Americans are falling out of love with the idea of college

We expected too much of our one functional institution.

I remember, when I graduated, there was this guy I knew who was very disappointed with his university experience — so disappointed that he made us all listen to a poem he wrote about it. The poem was very bad (yes, it rhymed “knowledge” with “college”). Afterwards, I said to him “Man, I think you just expected too much out of this institution.” When I see the latest piece of news about Americans’ dissatisfaction with their university system, I think back to that guy’s poem, because I think maybe we all expected a little too much out of our universities.

In the 2000s and 2010s, many American institutions seemed to creak and fail. The financial system blew up. Health care became impossibly overpriced. We stopped building houses, we stopped going to church. The government was paralyzed by polarization and populism. But our higher education system remained the most respected in the world, with international students beating down our doors to get American diplomas. College towns flourished even as the Rust Belt and the Great Recession laid waste to the rest of small-town America. And as the opioid epidemic raged and suicide rose, college seemed like the one force that could actually teach Americans to live healthier lifestyles. In a nation where everything seemed to be going wrong, we put more and more faith in the shining beacon of our one functional institution.

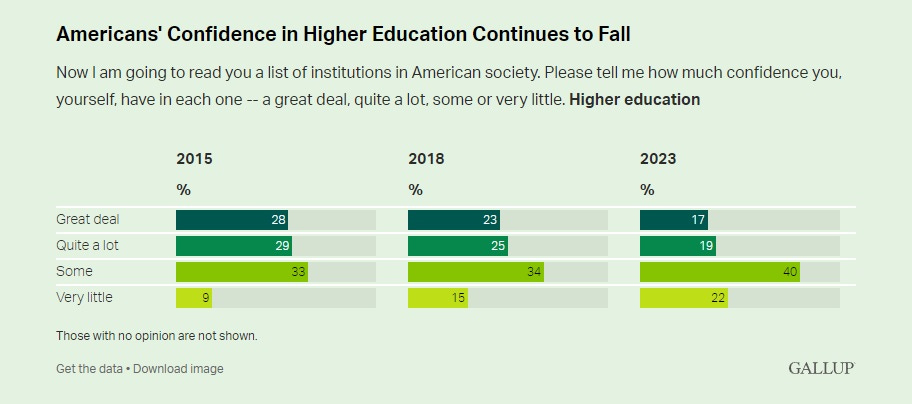

Now, years later, that faith appears to be waning. Recent polls show a very sharp drop in Americans’ confidence in higher education:

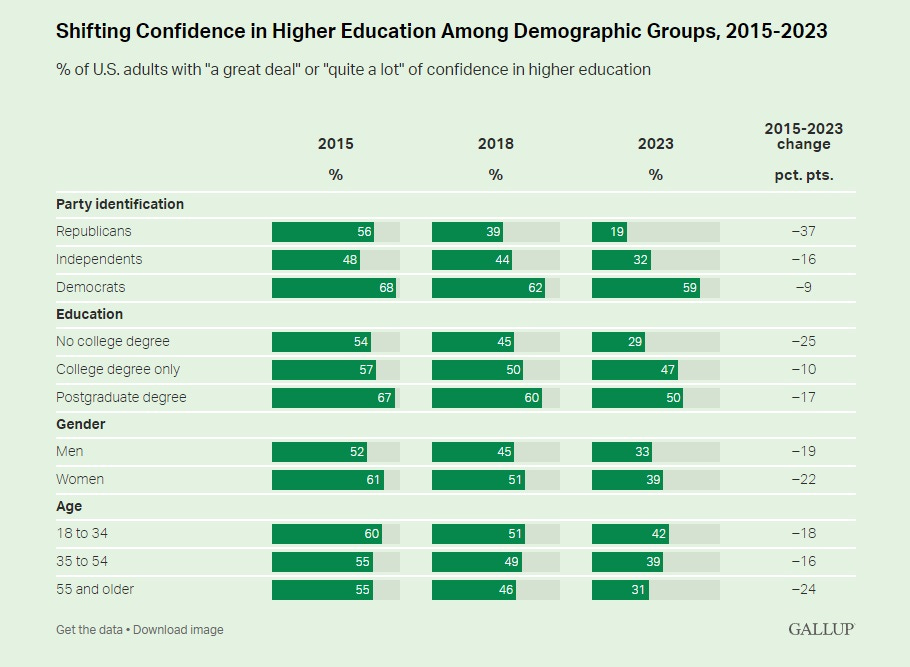

The shift is more pronounced among Republicans than Democrats, but it’s present for basically all demographic groups; this isn’t just politics. The drop in college’s favorability is slightly stronger among the young relative to the middle-aged, among women relative to men, and among people with postgraduate degrees relative to those with just a bachelor’s.

