s also very relevant for industrial policy — it teaches us that building a complete local industrial ecosystem can generate positive externalities.

Second, Chan notes that a bunch of these technologies seem to be converging — a car is much less different from a phone than it used to be, in terms of what kinds of components it uses. Basically, both an electric car and a phone are some metal and plastic wrapped around a similar type of battery and some pretty similar types of computer chips. A drone is just that stuff plus a motor. That means if a company has expertise in making one of these products, it’s very easy to start making the others. That’s why Xiaomi was able to spin up an EV arm so fast. And it also means that if a company makes all the downstream products, it’s easy for it to expand into the upstream industries — like BYD becoming a chipmaker.

Anyway, Chan focuses on China’s strengths rather than America’s weaknesses, but it’s easy to see that America will have a lot of trouble competing in this emerging tech cluster. Our conservative leaders oppose EVs and batteries because of culture war madness, while our unions generally oppose automation. This will leave the U.S. with gaping holes in its industrial ecosystem, ultimately hurting the semiconductor, phone, and drone industries as well. Oops.

But also, I think the phenomenon Chan is describing might end up presenting a challenge for China’s companies. He notes that big Chinese companies increasingly make all the same things. That lack of differentiation will cause vicious price competition, resulting in low profit margins. A similar thing happened with Japan’s big manufacturing companies in the bubble years of the 1980s — Panasonic (Matsushita), Sony, Hitachi, Toshiba, Sharp, JVC, Sanyo, and others all made basically the same giant list of electronics, appliances, components, and machinery. Because they competed in every product category, their profit margins stayed low. Similarly, we might see BYD, Xiaomi, Huawei, and a bunch of other big Chinese companies compete each other’s profits away.

4. Ideas for abundance

I continue to believe that the best people working in American politics and policy right now are the abundance folks. While everyone else screams and fights, they’re just quietly working to think of how we could have a country with more stuff for everyone. That’s inspiring!

I just got my review copy of Derek Thompson and Ezra Klein’s book Abundance, which comes out next month. I’m really excited to read this one; these are two of the most thoughtful, pragmatic people in the opinion/analysis world, and I’m sure that whatever they come up with together will be well worth reading.

Over at the Chamber of Progress, Gary Winslett has released a roadmap for policymakers to make housing, energy, health care, and child care less expensive for regular Americans. It’s targeted at Democrats, but much of it could theoretically be embraced by anyone. Some of his proposals include:

Zoning reform, eliminating parking mandates, etc.

Encouraging cheaper housing construction techniques and denser forms of housing (mass timber, prefab, single-stair construction, etc.)

Permitting reform

Bring in more foreign doctors, lift the cap on medical residencies, and allow nurse practitioners and physicians’ assistants to do more kinds of care

Accelerated FDA approval processes

Repealing certificate-of-need laws

Various child care subsidies, child tax credits, free school lunches, etc.

Deregulate telemedicine

This all sounds like good stuff to me.

Meanwhile, the Institute For Progress has a list of ideas on how to reform NEPA, America’s main environmental review law. There are a lot of details in there, but the basic ideas are to A) reduce the number of development projects that are subject to NEPA in the first place, B) reduce the use of the most onerous kinds of environmental reviews, and C) make it a lot easier to exempt projects from NEPA.

I support that, of course. But Eli Dourado makes a powerful case that NEPA simply needs to be repealed instead of incrementally reformed. Doing that would require bureaucrats themselves to check whether development projects satisfy environmental laws (which would require hiring a lot more civil servants). The public could be allowed to comment and complain about projects, as in Japan, but wouldn’t be able to sue to force developers to do years of paperwork.

Anyway, all these are ideas worthy of consideration, and I’m glad to see that people from various political backgrounds are thinking along these lines. The more we can refocus America on abundance and away from bruising zero-sum culture-war battles, the better-off the nation will be.

5. Lina Khan misunderstands competition in the tech industry

I supported the new antitrust movement, but it always had some major problems. Chief among these was the idea that the threat of powerful companies doesn’t come from economic power — lower wages, higher prices, reduced innovation, and so on — but from political power. The “neo-Brandeis” movement, headed by Lina Khan, argued that the real threat was that companies like Facebook and Google would usurp democracy itself.

This idea was pernicious because it necessarily turned antitrust authority itself into a tool of political power — basically, the government using a lever of economic policy to go after companies it saw as rivals for power. It also helped alienate the tech industry, which is a major reason DOGE is tearing up the civil service as we speak.

