At least five interesting things for the end of your week (#16)

Michael Lewis and SBF, how to win Cold War 2, American manufacturing, Target and shoplifting, and yet more on housing supply

I’m a bit overdue for a roundup, and lots of interesting stuff has been piling up!

First, podcasts. I have a new episode of Econ 102 with Erik Torenberg, all about the Israel-Gaza war. Here’s a Spotify link:

And here’s Apple Podcasts and YouTube. This was our most listened-to episode of Econ 102 so far, probably because people were paying so much attention to the new war. Anyway, the views I expressed on the podcast were a bit more wide-ranging and nuanced than the posts I wrote on the topic this week.

Meanwhile, on our latest episode of Hexapodia, Brad DeLong and I didn’t talk about the war at all. Instead we talked with our guest Brian Beutler, writer of the substack Off Message, about whether Democrats have been too wimpy and wonkish in recent years:

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things.

1. Michael Lewis was too nice to SBF

Michael Lewis has always been one of my favorite authors; I can only wish I had his generational talent for entertaining readers entertained with lifelike characters and gripping stories even as he teaches them actual useful information. Liar’s Poker was the quintessential story of the cynical, greedy turn in the U.S. finance industry, while The Big Short was the best chronicle of the madness leading up to the 2008 crisis.

But Lewis is now taking a lot of heat for being the closest thing that Sam Bankman-Fried has to a defender in the financial press. I haven’t read Lewis’ SBF book yet, but in recent interviews, Lewis certainly says things about SBF that are less negative than anything else I’ve read. For example, talking to 60 Minutes, Lewis said that he doesn’t believe that SBF knowingly stole his customers’ money. And in a recent Time interview, he asserted that the money was lost due to SBF’s “catastrophic sloppiness” rather than to deliberate malfeasance. When asked if SBF is a serial liar, Lewis hedges, calling him a “serial withholder” instead. When challenged to respond to criticisms that he got to close to the subject of his book, Lewis shot back:

This is what happens when you address a mob, is what it feels like…The anger seems, to me, to be like a separate force and part of American life right now, rather than something that's rational…Lord knows the very easy, lazy thing to do right now would be to throw Sam under every bus you could, and try to make him seem as bad as possible, because people respond to that. But it just wouldn't be true. It's not the character I knew. It's not the situation I knew…There’s a long history of people getting in trouble for books that are right, and the books end up being extremely valuable...And in this case, again, it felt like there's a tribe waiting that were natively hostile to the truth of the story I experienced.

I don’t have enough information to say Lewis is wrong here, but I expect when all is said and done, there will be solid evidence that SBF knowingly stole from his customers. In fact, I kind of doubt the standard story that SBF gave the money to his hedge fund and gambled it all away; I suspect he just embezzled most of it for himself, and still has most of it stashed in various places.

So my bet is that Michael Lewis is just being way way too nice to SBF here. But why? Lewis didn’t hold back when criticizing the bond traders at Salomon Bros. or the creators of mortgage-backed CDOs; why would he lob such a softball at a guy whose finance empire was infinitely more scammy than those others?

Maybe Lewis did get too close to his subject, or maybe the magic spell of cynical “effective altruism” that SBF and his cronies used to get on so many people’s good side. But I suspect that the deeper thing that’s going on here is that SBF, like so many crypto barons, presented himself as an anti-financier — a good guy taking finance back from the cynical Wall Street banksters who hustled everyone in the 80s and 90s and blew up the world in the 00s. In other words, SBF set himself up to be the antithesis of everything that Michael Lewis spent his early career bashing, when in fact he was just a far scammier version of the same.

The truth about the finance industry, I think, is that it’s been humbled significantly since the days of Liar’s Poker and The Big Short. The Dodd-Frank reforms and the tight regulation of systemically important banks, along with the aftermath of 2008 itself, really did make it harder to engage in financial shenanigans. Finance still makes a ton of money, of course, but its profit as a share of the total has fallen from over 30% in the early 2000s to around 18% today — barely higher than it was in the early 1960s.

The old Wall Street “masters of the Universe” have been humbled, and we don’t need the likes of SBF to rebel against them.