Other polls find similar results.

In general, Americans are simply falling out of love with the idea of college. Why? Maybe part of it is a lingering effect of the pandemic school closures, and maybe part of it is just the general era of social unrest and negativity that we just experienced. But it’s not just polls; trends in “harder” measures like enrollment, tuition, and choice of majors all seem to point in the same direction.

My read of the situation is simply that Americans are coming to the same basic realization that my poetically challenged classmate came to: College isn’t a magical box that will make your life turn out like a fairy tale. We inflated our expectations of what this one institution can do for us, and now we’re suffering from the inevitable disillusionment.

Why young Americans are starting to turn away from college

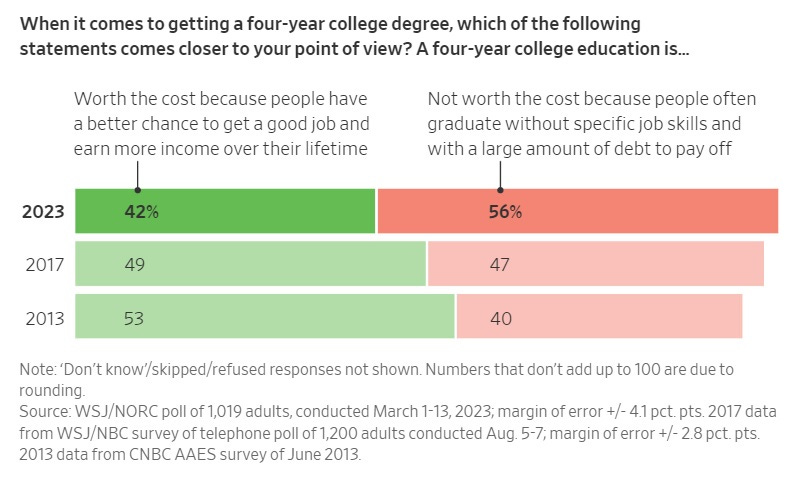

A recent WSJ poll points to the reason that young Americans are less positive about college: Increasingly, they just don’t think the economic payoff is worth the money.

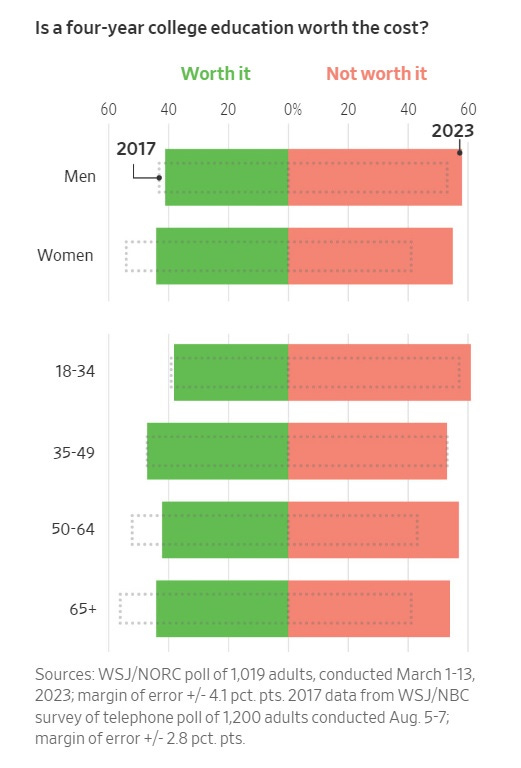

This negative attitude is more common among the young:

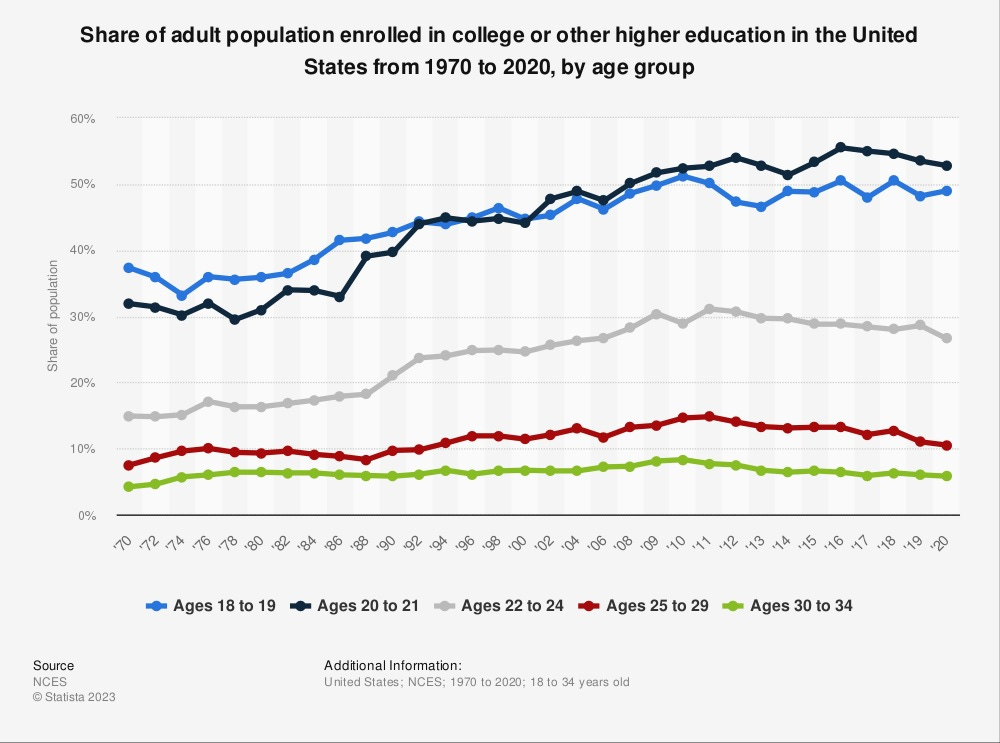

Students aren’t just telling negative stories to pollsters; they’re voting with their feet. Even before the pandemic, college enrollment had begun to fall steadily.

The drop is concentrated among students at 2-year colleges, but this is exactly what you’d expect; those are the most marginal students, who will probably benefit the least from their degrees. When we’re talking about supply and demand, change happens on the margins.

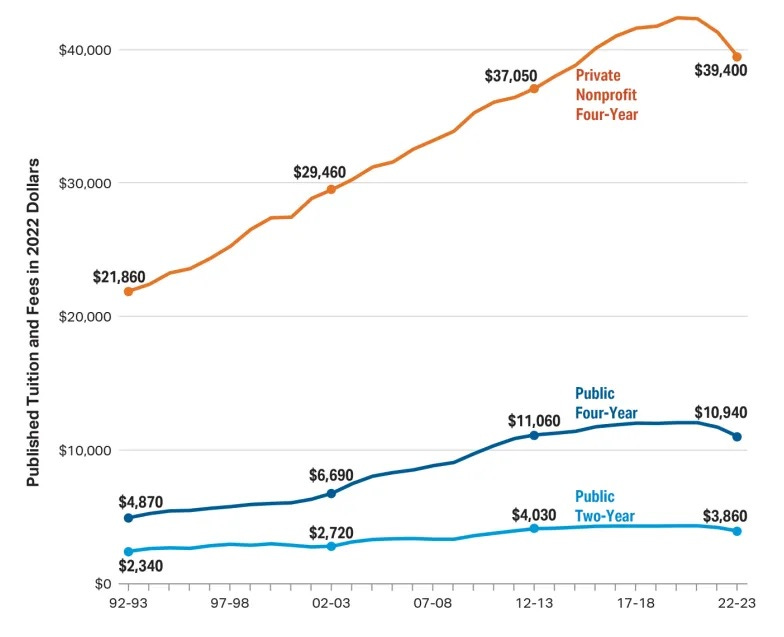

There’s another sign of falling demand, too: falling prices. Tuition, which seemed like it would never stop skyrocketing, suddenly plateaued and started falling in inflation-adjusted terms — even as prices for other services rose.