Constantly thinking about antitrust through the lens of political power also tends to cloud antitrust authorities’ judgement — if they’ve decided Facebook and Google are their political enemies, they’ll tend to interpret innocuous events as evidence of those companies’ power. I think something like that is going on in Lina Khan’s recent New York Times op-ed, in which she argues that China’s new AI DeepSeek proves that the U.S. tech industry is uncompetitive. Khan writes:

[DeepSeek’s] innovations are real and undermine a core argument that America’s dominant technology firms have been pushing — namely, that they are developing the best artificial intelligence technology the world has to offer…For years now, these companies have been arguing that the government must protect them from competition to ensure that America stays ahead…

It should be no surprise that our big tech firms are at risk of being surpassed in A.I. innovation by foreign competitors. After companies like Google, Apple and Amazon helped transform the American economy in the 2000s, they maintained their dominance primarily through buying out rivals and building anticompetitive moats around their businesses…While monopolies may offer periodic advances, breakthrough innovations have historically come from disruptive outsiders…

In the coming weeks and months, U.S. tech giants may renew their calls for the government to grant them special protections that close off markets and lock in their dominance…Enforcers and policymakers should be wary…The best way for the United States to stay ahead globally is by promoting competition at home.

Khan’s arguments simply make no sense. First of all, the leading U.S. AI companies are not the Big Tech companies that Khan has spent her career going after. They’re OpenAI and Anthropic, which are both fairly recent startups. Yes, Google and Meta have some good LLMs, but they’re not ahead. The triumph of startups over Big Tech (so far) in the AI field is exactly how competition is supposed to work. Little upstarts successfully disrupted and upstaged the big incumbents.

Second of all, no U.S. AI company that I know of is calling for the government to protect it from domestic competitors. You just don’t see Google or Facebook calling for protection from American AI startups — or Canadian or French or Japanese AI startups. You do see a few U.S. AI companies calling for enhanced export controls on China. But this is because they worry that China’s government will put its own thumb on the scale for its national champions, thus killing competition in the industry.

Khan’s argument, in a nutshell, is that the U.S. should avoid doing anything to inconvenience China’s AI industry, as this would make U.S. AI giants more complacent, ultimately resulting in a Chinese competitive victory. That argument doesn’t make a lot of sense. The U.S. AI industry is already incredibly competitive, and the claim that export controls will ultimately strengthen China’s competitiveness by degrading its ability to present a competitive threat to American companies seems clearly self-contradictory.

What I think is happening here is that Lina Khan and many other progressives decided in the late 2010s that big U.S. tech companies have gotten too big for their britches, and need to be taken down a peg. This fixed belief has come to dominate their thinking about any issue involving technology. All they have is a hammer, so everything looks like a nail.

6. How AI will change the science field, according to AI

OpenAI has a new model out called Deep Research that will write an essay for you that looks like a research paper. It uses OpenAI’s most advanced “reasoning” models, as well as tools for searching the internet in real time. It’s pretty cool, though you have to have the $200-a-month “pro” subscription in order to use it.

Anyway, Kevin Bryan tried it out, asking it to write a paper about — appropriately enough — the future uses of AI in quantitative social science research, and how those fields will have to change to accommodate AI. And in both Bryan’s opinion and my own, the AI spat out a bunch of reasonable stuff! Here’s what it had to say about AI’s potential use cases:

AI’s role in academic writing has expanded rapidly in recent years. Modern language models can now assist in nearly every stage of the writing process, from initial idea generation to polishing a final draft…In one study, 50 journal article titles were given to ChatGPT to generate corresponding abstracts; the resulting AI-generated abstracts were often hard to distinguish from genuine ones by experts…AI models can condense lengthy papers or datasets of literature into concise summaries. This is particularly useful for literature reviews…Some experimental systems allow a user to query an AI for relevant literature on a topic, and the AI can return not just summaries but also citations to pertinent papers…

Beyond writing existing knowledge, AI tools are increasingly being used for ideation in research. Large language models can act as brainstorming partners, generating hypotheses or suggesting new research questions…Van Dis et al. (2023) reported that ChatGPT could outline components of a scientific study when prompted appropriately, although with errors and gaps that require human correction. These experiments illustrate an emerging trend: AI as a collaborator in the conceptual phase of research.

