At least five interesting things: Smart Ideas edition (#71)

Antitrust; Passive investing; Export controls; Overtourism; Selective immigration

Hi, everyone! I’m overdue for a roundup post.

First, I have a lot of podcasts for you! Here’s me arguing with the noted right-wing Frenchman Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry about high-skilled immigration:

And here’s Razib Khan interviewing me about Japanese politics:

Here’s an interview I did with the Media Summit podcast, about various media-related topics:

And here is an episode of Econ 102, discussing the future of American manufacturing.

OK, I know that was a lot. So without further ado, let’s move on to this week’s list of interesting things!

1. Are we wrong on antitrust?

In the 2000s and 2010s, America generally saw slow growth, low levels of business investment, and low business dynamism. We also saw increasing levels of corporate concentration, at least at the national level. A bunch of economists put two and two together, and hypothesized that growing monopoly power was choking off the economy. This wasn’t actually the impetus behind Lina Khan and the “neo-Brandeisian” antitrust movement, but it was probably the reason why very few economists stood up and criticized Khan’s policies.

In the last few years, however, a new wave of research has been coming out, suggesting that the market power picture is a lot more complicated than it once seemed. For example, Albrecht and Decker (2025) found that at the industry level, there was no correlation at all between price markups (an indicator of monopoly power) and business dynamism. In fact, industries where companies mark up their prices more tended to have slightly more new businesses enter the industry. This suggests that the story a lot of people were telling in the 2010s — that big powerful companies were blocking startups from taking off — wasn’t true.

Another interesting paper is Creanza (2025), which studies what happened when a whole bunch of American companies merged around the turn of the 20th century. This wave of mergers helped spur popular concerns about monopoly power. But Creanza finds that it also led to greater innovation at the corporate level. Basically, big industrial companies tended to have big industrial research labs that made a lot of discoveries:

This paper studies the Great Merger Wave (GMW) of 1895–1904—the largest consolidation event in U.S. history—to identify how Big Business affected American innovation. Between 1880 and 1940, the U.S. experienced a golden age of breakthrough discoveries in chemistry, electronics, and telecommunications that established its technological leadership….I show that consolidation substantially increased innovation…The establishment of corporate R&D laboratories served as a key mechanism driving these gains…[L]ab-owning firms enjoyed a productivity premium…Overall, the GMW increased breakthroughs by 13% between 1905 and 1940, with the largest gains in science-based fields (30% increase).

This is not a new idea. A lot of economists, including John Kenneth Galbraith, Joseph Schumpeter, and William Baumol have theorized that an upside of market power is that big profitable companies are able to afford big expensive labs, and that as long as there’s some competition, the whole economy can benefit from the resulting innovation. Bell Labs (pictured at the top of this post) is certainly the most famous example of a big, powerful company that plowed money back into useful research. In fact, two of this year’s Econ Nobel winners, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, won the prize for a theory saying that oligopoly enhances innovation. So it’s interesting to see Creanza find some historical data in support of this classic theory.

In fact, we can see this effect happening in AI today. Three big companies with a lot of market power — Google, Meta, and Microsoft — have been instrumental in driving the AI boom. In fact, many of the fundamental advances that power modern AI were made in Google’s labs. But those three companies have also benefitted from strong network effects that give them extraordinary market power and high profits — Google in search ads, Meta in social networks, and Microsoft in PC operating systems. All three companies have been targeted and even villainized by Lina Khan’s new antitrust movement. But perhaps without their market power, we wouldn’t have the AI boom that’s now the main thing sustaining our economy.

The antitrust push of the last decade may have missed some very big and important parts of the story.