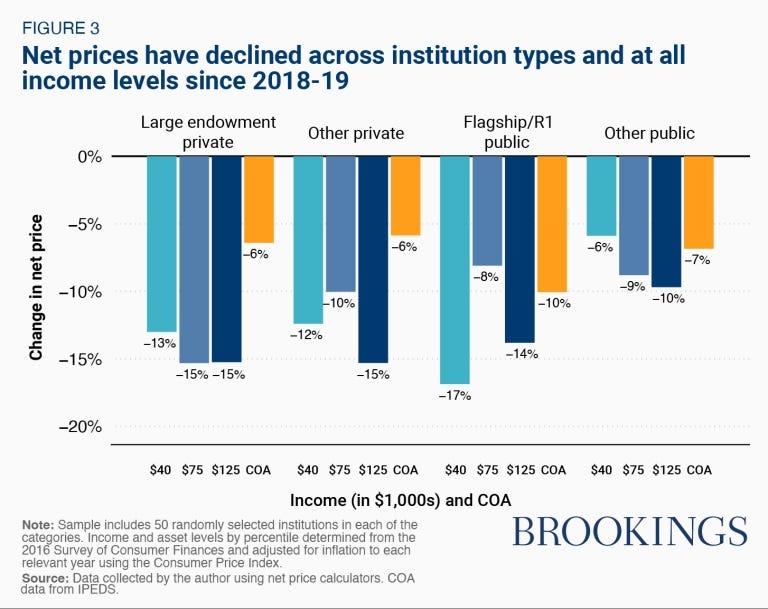

And yes, tuition is falling even when include financial aid:

The lack of demand is compounded by a slowly shrinking population of young Americans.

All together, the drop in demand for college is forcing many institutions to close down:

Since 2016, 91 U.S. private colleges have closed, merged with another school, or announced plans to close, according to a CNBC analysis of data from Higher Ed Dive. Almost half of those schools closed after the onset of the Covid pandemic in 2020. For many struggling schools the pandemic was the final straw — but two major themes showed up consistently throughout the closures: finances and enrollment.

And that in turn is threatening many of the small towns for whom a college was a tentpole and an economic lifeline.

The reason for the falling demand isn’t too hard to ferret out; it’s right there in the WSJ poll. Young people go to college to get a good job. Poll after poll establishes the fact that economic opportunities are the most important motivation for higher education.

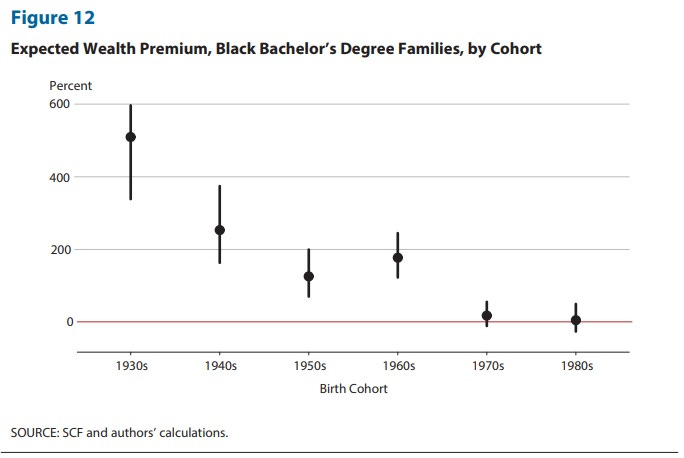

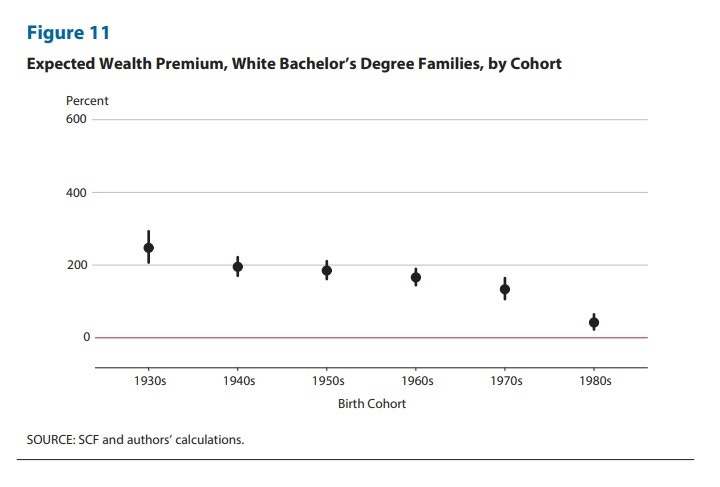

But those opportunities appear to be declining. Emmons et al. (2019) find that Baby Boomers who went to college are expected to amass around twice the wealth of their non-college peers over their lifetime. For older Millennials, the expected premium is near zero for White graduates and zero for Black graduates.