And here are some of its thoughts (or “thoughts”) about the dangers of using AI in science:

Despite their impressive capabilities, current AI writing models have notable limitations. A primary issue is factual accuracy. LLMs often “hallucinate” – they can produce plausible sounding statements that are incorrect or even fabricate references that look real but are non-existent (Thorp, 2023)…As Thorp (2023) noted, ChatGPT and similar models sometimes output references to studies that simply do not exist, a profoundly concerning behavior in a scholarly context…

To mitigate this, the incorporation of retrieval (searching for information) during generation is a promising trend…By grounding answers in actual source material, models are less likely to hallucinate. Another improvement is fine-tuning models on domain-specific academic text, which can make their output more knowledgeable and in line with the conventions of academic writing in a field…

The use of AI blurs the lines of authorship and originality. If a large portion of a manuscript is written by an AI, to what extent can the listed human authors claim original writing?…[R]esearchers might unwittingly commit ethical breaches by over-relying on AI and failing to properly disclose its role…Even if done with good intentions, lack of transparency about AI use can be seen as deception in the academic community…

Relatedly, AI could enable new forms of academic misconduct. For instance, a person could ask an AI to write a paper about results that do not actually exist (fabricating data and analysis)…

Even if one uses AI with honest intentions, there is the risk of overreliance. Researchers might become dependent on AI for tasks that they themselves should know how to do, such as critically reviewing literature or performing statistical analysis. If AI becomes a crutch, the depth of researchers’ own understanding could suffer.

And here are its predictions for the near future:

It is likely that AI writing assistants will become as common as spelling or grammar checkers are today. By 2035, most quantitative social scientists (and academics in general) will routinely use AI tools in drafting manuscripts and reports. This does not mean AI will replace researchers as writers, but it will be a standard part of the workflow. Just as researchers now might run a grammar-check or use reference management software, in the future they might use an AI to generate a first draft of an abstract or to suggest alternate phrasings for clarity…

We will likely see AI models specialized by discipline or even sub-discipline…By 2035, AI systems might not only write text but also handle data analysis as part of the writing process. We predict that a researcher could feed raw data to an AI, ask it to perform a regression or create a plot, and the AI would output the results along with a written description of the findings, including the figure or table in LaTeX format…

[W]ithin 10 years, many journals will employ AI to screen submissions. This could involve AI checking for sections that appear AI-written or checking for common errors and inconsistencies. More ambitiously, AI might provide first draft peer review reports, identifying potential methodological flaws or missing citations, which human reviewers can then verify and build upon[.]

All of this sounds extremely reasonable to me. I can’t find much to disagree with here. It’s pretty amazing that all of this (and more) was generated in just 15 minutes by a large statistical algorithm with a search engine. Most importantly, the two sources it cites in the text I excerpted — Van Dis et al. (2023) and Thorp (2023) — are real. The “reasoning” models seem to be more accurate than traditional LLMs, but also a little more plodding and less creative — probably an inevitable tradeoff. They also still “hallucinate” sometimes, meaning they have a long way to go before people trust them the way they trust human authors (deservedly or no).

But anyway, the technology appears to still be advancing rapidly. Soon I’ll see if I can use the new reasoning models to write a blog post! This has always failed when I’ve tried it in the past, but this Deep Research essay is so good that I’m going to try again.

The comptroller of the currency is actually a bank regulator.

The upstream industries are things like batteries, chips, and robots, while the downstream industries are things like EVs, phones, and drones.

In #1, you have a literal graph of an overwhelming majority of US adults believing that Elon Musk, a Big Tech billionaire, has too much influence over the US government.

Then in #5, you write "the real threat was that companies like Facebook and Google would usurp democracy itself" as if this is somehow crying wolf...

We literally have a tech billionaire getting access and control (according to his own tweets) of vast swathes of the US government.

How do you reconcile the "these silly antitrust people were wrong to worry about the political power of big tech" in point #5, with the the "the US government is going through a massive chaos blitz, much of it based on the design and guidance of a big tech billionaire based on the practices of his big tech company"?

The specific point about AI regulation vis a vis China is fine and it is convincing, but Lina Khan being wrong about the competitive advantages or disadvantages in one piece of the tech ecosystem, doesn't make the larger worry about the political power of big tech wrong.

Not seeing Big Techs as problem, while Elon is in the White House and Twitter/Meta have a lot of racist things in their feeds, is ridiculous. It’s kind of a confession of the error your argument that they take government because they were “alienated” and, therefore, they are not a problem. Given that you once encouraged Elon to buy Twitter, and that we now see that such transaction turned out horribly, I think you need some reflection about the subject.