At least five interesting things: Nerdy economics edition (#54)

The DBCFT; Construction productivity and regulation; Rationality and complexity; U.S. productivity growth; Demand-side inflation; Health care monopsony and innovation

Ostensibly this is an economics blog. I know I’ve spent a lot of time recently ranting about land acknowledgements, or war, or the problems with the Democratic party, but really the point of all that is to get us back to a world that’s calm and rational enough where we can afford to spend our time thinking about wonky nerdy econ stuff. Right?

In the meantime, though, there’s always plenty of research to nerd out about. So that’s the focus of this week’s roundup.

But first, podcasts! Here’s a debate I did with Vitalik Buterin, creator of Ethereum, on the Bankless podcast a few months ago, which we just republished on Econ 102. We’re debating whether new technologies tilt the playing field toward authoritarian governments:

Vitalik never fails to have original and incisive thoughts on this and other topics.

Also, here’s this week’s Econ 102 episode, where Erik and I follow up on my post about land acknowledgements with a discussion about immigration and national identity:

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things!

1. The coolest tax idea you’ve never heard of (or maybe you have?)

When Trump did his tax reform in his first term, his team initially had a big idea that I really liked. It’s called the Destination-Based Cash Flow Tax, or DBCFT. It’s a way of reforming corporate taxation to promote investment and exports. Alan Auerbach had a good simple explainer of the DBCFT in 2017. Here’s his summary of what the tax entails:

[T]he DBCFT would replace the [corporate] income tax with a cash-flow tax, substituting depreciation allowances with immediate investment expensing and eliminating interest deduction for nonfinancial companies. On the international side, the DBCFT would replace the current “worldwide” tax system, under which US activities of US and foreign businesses and foreign activities of US businesses are subject to US taxation, with a territorial system that taxes only US activities plus border adjustment that effectively denies a tax deduction for imported inputs and relieves export receipts from tax.

Auerbach also explains that a DBCFT is mathematically equivalent to two other policies: a value-added tax (VAT) plus a wage subsidy.

I really liked the DBCFT, but sadly Trump chose to back off of most of its provisions. But in a recent post over at Cremieux’s blog, Jason Harrison argues that Trump should resurrect the idea:

Harrison explains several advantages of the DBCFT relative to our current method of corporate taxation:

It encourages companies to invest more, by allowing them to expense their investments immediately. (Note that immediate full expensing for R&D spending is especially important for growth.)

It stops encouraging companies to borrow too much money, as our current system does.

It makes it harder for companies to evade taxes by shifting profits overseas.

Harrison points out that the DBCFT is a form of consumption tax. Usually we think consumption taxes are more economically efficient than income taxes, because they don’t discourage savings and investment. The reason we often shy away from them is because consumption taxes are regressive — poor people consume most of their income, while rich people save most of theirs, so shifting from income to consumption taxes will hit the poor harder while exempting the rich.

But because DBCFT is equal to a consumption tax (i.e. a VAT) plus a wage subsidy, it doesn’t have this problem. It only taxes the part of consumption that comes from capital income, leaving consumption from labor income alone. Harrison explains:

[W]hile a VAT taxes all consumption, the DBCFT only taxes consumption financed from non-wage sources—mainly existing wealth (wealth accumulated before the reform that has already faced the income tax) and above-normal returns to investment.

One additional benefit of the DBCFT that Harrison doesn’t mention is that it promotes exports. If, like me, you’re a believer that export promotion is a key piece of industrial policy, then you should like the DBCFT.

So I strongly agree that Trump should bring back the DBCFT in his second term.

2. Construction productivity and regulation

Over the past few years, Americans have noticed that their country seems incapable of building much of anything. There are lots of facts that fit this general story. Two very important ones are:

Productivity in the construction sector has flatlined or even decreased since the mid-1960s.

Land-use restrictions are an important barrier to getting things built.