2. An interesting idea about passive investing

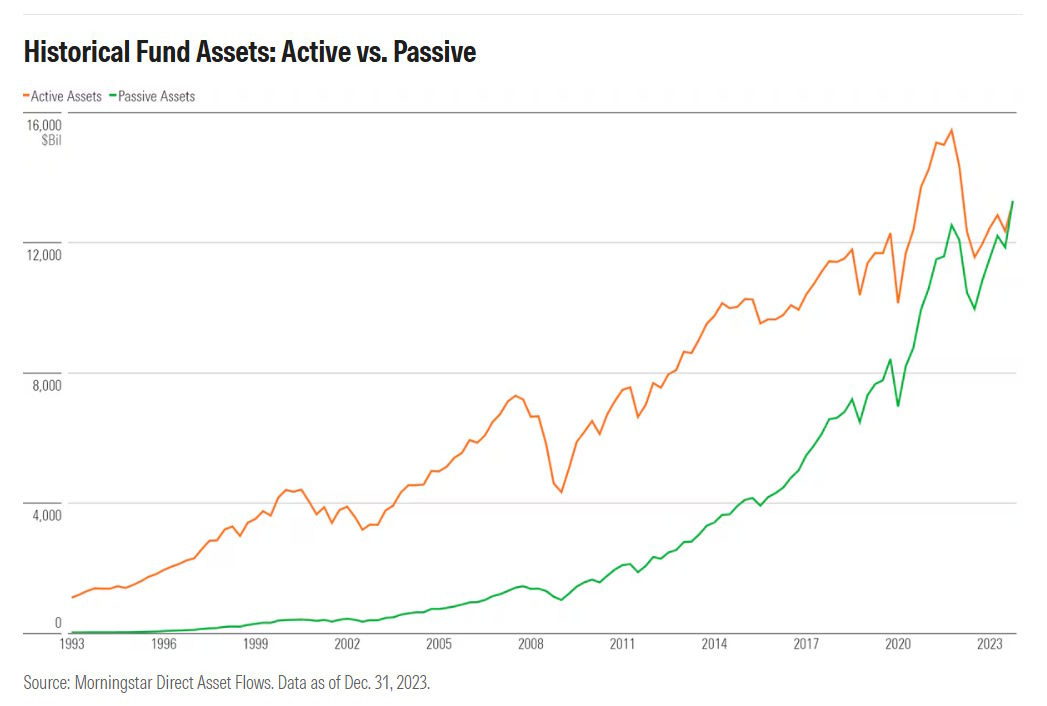

In recent decades, there has been a big shift from active to passive investing. Why spend all that time and effort picking stocks, when you can just buy an index fund or an ETF and automatically do as well as the market average — without spending any effort or paying any fees?

This logic is incredibly powerful, and it’s why passive investing has inexorably taken over from active investing:

But what if everyone in the market starts doing this? If there are no stock-pickers — only people who click a button that says “buy ETF” — who will do the research required to figure out if each stock is actually worth buying? And if everyone is buying or selling the same stocks at the same time, isn’t that somehow dangerous? What about corporate governance? If a few asset managers like Vanguard and Blackrock own all the companies, doesn’t that reduce competition? Etc. etc.

Those are long-standing concerns about passive management, and they get debated back and forth. But now we have a new potential drawback to worry about: underinvestment. Kontz and Hanson (2025) reason that when stocks become more correlated, they become riskier — the classic concept of “beta”. Riskier stocks are cheaper, because risk is bad. When stocks are cheaper, it’s harder for companies to sell their stock to finance business expansion. So Kontz and Hanson argue that because passive investing increases correlations, it suppresses real investment, because it makes it harder for companies to sell their stock.

That’s a plausible story, but I think it’s questionable how important it is for the overall economy. Passive investing really took off around 1995. But corporations’ cost of borrowing actually fell from 1995 through 2021:

That’s probably mostly due to things like interest rate cuts and new institutional money entering the market. But it suggests that even if passive investing is making it harder for companies to sell their stock, it’s not the big driving factor in America’s real investment drought.

Still, something to keep in mind.

3. Export controls on China are working

A lot of people expected Donald Trump to offer to sell Nvidia’s Blackwell chips to China as a concession in the recent China-U.S. trade talks. Nvidia’s CEO, Jensen Huang, had certainly been pressing hard for such a move, which would make his company a lot of money. But in the end, Trump held firm and refused to sell China the chips:

Greenlighting the export of Nvidia’s Blackwell chips would be a seismic policy shift potentially giving China, the U.S.’s biggest geopolitical competitor, a technological accelerant. Huang—who speaks to Trump often—has lobbied relentlessly to maintain access to the Chinese market.

As they prepared to meet Xi, top officials including Secretary of State Marco Rubio told Trump the sales would threaten national security, saying they would boost China’s AI data-center capabilities and backfire on the U.S., the officials said…

Faced with nearly unified opposition from his top advisers, Trump decided not to discuss the advanced Nvidia chips during his Oct. 30 meeting with Xi…Trump’s ultimate decision marked a victory for Rubio and other Trump advisers over Huang, leader of the world’s most valuable public company.

Was this a good outcome? The typical argument against export controls is that they spur China to create its own domestic chip supply chain, and reduce their reliance on America. Basically, the idea is that if we don’t do export controls, our companies can make money selling chips and chipmaking equipment to the Chinese, while at the same time keeping China dependent on our products. But if we stop selling chips and equipment to China, the argument goes, they’ll unleash their mighty innovation machine and learn how to make everything themselves, thus removing any leverage we might have had over them.

