America's supply chains are a disaster waiting to happen

A guest post by Yann Calvó López and Ben Golub.

One of the big themes of this blog is New Industrialism. Supply chains are an important part of that. The pandemic, and the inflation of 2021-22, gave America a taste of how painful it is to have our supply chains disrupted. And yet once the disruption eventually ended and supply chains normalized, we seemed to forget all about the problem — even though even greater disruptions from geopolitical conflicts might be looming on the horizon.

We need to think more systematically about the economics of complex supply chains — what Bill Janeway calls “mesoeconomics”. So here’s a guest post by Ben Golub and Yann Calvó López on the topic of supply chain vulnerability. Calvó López is a Research Associate at Northwestern University. Golub is Professor of Economics at Northwestern whose research focuses on social and economic networks. They would also like to express their gratitude to Matthew Elliott of Cambridge for conversations and collaborations that have been pivotal to developing the ideas in this piece.

The guest post is very long, so it’ll be published in two parts; part 2 will be published tomorrow.

A union representing 85,000 US dockworkers—spread across 36 US ports on the East and Gulf Coasts—will start the largest shipping strike the country has seen in nearly 50 years if a deal isn’t reached by Tuesday. Ports and other infrastructure are getting congested as importers scramble to reroute their goods.

Experts predict that the consequences will be severe, retracing the steps of the pandemic-induced supply chain chaos of 2021–2022. Container traffic jams will bring ports to a standstill, shipping prices will spike, and many retailers will ultimately be left out of stock for the holidays. The consequences for US commerce will reverberate for years, likely reawakening inflation.

This is just the latest in a series of supply chain disruptions over the last three years—the last one being the ongoing shutdown of Red Sea shipping due to war in the Middle East. In some cases, supply chains have adapted successfully, while in other cases their fragility has led to lasting scar tissue. Rising geopolitical tensions across the Pacific threaten to test the fabric of world commerce more severely than anything we have seen yet.

This raises some pressing questions about the economy. When is the world’s network of supply chains fragile, and when is it resilient? Researchers have made surprising discoveries about how supply networks break down and what keeps them healthy.

In this two-part series of posts, we distill some of the lessons for businesses and policymakers interested in preparing for and responding to the increasing risks. We close with an argument that the impact on supply networks should be perhaps the main economic consideration as the risk of a US-China confrontation rises.

1. Container Chaos

The 8% inflation rate in the US in 2022—a figure not seen since the 1980s—has upended American politics.1 It has also been a constant source of headaches for businesses. A year prior, the global automotive sector lost $210 billion in sales in a single year – over half of typical annual profits,2 with industry giants such as General Motors temporarily halting most of their North American plants due to shortages. By September 2021, the cost of shipping a 40-foot container from Shanghai to Los Angeles was up a staggering 1,110% since early 2020. Two months later, 111 ships carrying tens of billions worth of goods formed an unprecedented queue off the California coast.3

These distinct disruptions were causes, symptoms, and consequences of strained global supply chains. Our reliance on the proper functioning of the globe-spanning web of supply relationships became painfully evident when this network seemed to falter. Indeed, supply chain problems are arguably a significant reason for advanced economies being supply-constrained, a concern that is occupying the minds of economic policymakers at the highest level.4

The CEO of Flexport, Ryan Petersen—one of the few public commentators who could explain the pandemic supply chain crisis as it unfolded—believes that many of the same patterns will play out again if the dockworkers go through with their strike. So it’s worth reviewing the basic mechanics of that crisis.

They can be traced back to the early days of the COVID-19 outbreak, which brought about an abrupt change in consumer behavior in rich countries: consumers staying home shifted their spending from services to tangible goods—treadmills, new TVs, home office chairs.5 This sudden surge in demand, particularly in online shopping, caught supply chains off guard.

The growing international fragmentation of production over the last few decades meant that the shock was a global phenomenon, with shipping at the center of it.6 Ports in the US found themselves overwhelmed with factory goods, leading to queues of dozens of ships. Unclaimed containers accumulated at ports; a shortage of truck drivers dating to before the pandemic meant that many of those containers couldn’t swiftly be transported to warehouses. More generally, labor shortages plagued the logistics industry, worsening congestion issues. With many of the ordered goods—alongside hundreds of tons of personal protective equipment—coming from China, an imbalance in global trade flows led to a critical shortage of shipping containers in Asia.7 Freight rates subsequently skyrocketed.