Here’s a picture of decreasing productivity in construction, via Goolsbee and Syverson (2023):

Intuition says that this is somehow connected to the land-use restrictions that we know are blocking development. Some authors, like Brooks and Liscow (2019), have pointed out that the timing for this explanation lines up very well. But there’s the question of how, exactly, land-use restrictions make the construction industry less productive. After all, once production gets greenlit, don’t the restrictions no longer matter? What’s making construction less productive even after it gets approved?

One possibility is that NIMBY legal challenges cause delays, which cause cost overruns. But in a new paper, D’Amico et al. (2024) argue that there’s a deeper force at work here. They hypothesize that land-use restrictions force construction companies to be too small and fragmented:

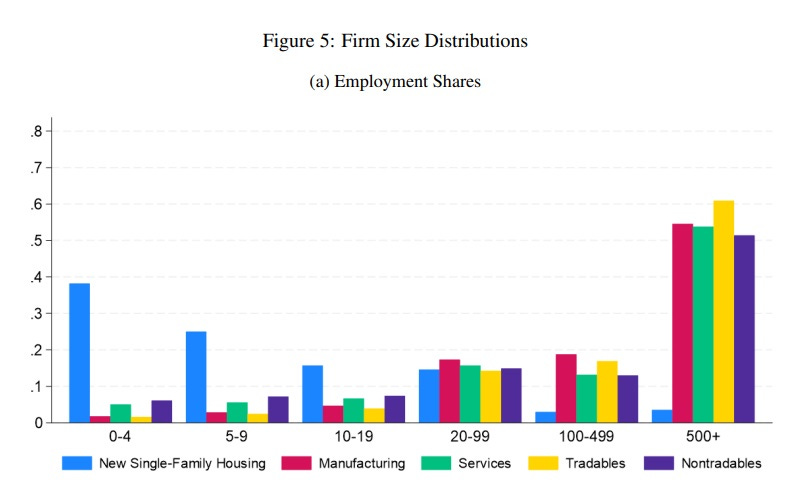

Homes built per construction worker remained stagnant between 1900 and 1940, boomed after World War II, and then plummeted after 1970. The productivity boom from 1940 to 1970 shows that nothing makes technological progress inherently impossible in construction. What stopped it? We present a model in which local land-use controls limit the size of building projects. This constraint reduces the equilibrium size of construction companies, reducing both scale economies and incentives to invest in innovation. Our model shows that, in a competitive industry, such inefficient reductions in firm size and technology investment are a distinctive consequence of restrictive project regulation, while classic regulatory barriers to entry increase firm size. The model is consistent with an extensive series of key facts about the nature of the construction sector. The post-1970 productivity decline coincides with increases in our best proxies for land-use regulation. The size of development projects is small today and has declined over time. The size of construction firms is also quite small, especially relative to other goods-producing firms, and smaller builders are less productive. Areas with stricter land use regulation have particularly small and unproductive construction establishments. Patenting activity in construction stagnated and diverged from other sectors. A back-of-the-envelope calculation indicates that, if half of the observed link between establishment size and productivity is causal, America’s residential construction firms would be approximately 60 percent more productive if their size distribution matched that of manufacturing.

This theory is cool because it connects both low construction productivity and land-use restriction with another important and well-known fact — the fragmentation of the construction industry. Construction companies are tiny compared to companies in other industries:

I love this model, and I think that the basic story is probably true. But I think there’s at one element that might be unrealistic. D’Amico et al. model land-use regulations as being fundamentally about construction project size — it’s harder to get larger projects approved, so construction companies have to focus on smaller ones. While that’s certainly true, I strongly suspect that there’s a much more important mechanism by which land-use restrictions limit economies of scale: regulatory heterogeneity.

Land-use restrictions are very different in different cities, and navigating the approval process in Baltimore doesn’t really make you better at navigating the approval process in San Diego. This means that it’s very hard to have a few giant Wal-Mart style construction companies that handle projects all over the country. I think if we’re looking for ways to increase construction productivity, harmonizing regulations across regions is probably more promising than simply approving more megaprojects.