This was never a very compelling argument. If you want to keep China hooked on American products for strategic reasons, it’s probably a bad idea to scream “HEY CHINA, WE’RE SELLING YOU CHIPS AND EQUIPMENT SO YOU’LL STAY HOOKED ON OUR PRODUCTS, FOR STRATEGIC REASONS!!”. China’s leaders, being smarter than, say, a gerbil, will refuse to take this bait, and will work hard on developing their own indigenous chip supply chain anyway. Which is exactly what they’ve been doing for over a decade now.

It therefore seems fairly obvious that selling China chips and equipment will simply speed them along in their quest not only to become independent in semiconductors, but to dominate the global market for semiconductors. They will simply reverse-engineer both chips and equipment, while also using the equipment we sell them to make a bunch of chips.

This fairly obvious realization was exactly why we implemented export controls in the first place. And there continues to be evidence that those export controls are working as designed — not destroying China’s chip industry, but slowing it down substantially. For example, China is having trouble replicating ASML’s chipmaking equipment, as Brandon Weichert reports:

Apparently ASML DUV machines that China has to make their chips recently broke down. They called the Dutch company for help repairing it. ASML sent some techs. They discovered that the Chinese broke the machine when they disassembled it and tried to put it back together…The reason Chinese techs disassembled their older ASML DUV machine is because they are desperately trying to evade the US sanctions imposed upon them for the newest ASML-type machines. By disassembling their older one & trying to reassemble it, Chinese techs learn…They are trying to reverse-engineer what they have as a means of figuring out how to indigenously build their own, more advanced versions, to end-run the US sanctioned machines. But they can’t figure it out, apparently.

Meanwhile, China’s Huawei, which has reportedly suffered from low yields on its 7nm chips due to U.S. export controls, is now downplaying the importance of making 7nm chips at all. Everyone made a big deal about it back when Huawei’s supplier SMIC managed to make a 7nm chip at all, and the pro-China crowd boasted that export controls were ineffectual, but SMIC’s progress appears to have stalled:

Despite concerted efforts by China to bolster domestic semiconductor production in defiance of US trade policy, new evidence uncovered by Canadian research outlet TechInsights suggests SMIC, the Middle Kingdom’s top chip manufacturer, remains generations behind the rest of the world…TechInsights confirmed that the Kirin X90…in Huawei’s Matebook Fold was fabbed on SMIC’s now two-year-old 7nm N+2 process. The findings debunk rumors the SoC would be fabbed on a homegrown 5nm process node…SMIC has been rumored to have developed an even more sophisticated 5nm process node also using DUV technology. However, as TechInsights points out, chips based on the tech remain elusive.

Meanwhile, China’s technologists themselves seem pretty upset about the export controls, and admit that they’re holding back the country’s AI industry. Here are a couple of quotes:

Here’s a more detailed story about Tencent’s struggle to make cutting-edge AI models under export controls.

So anyway, export controls are definitely holding back not just China’s chipmaking industry, but its AI industry as well. Those industries won’t be destroyed, but they’ll probably keep lagging behind the U.S., especially if the chip controls are tightened. And as long as those industries lag, China may be a little bit more reluctant to start a major war.

If I were in charge, I would keep the export controls in place, and tighten them up as much as possible.

4. The obvious solution for Japan’s overtourism problem

Tourists are becoming a problem for Japan. Tourism keeps rising and rising, pouring revenue into the country but also putting a huge strain on the urban infrastructure of Kyoto and Tokyo (the most popular destinations). The roads and trains simply can’t handle that many people. Meanwhile, many tourists from the U.S. and other Western countries are badly behaved, straining Japanese society. Overcrowding contributes to that problem, by making tourists too numerous to police.

And yet forcibly cutting down on tourism would deprive Japan’s long-stagnant economy of needed revenue (and foreign exchange earnings). Plenty of neglected cities, like Nagoya, actually want more tourists. The Japanese government has tried various measures to nudge foreign travelers away from Kyoto and Tokyo and toward those neglected areas. The effectiveness of those measures, however, has been very patchy.

But Kyoto recently enacted a policy that promises to counter overtourism in a particularly elegant and efficient way:

Desperate to thin out tourist crowds here, the city government will slap visitors with an accommodation tax of up to 10,000 yen ($68.3) per person per night, starting March 1…Officials explained that the 10,000-yen levy will apply to hotel stays costing 100,000 yen or more per night…After the revision, the city’s lodging tax revenue is projected to roughly double, from approximately 5.91 billion yen this fiscal year to 12.6 billion yen next fiscal year.