The consequences of this logistical mess rippled throughout the economy. Shortages disrupted industries worldwide. Shipping became existential for many firms, so they were willing to pay ever more to get their supplies—in other words, shipping demand was highly inelastic. This caused prices to climb sharply—both for transportation and manufactured intermediates. Lower-margin businesses were eventually priced out of shipping entirely—which was necessary to relieve the strain, but exacerbated shortages. Taken together, the crunch fueled an inflationary trend whose reverberations are still with us.

2. The Missiles and the Cape

The post-pandemic strain on global supply chains exposed their fragility. The disruptions caused by the Houthis underscore that they remain vulnerable.

Fast-forward to June 2024. The Tutor, a Greek-owned coal carrier sailing 126 km off the Yemeni city of Hodeidah, is hit by a missile and a naval drone. Severely damaged, it sinks six days later.

More than 190 similar attacks have been carried out by the Houthi, a politically motivated military militia based in Yemen, since October 2023. Though few of these attacks cause as much damage, they are very effective in a different way: They are effectively blocking one of the arteries of world commerce. In February 2024, traffic through the Red Sea – which typically channels 30% of global container shipments – was down 90% from its December 2023 levels, and the crisis shows few signs of easing.

Major shipping companies are taking the long way around, quite literally. They are rerouting their vessels around the southern tip of Africa, via the Cape of Good Hope route, adding about 20,000 km to each journey.8 That isn't just a longer trip—it's an additional $1 million in fuel costs per ship for each one-way voyage. It also means a significant reduction in shipping capacity.9

Given the highly inelastic nature of demand for freight, shipping prices – once again – soared.10 Beyond the cost increases, importers, facing uncertainty and fearing congestion, are ordering early and increasing inventory, potentially overwhelming major ports and exacerbating the very congestion issues they're trying to avoid. This has raised renewed fears of high inflation, even before the port strike loomed.11

The post-pandemic strain on global supply chains exposed their fragility. The disruptions caused by the Houthis underscore that they remain vulnerable. And the most dramatic test of whether they can stand up to strain is likely to come from rising geopolitical tensions even larger than those in the Middle East.

3. The Next War

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine showed that wars waged for territorial expansion are not a thing of the past. It shattered not only the security assurances Ukraine had received from great powers12 but also the post-World War II international order.13 With it, the prospect of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan—a threat decades in the making—looms larger. Beyond the profound political and humanitarian implications, the threat of a new age of war also has an economic dimension: the prospect of damage to supply chains that would make the Houthi attacks in the Red Sea look like a minor inconvenience.

The stakes are high. As of 2023, a single Taiwanese company, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, or TSMC, was responsible for manufacturing more than 60% of the global supply of semiconductors and over 90% of the highly advanced ones. It is the biggest manufacturer supplying NVIDIA. A disruption of the $618 billion14 Taiwanese semiconductor giant would have serious implications for the world economy, more so given the highly customized nature of the industry.

The threat has already manifested in one of the crises we have mentioned. Pandemic-related semiconductor shortages in 2021 had widespread impacts on a range of industries. Beyond the automotive industry, Apple reported a $6 billion loss in sales due to chip shortages in October of that year. Sony’s supply struggled to meet the demand for the PlayStation 5s. According to an analysis by Goldman Sachs, the semiconductor shortages impacted as many as 169 industries. Pat Gelsinger, CEO of chipmaker Intel, put it simply: “Every aspect of human existence is going online, and every aspect of that is running on semiconductors.”

Governments are taking these threats seriously. The European Union accelerated a push to wean itself off Russian energy. The United States invested $280 billion through the CHIPS and Science Act, aimed at decreasing dependence on East Asian semiconductor supply chains. And many Western policy discussions increasingly focus on economic decoupling from China.