Also, D’Amico et al. limit their empirical analysis to America. Why has construction productivity stagnated in other countries around the world, including countries like Japan that have very permissive land-use regulations? In general, I’m suspicious of single-country explanations for global phenomena. I think D’Amico et al. have identified an important factor, but I have a feeling there’s a lot more to this puzzle.

3. Are humans irrational or just confused?

When economists started making theories of human behavior, they generally assumed that everyone was “rational” — that they made decisions based on assessing all the available information in an optimal way, and maximizing their utility accordingly. Then in the 70s and 80s, some psychologists and behavioral economists did a bunch of experiments that showed people behaving in seemingly irrational ways. Often these experiments involved having people choose between “lotteries” — i.e., presenting them with two possible gambles, and letting them choose which one they’d rather take.

Behavioral economists found that people systematically made certain kinds of choices among these “lotteries” that didn’t seem to fit the textbook definition of rationality. One of the most popular explanations for these “anomalies” was something called Prospect Theory, created by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. It’s basically two theories in one. Part of Prospect Theory says that people exaggerate small probabilities in their decision-making. The other part says that people are loss-averse — their utility depends on a seemingly arbitrary reference point.

But a new paper by Ryan Oprea challenges the idea that we even need something like Prospect Theory at all. Oprea hypothesizes that a lot of the seemingly “irrational” experimental behaviors are really just due to the excessive complexity of the task they’re being asked to do. He does an experiment where he takes away all the risk in the decision — there are no probabilities and no losses involved. One option just gives you more money than the other. And yet experimental subjects still make mistakes that look a lot like the “irrational” choices they make in Kahneman-type experiments. Eric Crampton has a good blog post summarizing the details of Oprea’s experiment.

So it’s possible that a lot of what looks like “irrationality” is just human beings being unable to deal with complex calculations. That doesn’t kill the idea of behavioral economics — it just means we need different theories about why people don’t act like homo economicus.

As an example, Ben Moll has a new paper in which he challenges the use of rational-expectations heterogeneous-agent models in macroeconomics. He argues that these theories would require consumers to take way too much information into account in their calculations. Instead, he suggests that we need theories in which agents solve simpler problems, even if this results in a little bit of what seems like irrationality:

The thesis of this essay is that, in heterogeneous agent macroeconomics, the assumption of rational expectations about equilibrium prices is unrealistic, unnecessarily complicates computations, and should be replaced. This is because rational expectations imply that decision makers (unrealistically) forecast equilibrium prices like interest rates by forecasting cross-sectional distributions. The result is an extreme version of the curse of dimensionality: dynamic programming problems in which the entire cross-sectional distribution is a state variable (“Master equation” a.k.a. “Monster equation”). This problem severely limits the applicability of the heterogeneous-agent approach to some of the biggest questions in macroeconomics, namely those in which aggregate risk and non-linearities are key, like financial crises…I then discuss some potentially promising directions, including temporary equilibrium approaches, incorporating survey expectations, least-squares learning, and reinforcement learning.

That sounds right to me. I never understood why macroeconomics should assume that human agents are infinitely powerful calculating machines. It’s good to see people reexamining that approach.

4. America’s economic fundamentals are strong

The U.S. economy has been growing strongly in recent years. Part of that was just a function of putting people back to work after the shock of the pandemic. But a lot of it was due to productivity growth. American workers are producing a lot more in terms of output per hour than they did in 2016 or 2022. Joey Politano has the story:

In fact, the U.S. is almost unique among rich countries in terms of seeing its productivity grow since the pandemic! Everyone else is stagnating:

Productivity has grown in service industries while stagnating or shrinking in manufacturing — a change from the traditional pattern, and a big challenge to the conservative idea that government red tape is holding service industries back.

Politano attributes America’s productivity boom to three factors:

Increased capital intensity (companies investing more)

Increased reallocation of workers to new and better jobs

Increased creation of new companies since the pandemic

Note that the first of these challenges the progressive notion that companies have just been buying back their stock instead of investing.