This is a Pigouvian tax! The city’s congestion problem is an externality. And when you have an externality, you want to tax it. Hotel fees can be set to balance the city’s desire for tax revenue with its desire to reduce overtourism.

Several modifications to this policy immediately suggest themselves. First, Japanese people travel from city to city for business, and the government probably doesn’t want to tax this. So the full hotel fee should apply only to reservations made from foreign bank accounts.

Second, it’s pretty easy to stay in Osaka and commute to Kyoto, so hotel fees should be coordinated regionally.

Region-specific hotel fees accomplish multiple objectives:

They reduce overtourism.

They raise tax revenue for city governments.

They redirect tourists toward cities without fees, which need the tourism revenue more.

It solves three problems at once, with very little downside.

5. Selective immigration is powerful

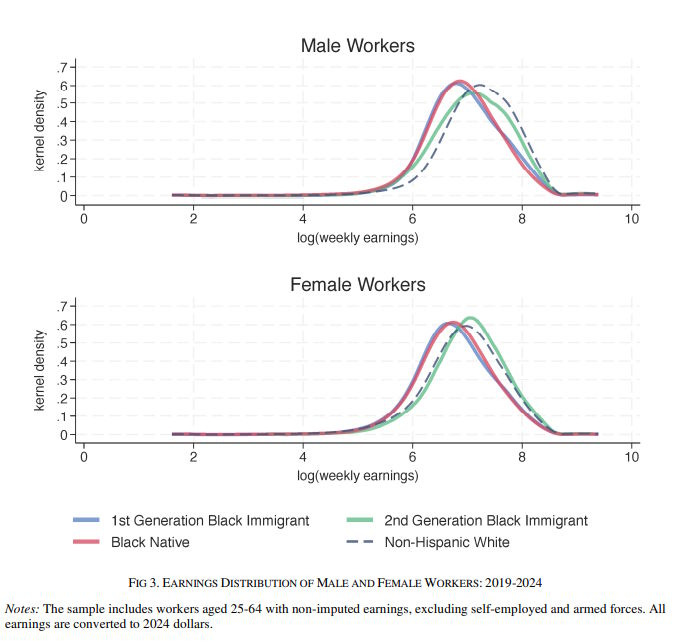

Earnings gaps between Black and White Americans have begun to narrow. But a new paper by Ru, Kaushal, and Muchomba claims that essentially all of this improvement has been due to highly selective immigration:

Our results show remarkable earnings parity between 2nd-generation Black immigrants and non-Hispanic Whites, with Black women leading the progress. The gap is falling for 1st-generation Blacks but remains stubbornly high for native Blacks. Underlying the extraordinary performance of 2nd-generation Blacks is their exceptionally high and escalating educational attainment.

Here’s a chart showing 1st-generation Black immigrants, 2nd-generation kids of Black immigrants, White Americans, and Black Americans with no recent immigrant ancestry:

As you can see from that chart, Black immigrants earn about as much as native-born Black Americans. But 2nd-generation Black Americans earn about as much as White Americans.

There are several important implications of this finding.

First, selective immigration is very important. The kids of Black immigrants to America move up in the world because they’re highly educated. Selecting for immigrants that value education is therefore a way of reducing racial gaps in America — in addition, of course, to the substantial contributions they make to America’s economy.

Second, fears of segmented assimilation — the idea that the kids and grandkids of Black immigrants will end up with economic trajectories similar to those of native-born Black Americans — seem overblown.

Third, America is a land of opportunity for Black immigrants, but not nearly as much so for Black people whose families have been here a long time. This means that the “ADOS” concept — meaning Black Americans whose ancestors were slaves — is probably a useful one. It defines the group of people who most need help from the government. For example, affirmative action programs targeted at Black people in general are likely to award college spots to the kids of elite African immigrants. Instead, in the interest of maximum efficiency and fairness, they should probably be targeted at ADOS specifically.

Minor pedantic point. The articles uses “Black immigrants” and “African immigrants” interchangeably.

The majority of Black immigrants don’t immigrate from Africa. The biggest source of Black immigrants is the Caribbean - Jamaica and Haiti, specifically.

I imagine as passive investment grows to become a larger and larger share of market activity, the opportunity for exploiting pricing inefficiencies also grows, increasing the potential reward for price discovery. I imagine there is an equilibrium somewhere that most markets will settle around.