Policymakers now care about the risks associated with the supply network disruptions of the future, and the role policy can have in mitigating them. The task facing economists is to dissect the functioning of global supply chains, pinpoint their weaknesses, and understand what it takes to make them strong.

Even the terms we use in talking about supply chains show that our thinking about them is still not adapted to the challenges the world faces.

Examining individual cases of supply chain disruptions, however, can only take us so far. To answer these questions, we need an economic understanding of supply chains as mature as our understanding of interest rates or tariffs. However, the economics of complex, modern supply chains is a surprisingly understudied area.

4. The Web We Weave: Unraveling Global Supply Networks

Even the terms we use in talking about supply chains show that our thinking about them is still not adapted to the challenges the world faces.

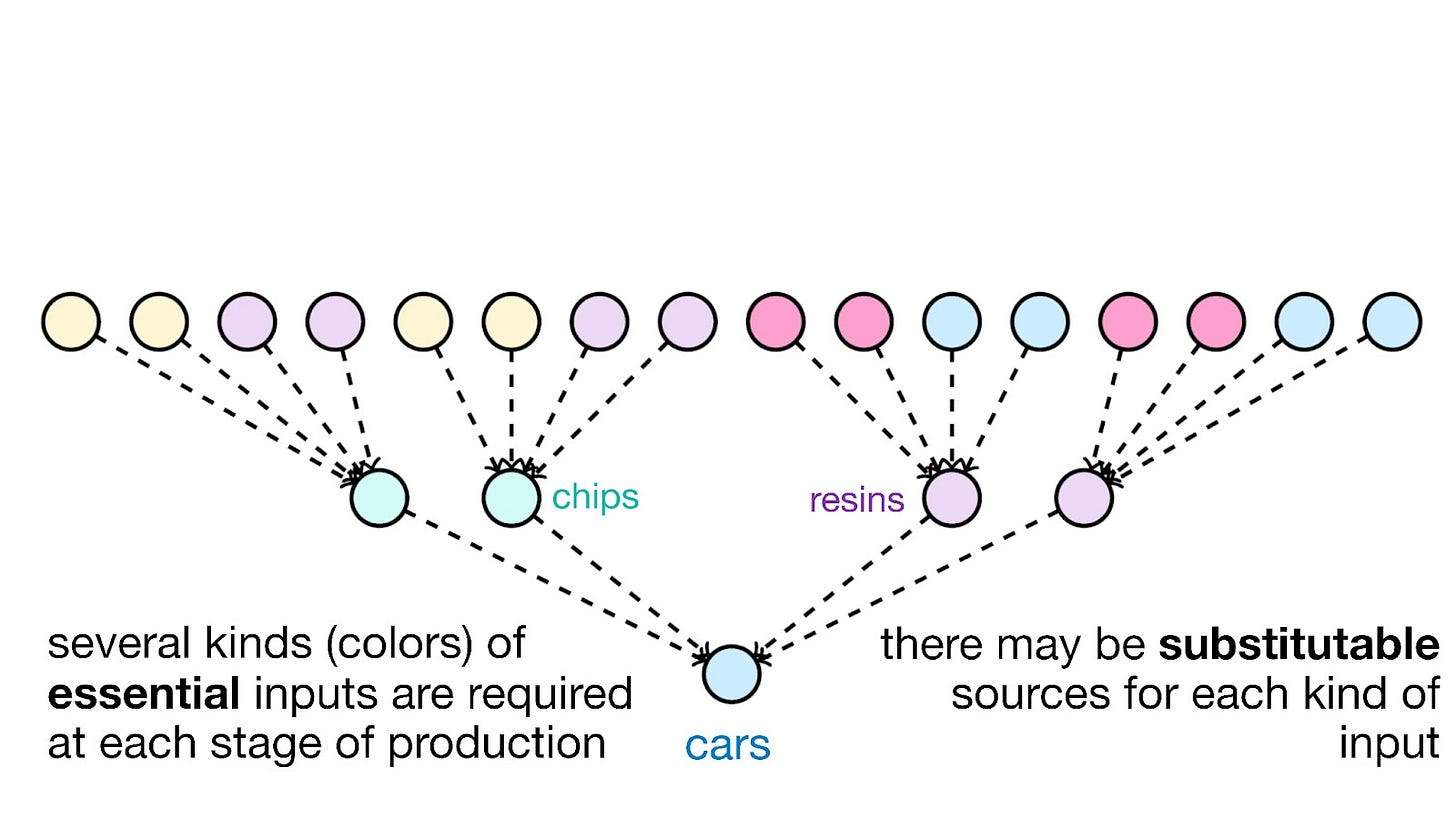

“Chain” suggests a simple, linear progression from raw materials to finished goods. But this picture is inaccurate. The system of business relationships that supports production is better thought of as a web. Think of firms as nodes, or points in the network. They are connected through their sourcing relationships—known as links. These relationships are directed—inputs go from the supplier to the buyer, which we depict with an arrow in that direction. Some firms require highly specialized inputs that can only be provided by specific partners, while other businesses can source more generic inputs from a variety of suppliers. A given firm’s supply network can have many tiers—that is, a firm’s direct suppliers may themselves rely on other suppliers, creating multiple layers of interconnected firms, stretching far upstream15 in the production process.

For a real-world illustration, consider Toyota's supply network, which the company mapped out following the disruptive 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. By examining up to ten tiers of suppliers, Toyota discovered their production relied on a staggering 400,000 items sourced directly or indirectly. This highlights the vast branching and complexity that emerges when we look beyond the misleading linear structure implied by the term "supply chain".

The web we have described can be thought of as the tissue connecting firms. Crises occur when parts of this tissue are disrupted. Links are disrupted when firms cannot successfully trade or work together with their suppliers due to issues such as shipping problems, trade barriers, or contract breakdowns. Disruptions can also happen to businesses themselves—the nodes in the network. For instance, a business may temporarily fail to produce due to natural disasters, strikes, or financial problems. We can picture such disruptions as some links or nodes turning off or being closed, just as a road or an intersection in a road network might be closed. The impact then ripples outward.16

Once we have this conceptual framework, we can talk about two kinds of threats to the fabric of global supply networks.

5. The Diversification Mirage

Like a river tracing back to a single spring, a shock upstream can make entire industries run dry.