In any case, this is great news. Productivity is the bedrock of economic performance — it drives long-term increases in wages and living standards, and it allows the Fed to keep interest rates lower without risking inflation. Something is going very right in the American economy that isn’t going right in other rich countries (or, at least since 2022, in China either).

5. Yes, some of the post-pandemic inflation was probably demand-driven

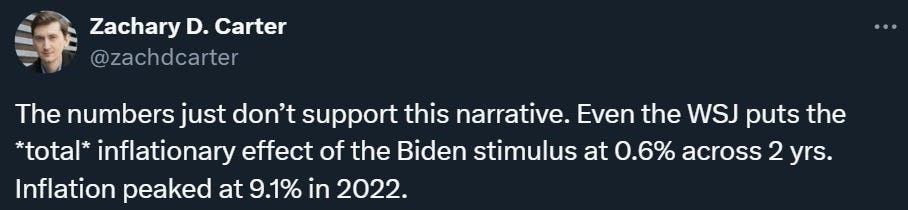

Everyone pretty much agrees that anger over inflation was one of the reasons Trump won the election this year. But some of the folks I call “macroprogressives” — people who tend to favor more fiscal stimulus in nearly any situation — continue to insist that inflation was mostly just a function of supply disruptions rather than an effect of Biden’s American Rescue Plan or Trump’s CARES Act. For example, here are Zachary D. Carter, Joe Weisenthal, and Kasey Klimes, citing analyses from the Wall Street Journal, Jan Hatzius, and Peter Orszag:

But with all due respect to Orszag, Hatzius, and the rest, I don’t think this case holds up.

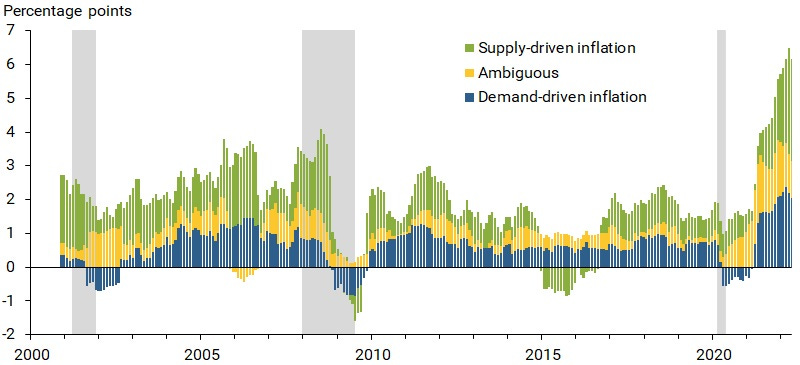

First of all, I’ve looked at a number of analyses of the post-pandemic inflation, and most of them ascribe a significant fraction — usually around half — to demand-side factors, especially in 2021. For example, this is from Adam Shapiro at the San Francisco Fed:

And this is from Òscar Jordà, Celeste Liu, Fernanda Nechio, and Fabián Rivera-Reyes, also at the San Francisco Fed:

And this is from Matthew Gordon and Todd Clark of the Cleveland Fed:

And here’s Giovanni et al. (2024), using a pretty standard model and cross-country evidence, and concluding that both demand and supply shocks contributed:

We employ a multi-country multi-sector New Keynesian model to analyze the factors driving pandemic-era inflation. The model incorporates both sector-specific and aggregate shocks, which propagate through the global trade and production network and generate demand and supply imbalances, leading to inflation and spillovers. The baseline quantitative exercise matches changes in aggregate and sectoral prices and wages for a sample of countries including the United States, Euro Area, China, and Russia. Our findings indicate that supply-chain bottlenecks ignited inflation in 2020, followed by a surge in prices driven by aggregate demand shocks from 2021 through 2022, exacerbated by rising energy prices.

