At least five interesting things to start your week (#23)

SF's Market Street debacle, the debate over real wages, why U.S. growth has gotten smoother, TikTok as a propaganda engine, and California homelessness

I hope everyone had a very merry Christmas, and is prepared to have a happy New Year! I’m headed out of town for a few days, but don’t worry; I will continue working day and night to provide you with the Noahpinion content you crave.

Today I have LOTS of podcast material for you, so those of you who enjoy listening to my gravelly mellifluous voice are in luck!

First, I appeared on the #InnoMinds podcast with Taiwan’s Minister of Digital Affairs, Audrey Tang! It’s only on YouTube, but here are the two parts of the epic discussion:

On top of that, Erik Torenberg and I recorded not one, but TWO episodes of our podcast, Econ 102. The first is about immigration, the second is about inflation:

And here are Apple Podcasts and YouTube links for the immigration episode, and Apple Podcasts and YouTube links for the inflation episode!

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things.

1. San Francisco’s Market Street debacle helped destroy its downtown

Paris looks really nice these days. A sustained effort to kick cars out of the central city has resulted in many streets becoming pleasant pathways for bicycles and pedestrians. Some urbanists in the United States hope to copy this model. But unfortunately, the place they chose to start copying it was downtown San Francisco.

This turned out to be a huge mistake. Cars have indeed been banned from SF’s central downtown thoroughfare, the famous Market Street. But they have not been replaced by bikes and pedestrians. There are a scattered few cyclists, but not many; SF is a very hilly city, so many people don’t use bikes. And pedestrians aren’t even allowed in the middle of Market Street, lest they be hit by the occasional bus or streetcar that actually does use the road — Market Street is not a promenade.

Thus, instead of the Champs Elysees, Market Street now resembles a giant empty parking lot running right through the middle of downtown — a barren asphalt scar on a half-deserted urban landscape. Between the Market Street closure and the emptying out of downtown offices due to remote work, downtown SF is dying; without foot traffic or car traffic, stores and malls have been closing left and right. The whole area feels as if it’s stuck forever in the pandemic.

But in fact, the Market Street closure is part of a larger debacle of urban politics and governance that has seen the city of San Francisco spend hundreds of millions of dollars to destroy its most important commercial area. This story in the San Francisco Standard tells the tale, and it’s absolutely worth your time if you want to understand why SF is so dysfunctional. Here are just a few short excerpts:

A $600 million capital project called Better Market Street promised to create a futuristic boulevard that would safely buffer bicycles and scooters on elevated sidewalk lanes…More than a decade of planning went into alterations of Market Street…

Today, the scene on the ground is almost unrecognizable compared to San Francisco’s grand promises. Yes, cars are gone from Market Street. But so are people…[F]unds for anything beyond modest improvements along a three-block stretch of Market Street between Fifth and Eighth streets—expected to be finished next summer—have evaporated. City departments are now passing the responsibility of explaining what went wrong with the project like a hot potato…

“Even if the transportation bonds had passed and we were not facing a fiscal cliff, I think there would still be a real question of whether we should move forward with Better Market Street as it’s been envisioned,” [Supervisor Rafael] Mandelman said. “We need to walk into these giant projects eyes wide open and really think through how long they’re going to take and how much they’re going to cost. I don’t think Better Market has yet met that test.”

Anyway, if you feel like being infuriated, read the whole thing.

2. The fight over real wages

One big point of contention in the whole “vibecession” debate has been whether real wages have gone up or down for American workers. If real wages go up, it means that even with rising prices, people’s purchasing power has increased; if they go down, it means lots of Americans are becoming impoverished. In general, both conservatives and leftists (who both dislike Biden) argue that wages have done poorly, while liberals argue wages have done well.

Matt Bruenig created a good graph making the argument that real wages have done poorly. It uses survey data to look at wage changes for specific individuals who had jobs from 2017 to 2023; this avoids composition effects from the hiring and firing during the pandemic The result is pretty much the conventional wisdom — median real wages fell in 2021 and 2022, before beginning to rise again in 2023:

This is exactly what you’d see from a regular old “real wages” graph. It supports the notion that the U.S. economy is doing well for the typical worker in 2023, but did poorly in 2021-22.