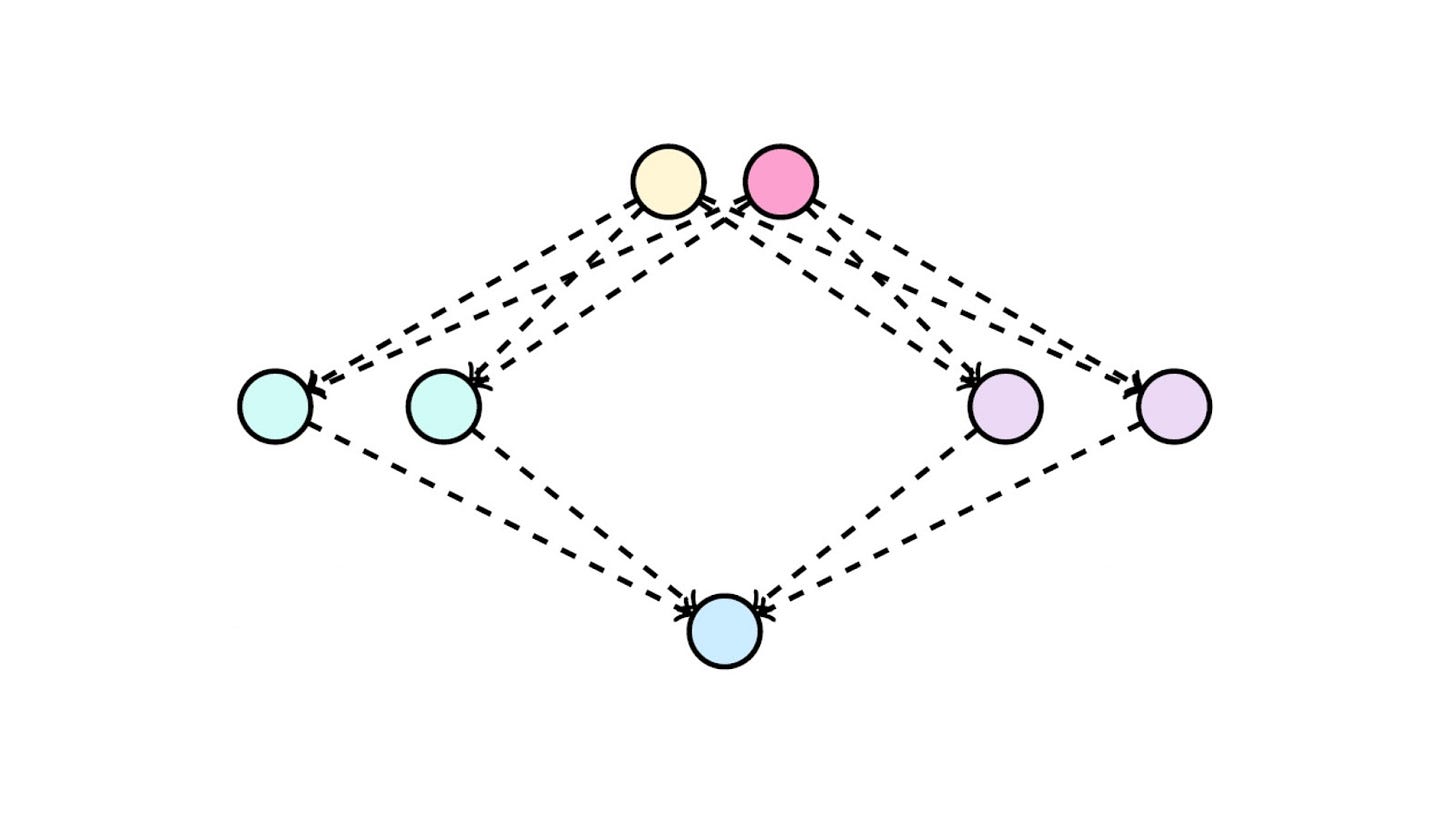

The most intuitive type of vulnerability in modern supply networks is concentrated dependence—where a significant portion of production relies on a small number of firms or a specific region. Crucially, it can impact firms or sectors whose production seems well diversified—but who ultimately depend on the good functioning of a handful of firms. This phenomenon can be illustrated graphically by a diamond-shaped network.

Concentrated dependence can create a precarious situation where a localized shock, such as a natural disaster or even a single firm's disruption, sends far-reaching ripples throughout the economy.

Picture a city where most of the traffic between two major districts funnels through a single bridge. Just as a traffic jam at the bridge can paralyze the entire city's transportation, a disruption at a key supplier or region in a diamond-shaped network can halt the entire supply chain.

The 2011 Thailand flood provides a stark example. Considered the country’s worst flood in modern history, it lasted from July to November of that year, affecting over 13 million people. While Thailand was not a major manufacturing hub itself, it was a critical supplier of components for the auto and electronics industries. The floods disrupted production at factories owned by Western Digital, Toshiba, and others, creating global hard drive shortages. Prices of hard drives spiked 15-40%, and major customers like Apple, HP, and Dell faced supply issues. The impact was disproportionate to Thailand's direct role because of the underlying supply concentration.

Similarly, Taiwan's dominant position in advanced chip manufacturing, which we have already discussed, means that any disruption there, whether due to a natural disaster or geopolitical tensions, could cripple industries worldwide.

Like a river tracing back to a single spring, a shock upstream can make entire industries run dry.

Why, then, does concentrated dependence arise in the first place?

One big reason is that, for a given tier, the lowest-cost, most productive suppliers are sometimes all concentrated in a single region. Such concentration of suppliers can result from the well-documented phenomenon of agglomeration externalities: The concentration of firms in a single location leads to shared access to specialized labor markets, suppliers, and industry-specific information. Agglomeration facilitates knowledge spillovers and expands the talent pool, thereby fostering productivity.17

A second, related reason for concentrated dependence is that using multiple products and services from a single supplier, or from nearby suppliers, reduces transportation and coordination costs—a phenomenon known as economies of scope in sourcing. In Shenzhen, China, for example, technology companies like Huawei can source many of their inputs from a dense ecosystem of local specialized suppliers that produce a wide array of electronic components.