Even more damningly for “team supply-side factors”, Olivier Blanchard, using a super-simple New Keynesian type model, was able to correctly predict inflation in advance, just by looking at the size of Biden’s Covid relief bill in February 2021!

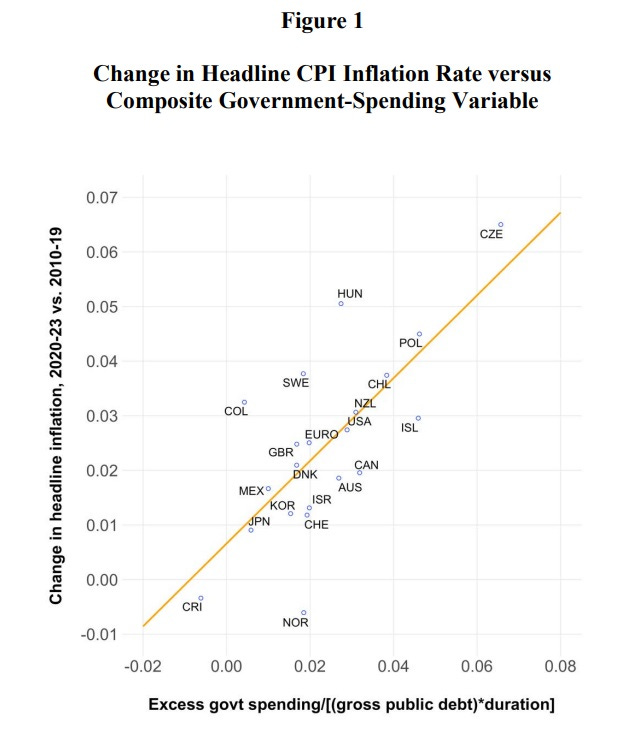

Meanwhile, Orszag’s chart of Covid stimulus vs. inflation includes a lot of developing countries, where inflation can often be very high due to a variety of factors that don’t typically crop up in rich nations. When Barro and Bianchi (2023) look only at OECD countries, they get a positive correlation:

And when Barro and Bianchi use an alternative measure of government spending consistent with the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level — the theory that says that government deficits cause inflation — they find an even tighter correlation:

I’m not sure whether limiting the analysis to OECD countries is the right thing to do, or how much we should trust in the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level. But this certainly shows that Orszag’s analysis is no easy slam dunk. Meanwhile, the plethora of studies finding a substantial role for stimulus in the inflation of 2021-22, and Blanchard’s successful ex ante prediction of inflation, are hard to ignore here.

I think it makes sense to conclude that Covid relief spending was one significant cause of inflation. Whether that was worth it or not is an entirely different question.

6. Am I wrong about national health insurance?

Via Marginal Revolution, I have found a paper that somewhat challenges my priors on the topic of national health insurance.

I’ve long been a proponent of national health insurance — not the “pay for everything and outlaw private insurance” thing that Bernie Sanders wants, but the more sensible Japan/Korea system, where the government pays 70% of everything and leaves the rest to the private sector. My reasoning is basically that there’s a lot of monopoly power pushing up prices in the health industry, and a government insurer that covered part of every procedure would have countervailing monopsony power that would be able to squeeze these excess costs out of the system. Basically, we already do a lot of this with Medicare, and it does result in lower prices:

Conservatives have often countered that this type of system would squelch medical innovation. I typically downplay such concerns, arguing that Japan and Korea exhibit pretty good levels of innovation. But a new paper by Yunan Ji and Parker Rogers is making me wonder if the conservatives’ concerns are more justified than I had realized. The authors look at what happens in various medical product categories when Medicare forces providers to cut prices. They find some pretty negative effects on innovation:

We investigate the effects of substantial Medicare price reductions in the medical device industry, which amounted to a 61% decrease over 10 years for certain device types. Analyzing over 20 years of administrative and proprietary data, we find these price cuts led to a 29% decline in new product introductions and an 80% decrease in patent filings, indicating significant reductions in innovation activity. Manufacturers reduced market entry and relied more heavily on outsourcing to other producers, which was associated with higher rates of product defects. Our calculations suggest the value of lost innovation may fully offset the direct cost savings from the price cuts. We propose that better-targeted pricing reforms could mitigate these negative effects. These findings underscore the need to balance cost containment with incentives for innovation and quality in policy design.