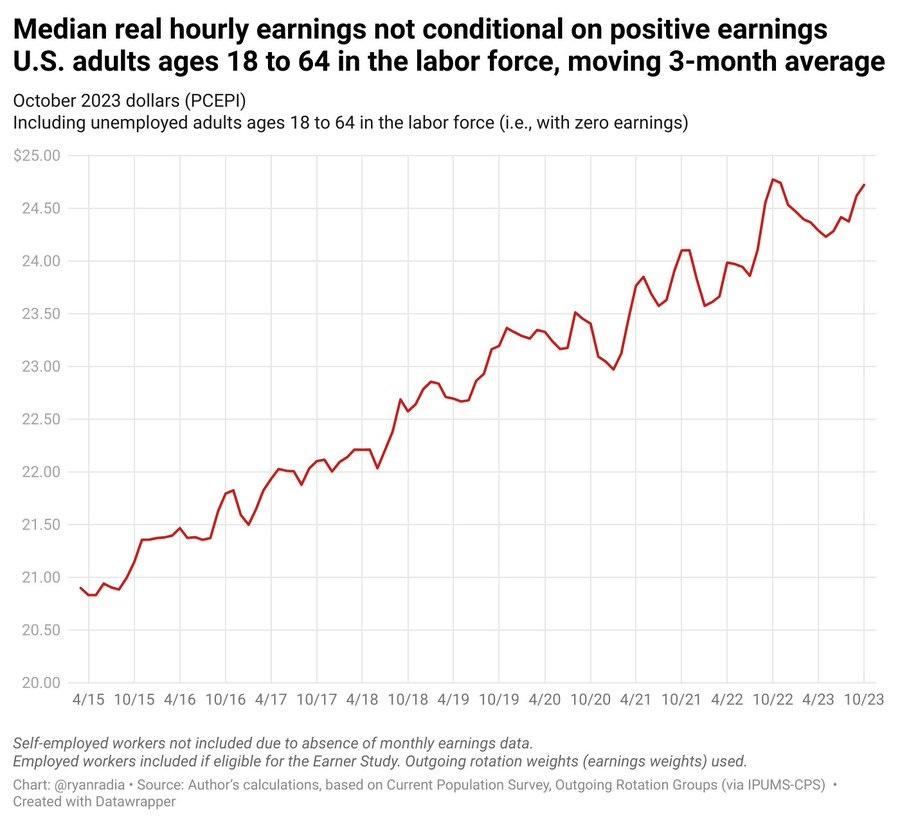

But using the same survey data, Ryan Radia created a very different graph, looking at the median of wages for all working-age adults in the labor force. And it shows a bumpy but definitely upward trend throughout 2021 and 2022:

How can we reconcile these two graphs? The answer is that employment rates went up. A lot of people who didn’t have jobs in 2020 were employed in 2021, and a lot of people who didn’t have jobs in 2021 were employed in 2022. Bruenig’s graph doesn’t include these people at all, since it measures wages only for people who were employed throughout. Radia’s graph includes people who weren’t earning a wage at all in 2020 or 2021, which makes median wage growth look a lot better.

So which graph is the “right” one? In fact, I think both tell interesting and important stories. Many American workers saw their wages fall in 2021 and 2022, and they are naturally angry about that, even if their wages started growing again in 2023. But at the same time, the rise in employment rates under Biden means that a whole lot of the worst-off workers are now earning more. And the overall real wage gains since 2019 — when employment rates were also pretty high — points to a steady underlying improvement in the American economy’s ability to deliver for workers.

As is so often the case in economics, the real story is a nuanced and complex one.

3. Why recessions aren’t common anymore

U.S. economic growth has been remarkably steady over the last two centuries. But in the past, it was a lot bumpier. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the U.S. economy spent a lot of its time in recession. But ever since the Great Depression, recessions have typically been rarer and shorter:

What changed? The clear break point was the Depression and the FDR administration. Roosevelt increased banking regulation — for example, creating the FDIC — which made the financial system more stable. And he took the U.S. off the gold standard, which enabled the Fed to conduct much more aggressive monetary easing to stave off recessions. (The gold standard was officially restored after the war under the Bretton Woods system, but in practice this system gave the Fed so much leeway that gold didn’t constrain U.S. monetary policy at all.)

So which of these mattered more? In an article in the Journal of Economic Perspectives in 1999, Christina Romer argued that monetary policy was the more important factor. She wrote:

The most likely source of both the continuity and the change in economic fluctuations is the rise of macroeconomic policy after World War II…[M]acroeconomic policy and related reforms have eliminated or dampened many of the shocks that caused recessions in the past, and thus brought about longer expansions and fewer severe recessions…[W]e have replaced uncontrolled random shocks from a wide variety of sources with controlled policy shocks.

Using a simple model of the effects of Fed interest rate changes on the real economy, Romer shows what the postwar period might have looked like without monetary stabilization. It would have featured four sharp recessions instead of two mild ones:

Romer’s analysis ends in 1999, but it’s possible we have monetary policy in part to thank for the fact that the Great Recession that began in 2008 was far less severe than the Great Depression.

This isn’t a slam-dunk case — banking regulation was clearly also important, and it’s possible that subtler changes in technology and globalization had some effect as well. But this is a strong argument that macroeconomic stabilization policy is effective and important. All things considered, we’d rather our growth be smooth instead of bumpy.