While they enhance efficiency in some ways, these practices can inadvertently lead to fragile diamond-shaped networks and create major risks for firms further down the supply chain that may be oblivious to these vulnerabilities.

6. The Complexity Trap: Gumming Up the Works and Bringing a Network to its Knees

Concentrated dependence presents obvious risks. It's tempting to think that highly diversified supply networks, without upstream concentration, are inherently resilient. Imagine a manufacturer with a complex, multi-tiered supply network. Each business in the network sources from many suppliers across various countries—each of which, in turn, has its own diverse set of suppliers. The businesses are sophisticated, securing multiple potential options for each critical input to insure against the risk of disruption to any given relationship. This highly diversified, expansive type of network is certainly able to withstand localized shocks—if a few suppliers anywhere in the network fail, the network has ample ways to work around the shock. Indeed, we might be tempted to say such a network is inherently robust.

This optimistic view is wrong. Such a system can also fail dramatically, but its characteristic way of failing is quite different. It breaks down when the performance of many firms or relationships is degraded at once, even if that degradation is moderate in severity. The COVID-19 disruptions we have discussed above provide a clear example: port congestion and general stress on the logistics system affected a significant proportion of links, even those unrelated to the initial demand spike.18 Though there was no single region or product that all the problems traced back to, the accretion of damage caused a significant economic crisis. This is also the kind of damage we expect if the port strike materializes and disrupts shipping throughout the US economy.

This kind of disruption is harder for most people to think through than the harm of concentrated dependence. Most of us don’t have great intuition for what it means to gum up the works of the kind of network we’ve just described—even those of us who think about such things for a living! But, following the substantial impacts of the pandemic-related supply chain disruptions, recent theoretical research has uncovered how large, diversified supply networks can be brought to their knees by such shocks.

To get some idea of this sort of phenomenon, imagine a large city, such as New York or London, with many alternative connections between places—analogous to the substitutable sourcing opportunities of various firms. Now imagine that the performance of all these links degrades: rolling power outages cause traffic lights to fail at every intersection at different, random parts of the day, say an hour or two. Meanwhile, flooding makes some city blocks impassable. The combined effect of all these small individual disruptions could be enormous. Cars would pile up around disrupted places in the network, which would increase the load on nearby ones, making the congestion even worse when some of those failed. We would not be surprised to see citywide gridlock and much longer travel times—even though in isolation no single traffic light breaking for part of the day presents much of a problem. And the denser and more heavily loaded the city streets are, the worse it would be.

The science of complex networks studies such situations. One important discovery that has been made over and over again (in various guises) is that of phase transitions. At a certain level of global (that is to say, widespread, as opposed to localized) disruption, the behavior of the overall system changes drastically—as drastically as water freezing into ice. In our road example, this might look like the sudden appearance of gridlock once the disruptions affect enough roadways and intersections. In supply networks, it looks just like the headlines of 2021.

7. Nobody’s in Charge

The price mechanism coordinating the activities of a system without central management is one of the greatest achievements of human civilization. But systems often do not run successfully if left to be managed only by the invisible hand of the market.

When we see such failures, we’re tempted to ask what was mismanaged and who messed up. This leads us to the question of who is in charge of managing the system in the first place. Unlike traffic lights and road networks, which are typically under the management of municipal authorities, no authority is in charge of the overall workings of the global supply network, or—at least in most countries—even any single nation’s piece of it.19

Is this good or bad? Is it a problem that we run supply networks like this?

In economics, sometimes it’s fine that nobody is in charge. Nobody is in charge of the bakeries in London—beyond basic regulations such as health codes—but the market manages to provide a reliable and varied supply of baked goods nevertheless. Other times, as with road networks, central coordination and management are needed to make things work.

What distinguishes these two cases is that in the case of the bakeries, the types of price mechanisms and contracts that exist seem to be effective at transmitting incentives across the various businesses in the system. For example, when eggs are scarce, their price goes up and suppliers of eggs are more motivated to produce more and fill the gap. At the same time, some bakeries produce fewer products with eggs, leaving more eggs for others who really want them. So there’s no need for anybody to oversee the whole operation.