This is certainly a sobering result for proponents of national health insurance. But I’m not sure Ji and Rogers actually contradict my priors very strongly here. They argue that if Medicare only used its price-cutting power on products with very high profit margins, it could cut costs without hurting innovation:

In a well-targeted price reform, we would expect Medicare to prioritize product categories with the highest profit margins…[T]his analysis highlights that a more targeted approach could potentially reduce Medicare spending while minimizing negative impacts on medical innovation.

And this makes perfect sense with the theory of monopoly and monopsony. The monopsony power of a national health insurance system is a powerful and dangerous weapon — it needs to only be used in specific instances when there’s significant monopoly power that needs to be canceled out. You can’t just go clobbering every single product with price controls.

As always with activist government policies, the devil is in the implementation.

One thing to always keep front of mind when looking at medical innovation in countries with public health systems and price controls: whether or not the medical companies in those markets are selling into the US markets. I don't know the specifics about Japanese and Korean medical companies, but many European drug and medical device companies are essentially recouping all their fixed costs by selling into the US market, allowing them to sell at prices only slightly above their marginal cost in their home markets. US consumers wind up subsidizing much of the R&D for the entire world as a result, and if we imposed price controls on our markets, it would likely have catastrophic impacts for innovation in countries around the globe.

This is not necessarily an argument that US consumers _should_ keep subsidizing the rest of the world, mind you. But people have gotten so used to free-riding on the US medical system that I tend to think that they'd let innovation collapse before other countries would start picking up their share of the tab. As always, it's a lot easier to see money leaving your bank account right now than foresee the things that will never be developed because they could never be made profitable.

On #6, your first instincts are right.

There are two ways this paper is wrong.

1) The authors are ignoring a big facet of the world spending on health, the fact that the US has 4.23% of the world's population but accounts for about half of global health spending. The US shouldn't be doing this. We are a big market. Drug companies and Medical Device companies still launch products in the UK and Japan and Germany. We would still get innovative medicines even if we weren't paying out the nose for them.

The authors even acknowledge this on page 4, "The cost-conscious environment also altered market structure. The number of new entrants decreased by 40%, driven by a 72% decline in U.S. manufacturers’ entry, with NO SIGNIFICANT CHANGE among foreign manufacturers, perhaps reflecting their relative cost advantage."

Why do foreign manufacturers have a cost advantage? Because they are used to justifying the cost of their devices to national Health Technology Assessment agencies. Other countries have medical device companies that can innovate without a massive subsidy from the US taxpayer.

This is like your explainer on how important it is to make an industry that can compete internationally rather than relying on local government subsidies and captive market.

2) Let them eat R&D dollars!

Their "Our calculations suggest the value of lost innovation may fully offset the direct cost savings from the price cuts." is very misleadingly worded and framed. They are very strongly implying that the the "value of lost innovation, measured by reduced R&D expenditures, amounting to $2.9 billion annually following the price reform" (page 27) is comparable to "Medicare saved$ 3.8 billion annually in DME spending, adjusting for inflation." (page 28).

The "Value of lost innovation" is company spending on R&D. If Merck spends 10 million$ less on R&D in 2024 than it did in 2023, some people might lose their jobs and the medical research sector would shrink. There may be some long term effects on new drugs/devices but this is ultimately a kind of industrial R&D spending.

Conversely, if Medicare has 10 million$ more to spend, that's medical procedures, that's medicines, that is patient care, that is lives saved directly and immediately.

The authors word their comparison to make it seem like a dollar of lost R&D is doing the same thing as a dollar of lost Medicare spending, but it really, really is not.