2. A great interview on national security threats

I don’t usually post video links, because they usually don’t have the high density of information that I prefer. But if you have the time, I highly recommend this video interview of Sarah C.M. Paine, a professor of strategy and policy at the U.S. Naval War College:

I have never seen someone speak so lucidly about such a wide range of national security topics. Paine knows her history incredibly well, and does an amazing job of boiling down the key principles for the audience. Dwarkesh Patel is an excellent interviewer, challenging Paine and pushing her to defend her ideas in a well-informed, thoughtful way.

Paine’s main message is that the U.S. and its allies possess very little power to affect the internal decision-making processes of Russia and China. We can influence their calculus from outside, but we can’t really persuade them to change their ideology or alter the structure of their internal politics. Thus, we must be prepared for Putin and Xi to make mistakes and to do things that hurt their own people, because these are the kind of leaders who sometimes do things like that.

Paine is also very explicit about what wins big wars like WW2 and conflicts like the Cold War: allies. No matter how powerful one country is, it can be beaten by a sufficiently large gang of other countries. So in preparing to resist Xi and Putin, yes we need military strength of our own, but it’s absolutely crucial that we get the rest of the world on our side. The Biden administration needs to hear this message, and the GOP really, really needs to hear this message.

Anyway, like I said, if you have a couple hours to spare, watch the whole thing.

3. America isn’t building enough, but we are building

I’ve repeatedly lambasted America for being the “build-nothing country”. Our lack of state capacity, our insane permitting system that allows NIMBYs to block everything, our complacent acceptance of cost overruns and delays, and other factors threaten to prevent us from building the green energy we need to decarbonize our economy and the high-tech factories we need to compete militarily with China. And we still see lots of stories coming out about how difficult it is to build things in America. Here’s the latest hair-pulling tale of woe:

A factory shortage is threatening the future of offshore wind in the United States, and few places illustrate the challenge better than an unfinished facility in upstate New York…Trees have been cleared for the facility, but almost three years after the factory was announced, construction on its five buildings has yet to begin. And the cost of the project has more than doubled from $350 million to $700 million.

There are various factors that contributed to this problem, but the main villain, as usual, is NEPA, the law that lets people sue any project to force it to complete cumbersome paperwork:

Progress has proceeded in fits and starts. Tree clearing prompted objections from some neighbors. A group of residents filed a lawsuit claiming the port had not adequately notified the public of its plans. It was later dismissed. While the project eventually succeeded in obtaining all the necessary environmental permits, costs have soared.

It’s becoming every clearer that it’s going to be very hard to revive U.S. industry — or accomplish progressives’ goal of decarbonization — without throwing NEPA under the bus.

But that said, America has thrown a lot of money at industrial policy, and it’s not all going to cost overruns or legal challenges. Battery manufacturing is up by almost 40% in real terms since the Inflation Reduction Act was passed:

My hope is that America’s initial struggles with industrial policy will cause us to course-correct, to find and eliminate the bottlenecks and roadblocks and inefficiencies, rather than to throw up our hands and retreat back to laissez-faire economics. If we can use the impetus of green industrial policy to reform laws like NEPA that block abundance on a wide variety of fronts, then so much the better.

4. Did shoplifting make Target close a bunch of stores?

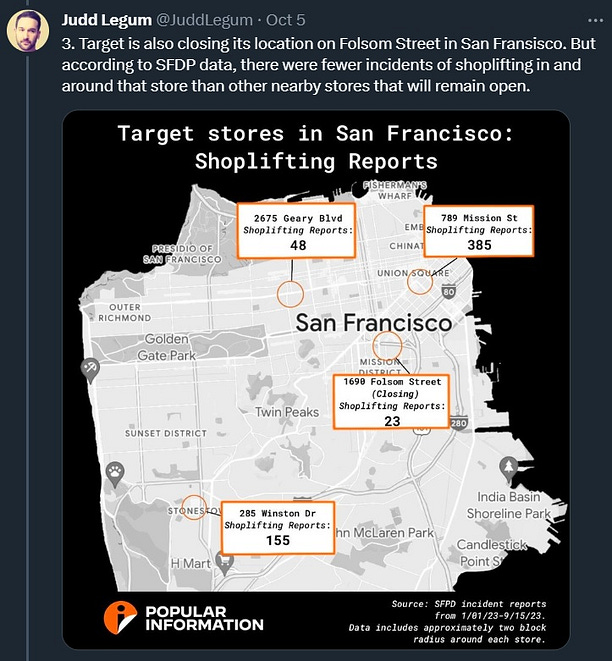

Target made a big stir a few weeks ago when it announced that it was closing a bunch of stores because of excessive shoplifting. The cities where stores were closed include San Francisco, Oakland, New York City, Seattle, and Portland. The reports fed a growing anxiety that tolerance of property crime is hollowing out retail in America’s progressive cities.