The fact that prices can achieve this kind of decentralized harmony does not imply that they always do. We could imagine trying to manage the road network in a similarly decentralized way. Individual stretches of road could be operated by separate businesses, in a market system. Each business would be responsible for doing its own maintenance. The operators could charge users directly via electronic tolls—or they could have a claim on a city’s tax revenue. We suspect that this wouldn’t work very well, and that there are reasons why very few places run their roads like this. To take just one example of a problem with this approach, if a whole road network comprising many separate businesses fell into disrepair, people would avoid an area altogether, and no single road operator could attract business by cutting prices or keeping its own road in good shape.20 For this and other reasons, such systems make more sense to manage more centrally, or at least with a lot of regulation and coordination.

The price mechanism coordinating the activities of a system without central management is a wonderful miracle when it works, and—without exaggeration—one of the greatest achievements of human civilization. But systems—especially complex ones—often do not run successfully if left to the invisible hand of the market. Often, a guiding external hand of coordination or support by public institutions is needed.

Economists are coming to agree that today’s complex supply networks are closer in many ways to the situation of the roads than the bakeries.21 Picture a firm producing an intermediate good, such as semiconductor components. Suppose it decides to invest more in its own sourcing reliability. Examples of such investments include building stronger relationships with its own suppliers of raw silicon wafers, opening plants in diverse locales, and improving its enterprise resource planning systems, which make the business more capable of anticipating and reacting to disruptions. These actions boost the reliability—and, consequently, the profitability—of its entire downstream supply chain. But the profits it makes in doing this will typically be only a fraction of the value it creates with these investments—for consumers and for other businesses. So the business will tend to underinvest in robustness relative to what is best for the network as a whole.

Even when businesses try to optimize their investments by looking deep into their supply networks and coordinating with one another, the complexity of extensive, diversified supply networks creates major challenges. Tracing—let alone addressing—the causes of shortages and delays becomes a daunting task when they originate from multiple tiers away.

This does not mean, of course, that we would be better off if some authority tried to manage the production of complex goods centrally, as if the world economy were one city’s road network. Fortunately, there is no need to choose one extreme—totally decentralized operation or full central planning. Interventions—by governments and industry groups—can make supply networks much more robust than they would be otherwise, in a market left alone to coordinate itself. Or, at least, the research we have so far tells us there are some good reasons to believe this is so, and no fundamental economic law that tells us otherwise.22

However, before we think about what we can do to strengthen supply networks, it’s worth recognizing that sometimes economies can be amazingly adaptable in the face of crises all by themselves.

In the next post in this two-part series, we will look in detail at one such success story. We will examine lessons for business and policy: what economics can teach us about keeping supply networks robust and healing them when they fail.

Note: Part 2 of this post can be found here:

Respondents of two recent surveys conducted on representative samples of the US population highlighted their strong aversion to inflation, irrespective of the growth it might be associated with.

Based on an approximation from the trade publication FreightWaves.

As Noah Smith put it in a recent commentary, a world of supply constraints is essentially one in which “demand stimulus and job provision programs can easily stoke inflation,” since the economy finds it hard to expand its production on demand.

An economic commentary by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland investigates the increase in spending on durable goods during the pandemic and its determinants

In the past few year, economists such as Pol Antras have been studying so-called Global Value Chains – the increasing international fragmentation of production. Contemporary supply chains typically spread across many countries. Indeed, world trade in inputs – i.e., in resources used to create goods and services – now overshadows that of final goods: It is estimated that input trade accounts for two-thirds of world trade.

See the following article by the New York Times for a useful visualization of how the pandemic supply chain crisis unfolded.

For example, on one day in January, 95% of container ships that, in normal times, would have transited the Red Sea were going around Africa instead. Insurance costs, meanwhile, had risen more than threefold since the start of the attacks.

Flexport CEO Ryan Petersen estimates that “it [now] takes 30-40% longer to complete the round trip from Asia to Europe, lowering the network's effective throughput.”