4. TikTok is a silent engine of Chinese government propaganda

The case for forcing TikTok to be sold to a non-Chinese company usually rests on privacy concerns — it’s clear that the app funnels U.S. user data to the Chinese Communist Party, who can then use it to spy or to target specific individuals. But perhaps an even bigger concern is propaganda — through subtle manipulation of the algorithm, TikTok can steer Americans away from topics of discussion that are sensitive to the CCP, and toward CCP-approved points of view.

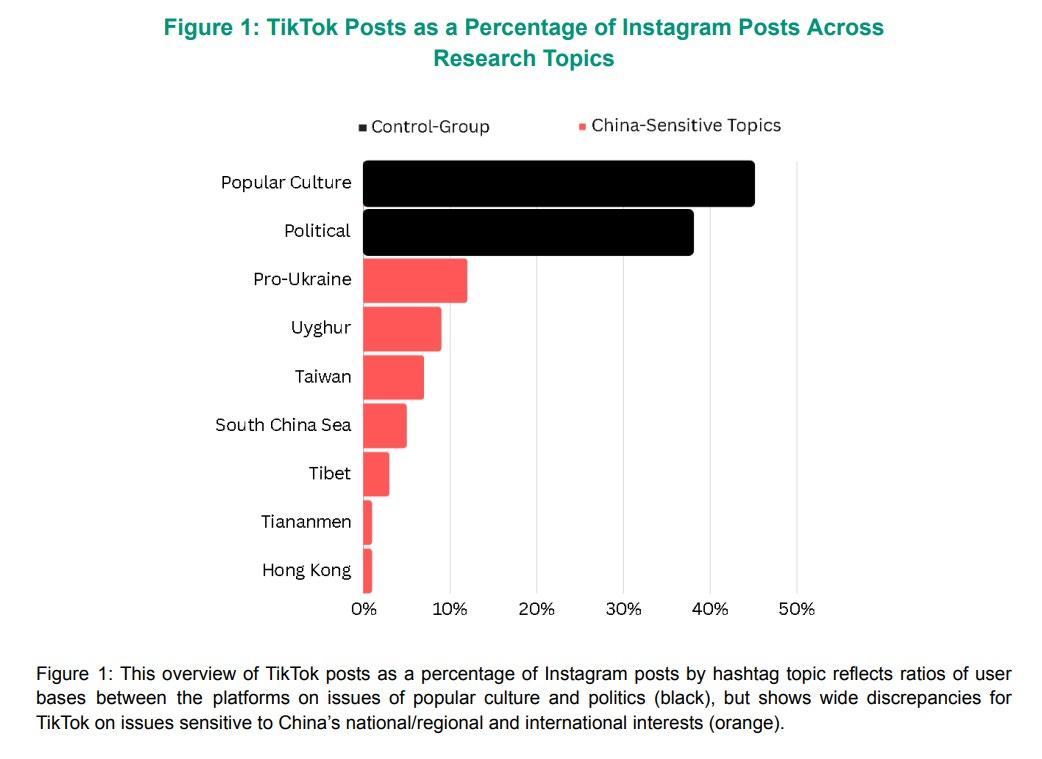

A new study by the Network Contagion Research Institute confirms that this is already happening, in a very substantial way. By comparing the hashtags of short videos on Instagram and TikTok, they can get an idea of which topics the TikTok algorithm is encouraging or suppressing.

The results are highly unsurprising for anyone who’s familiar with CCP information suppression. Hashtags dealing with general political topics (BLM, Trump, abortion, etc.) are about 38% as popular on TikTok as on Instagram. But hashtags on topics sensitive to the CCP — the Tiananmen Square massacre, the Hong Kong protests and crackdown, etc. — are only 1% as prevalent on Tiktok as on Instagram. The difference is absolutely staggering:

For some of these topics, differences in the user bases of the two apps might account for these differences — for example, TikTok is banned in India, meaning the topic of Kashmir is unlikely to be discussed on the app. But overall, the pattern is unmistakable — every single topic that the CCP doesn’t want people to talk about is getting suppressed on TikTok.

The question now is what should be done about this. Obviously, foreign media outlets are free to propagandize Americans, under the First Amendment. But when you read Russia Today or Xinhua, you know you’re getting propagandized. TikTok users may have no idea that the seemingly neutral platform app that they increasingly use to get their news is secretly inserting an editorial slant into that news. If Americans were sold toaster ovens that hacked into their phones and secretly blocked links to certain news stories, would that secret manipulation be protected speech under the First Amendment?

That’s obviously for the courts to decide. But I have the sinking feeling that if the U.S. can’t bring itself to force a sale of TikTok, we’ll have proven democracy incapable of defending itself against totalitarian states in the realm of information warfare.