The blogger Judd Legum challenged Target’s claims, however. Analyzing police data, Legum found that there were fewer reports of shoplifting at and around the stores that were closing, as compared with other Target stores in the same cities.

Legum concluded that Target had other reasons for closing the stores, and was using shoplifting as a convenient excuse.

But while that might be true, critics were quick to point out that Legum’s data isn’t really reliable. Areas with lots and lots of shoplifting probably tend to report it less. In addition to “reporting fatigue” from huge numbers of incidents, there’s the fact that the stores that are closing tend to be in poorer neighborhoods, where police are less likely to care enough to respond to reports of petty crime. If the cops don’t care, why even report?

So Legum’s investigation should have also investigated the reliability of these reporting numbers. Data matters, but data quality also matters.

On top of that issue, there are at least two other reasons why Legum’s conclusion might miss the mark. First, there’s mitigation costs. Stores in high-shoplifting areas might put all their merchandise behind plastic cases and hire a bunch of security guards. That might prevent shoplifting, but at the cost of massively increased labor costs — security guard salaries, plus the fact that store employees are now required to assist customers with every purchase. If every store in an area is forced to resort to such costly measures, shoplifting might decline in the entire area, but the cost to some of the businesses might be ruinous.

Second, there’s a store’s ex ante profit margins to take into account. If a store in a poor area charges lower prices and makes lower margins, then it might not take as much shoplifting to force that store to close. In fact, shoplifting at other stores far away might even force a low-margin store in a poor neighborhood to close, simply by reducing the profitability of the entire company and forcing a round of cost-cutting that hit the stores in the poor areas first.

In other words, there are tons of limitations in the case Judd Legum is making here. He might be right, but there are a lot of things he didn’t take into account, so I’m not sure we learned a lot from his data-gathering exercise.

5. More anecdotal evidence on market-rate housing construction

As you know, I love citing evidence that building market-rate housing lowers rents. I would also love citing evidence to the contrary, if it existed, but there’s just not a lot of it — pretty much every careful scientific study and anecdotal urban experiment reiterates the conclusion that supply is effective in lowering rent.

First, we have a report from Jay Parsons, an economist who studies rental housing. He finds that in areas with lots housing supply, rents for mid-market apartments go down the most, even if it’s high-end apartments that are mostly getting built. The reason is that when you build fancy luxury apartments, a lot of people from the mid-market move to those nicer, newer apartments, leaving a glut of supply that pushes rent down. Here’s his chart:

This is pretty much exactly what I predicted in my post about “yuppie fishtanks”. When you build nice apartments for yuppies, they move into those nice apartments, and stop trying to outbid regular middle-class folks for the older mid-market units.

And then we have Oakland, which has been on a building spree, and where rents have fallen by 7.2%. This could be caused by other factors, of course, such as Oakland’s crime wave, which could be making the city less desirable to live in. But similar crime waves in other Bay Area towns haven’t led to similar drops in price, so maybe it was all the housing Oakland built. In any case, it seems encouraging enough to try similar construction sprees elsewhere.

I had the same idea on Lewis and made a comment to that effect on Molly White's excellent crypto blog (newsletter.mollywhite.net). It's really the classic phenomenon in our culture - and all of human history - of the enemy of my enemy being my friend. Lewis seems like such a clear case of it, but you can see it in the people who had reasonable critiques of 'wokeness' but then fell down a rabbit-hole of insanity, all sorts of conspiracies, negative polarization on Ukraine, etc., etc, etc. ad nauseam.

In the podcast, Noah Smith's analysis of the trends in military technology strikes me as spot on. But I would push back against his insinuation that America's military budget is too small. It is just massively misallocated. We are spending way too much on machines that are big, costly, dumb, and vulnerable. We are spending too little on stuff that is small, smart, cheap, and disposable.