“The simplest answer for why prices are surging is that freight is one of the most inelastic markets in the entire global economy—brands rarely ship more stuff just because … freight is cheap, or less stuff because… freight is expensive.’’ Ryan Petersen (May 20, 2024)

“Relative to what would have happened otherwise, we will see higher inflation, higher mortgage rates and lower growth. [...]This shock is not going to be as big but it is unfortunate." Dr Mohammed El-Erian, chief economic adviser at Allianz.

In 1994, in return from transferring its nuclear warheads to Russia for elimination, Ukraine received security assurances from the latter, as well as from the UK and the US. They were not to use economic coercion or military force against Ukraine, "except in self-defense or otherwise in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations.

As of the 6th of September, 2024.

Upstream operations refer to the stages closer to initial stages of the supply chain (raw materials), while downstream operations refer to the stages closer to or at the final stages of the supply chain.

Economists have incorporated economic shocks into models of globalized supply chains. (e.g., see papers by Pol Antràs and Davin Chor on Global Value Chains, by Chad Jones on the importance of intermediate goods and by Emmanuel Farhi and David Baqaee on the macroeconomic impact of microeconomic shocks in production networks). But most of the resulting models, while useful, are based on prices and sourcing decisions re-equilibrating after shocks, Economists are only beginning to grapple with what happens when shocks genuinely disrupt production in the short run.

Silicon Valley is perhaps the most renowned example of agglomeration externalities. Tech firms, from giants like Apple and Google to startups, benefit from a concentration of specialized talent, suppliers and services, and similar companies, creating a self-reinforcing ecosystem that drives productivity and innovation.

For instance, 2021 and 2022 saw shortages of products ranging from automobiles and medical supplies to construction materials, metal cans, and Grape-Nuts cereal.

When the COVID supply chain issues hit, the Council of Economic Advisors wrote that the White House had “established a Supply Chain Disruptions Task Force to monitor and address short-term supply issues.” The ad hoc nature of this response is one way to see that none of the economic agencies of the US government were closely monitoring the state of the supply network in their routines.

There are other problems that take us a little more into economic theory. Road operators that own the best way to get between two places would have incentives to charge prices that are too high (monopoly distortions). If there were several such operators owning the route, prices would be even more inefficient due to double marginalization. There are also economies of scale and scope in road operation: maintenance, for example, is much easier to plan and perform when one operator is in charge. Otherwise, adjacent operators have to negotiate over the disruptions of repairs, which wastes time and effort. In short, road operation is probably a “natural monopoly,” which means that it is efficient to run it centrally within a given locale.

For two examples of very recent arguments made in favor of this view in the research literature, see "Supply Network Formation and Fragility" (2022), by Elliott, Golub and Leduc, and "The Macroeconomics of Supply Chain Disruptions" (2024), by Acemoglu and Tahbaz-Saleh.

A few economists afflicted with “complete markets brain” might still reach for the intuition of the First Welfare Theorem—the idea that (under certain conditions) markets allocate resources in private production efficiently, with no room for improvement through investments by the government. This perspective is mistaken because to make markets rich enough to price the risks involved, there would have to be financial assets allowing firms to bet (or buy insurance) indexed to a huge variety of risks, and these markets don’t in fact exist. Most recent theoretical research on pricing in supply networks takes the perspective that missing markets and the resulting distortions are a very important part of what keeps supply networks from efficiency.

If the US can’t make: transistors, resistors, capacitors, magnetic motors, VLSI chips, batteries, wiring and PCBs onshore then we are toast. Fundamental electronic component manufacturing is key to drones, robotics and autonomous weapons systems. Lose the ability to directly manufacture those and then the loss of access to Chinese markets due to a war in Taiwan and game over. Eighteen months of the loss of those supply chains and the U.S. can’t build missiles or anti-ship weapons etc. game over and we only have our aging nuclear fleets to defend us.

Economics is making progress. Rules matter. Institutions matter. Supply chains matter. They haven't quite traced the supply chain back to the earth yet. The start of every supply chain is nature, Creation, the natural world, ecosystem goods and services. An economy grown out of scale with the planet is going to suffer shortages. Or collapse when things run out.