5. American homelessness is a California problem

Homelessness in America increased over the last year, driven by the migrant crisis, the delayed effect of the end of pandemic eviction controls, and possibly by changes in measurement. The increase was most severe by far on the West Coast, which has emerged as the center of the homelessness problem in America.

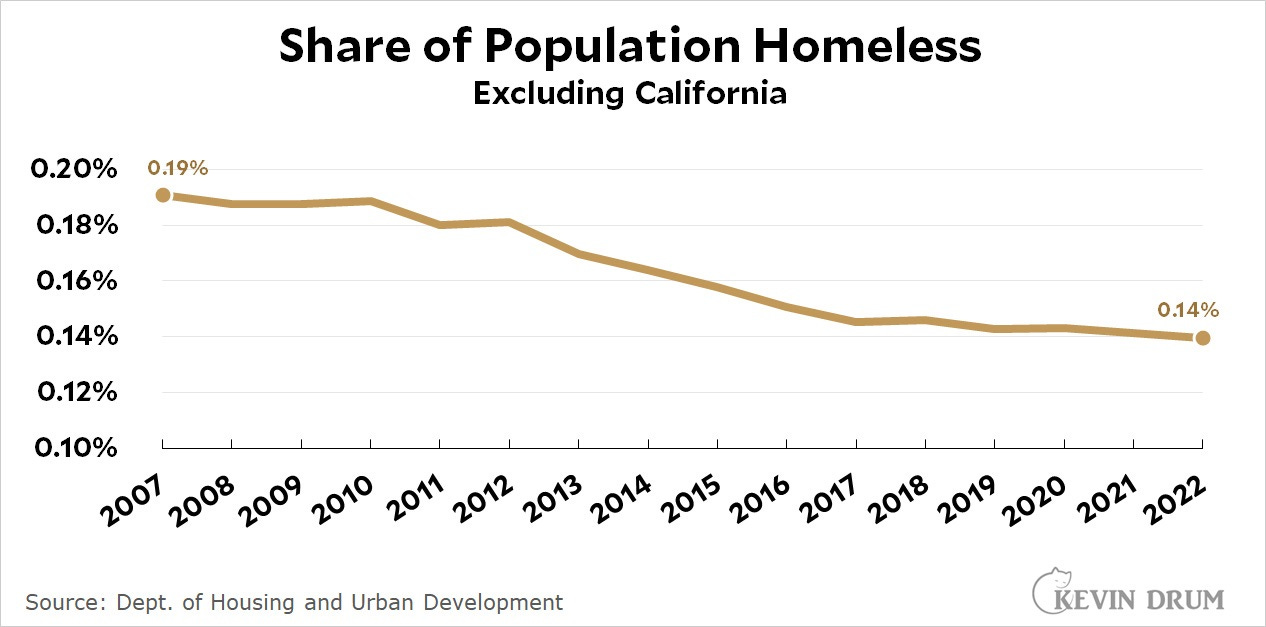

But Kevin Drum crunched the numbers and found a pretty startling fact: More than anything, American homelessness is specifically a California problem. If we exclude the Golden State, American homelessness is in long-term decline:

Darrell Owens has more data to back up the conclusion.

Until 2016 or so it might have been possible to claim that California simply wasn’t able to keep up with all the people moving to the state to take advantage of the sunny weather, the tech industry, Hollywood, and so on. But the state’s population has essentially been flat since then, as international inflows balance out domestic outmigration:

The real problem is simply that California makes it very very very difficult to build housing, with a dense thicket of zoning codes, cumbersome environmental review (CEQA), and other legal restrictions. Every day, a new story comes out about housing that takes decades to complete and ends up costing an astronomical amount.

As a direct result of these policy choices, California has gone from a haven for the middle class to a playground for the wealthy. The state’s leaders are finally beginning to understand the magnitude of the problem, and are taking steps to try to correct it. But they’re in a deep hole created by many decades of anti-development policy, and it will take a very sustained effort to turn things around.

“ . . . if the U.S. can’t bring itself to force a sale of TikTok, we’ll have proven democracy incapable of defending itself against totalitarian states in the realm of information warfare.”

It is simply stunning, given the U.S. has the CIA, NSA and a dozen more federal intelligence agencies, that the alarm bells haven’t been loudly ringing about the threat presented by a hostile foreign power shaping public opinion of young people. Imagine if the algorithm started targeting young men with anti-military propaganda, which may well be happening given the dismal recruiting efforts of the U.S. military.

TikTok is a grave threat.

The study on TikTok revealed that the Chinese are taking steps to suppress certain kinds of news. I wonder how we would figure out whether they are trying to insert certain kinds of news.