The authors find that income premiums for college graduates have also decreased, though not as much as for wealth premiums. One reason wealth premiums have declined more is certainly the rise in tuition; going into deep debt to pay for college means less wealth down the line.

In other words, for the average student, college is a less valuable investment for a much higher price than for previous generations.

This suggests that we simply sent too many students to college, and the sector is due for a natural shakeout. Economically it makes sense to keep sending more and more students to college until the return on investment for the marginal student — including all opportunity costs and risks — is zero. But the marginal student isn’t the same as the average student; for all the students who are better than the marginal student, the premium should be positive. So if the average premium is approaching zero, that means we overshot. It means we revered college a little too much as a generator of positive economic outcomes.

(Side note: College wage premiums aren’t causal estimates. Some part of the premium is due to the benefits of education, but some part is due to selection effects — i.e., to the fact that higher-skilled individuals tend to go to college, and those people would have earned above-average amounts of money even had they not gotten a degree. But this only strengthens the case that we sent too many Americans to college, since if we only included the causal piece of the premium, it would be even lower for Millennials.)

You can see increasing awareness of the falling college premium in students’ choices of majors. People who major in engineering and computer science have significantly higher expected lifetime earnings than those who major in the humanities — $3.21 million for a computer science major vs. $2.25 million for an English major as of 2019. That’s a big difference! So it’s no wonder that as the college wage premium falls, humanities majors are plunging while more practical majors like computer science, nursing, engineering, and exercise science are rising strongly. At this point, the number of CS degrees awarded is approximately equal to all the humanities degrees:

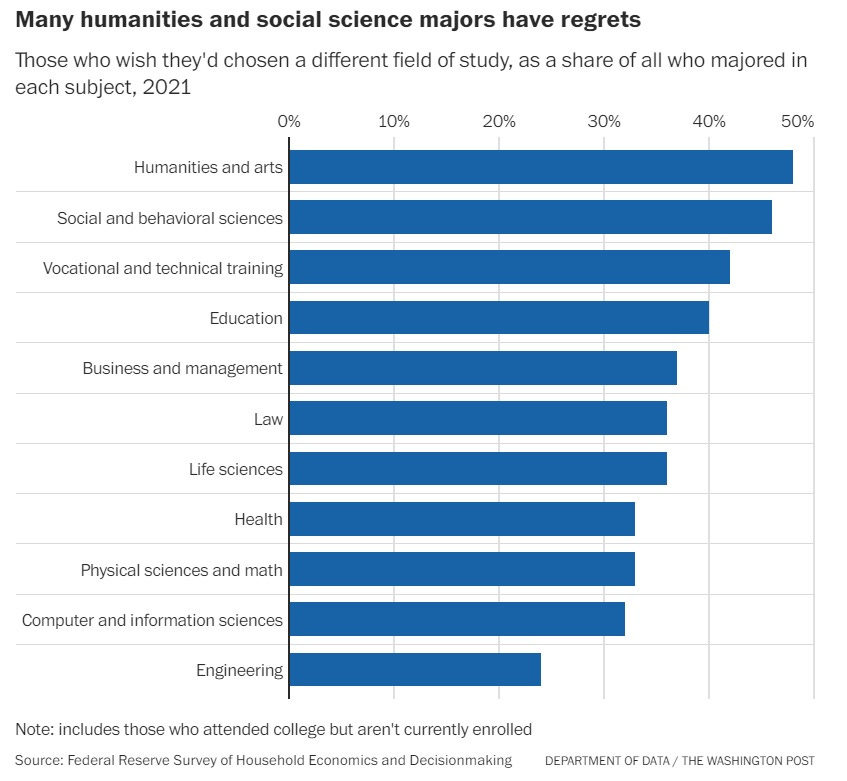

Surveys also find that those who do major in the humanities are much more likely to regret their choice of major afterward:

I see this as an indication that Americans simply came to expect too much out of the institution of college. A lot of people expected to be able to study subjects they loved and use their degree to get a great job afterwards. When it turned out to be a choice between one or the other, many regretted their decision, and wished they had prioritized the economic benefits over the self-actualization.

And if Americans are coming to expect less out of college, that’s a reason for falling demand. An institution that can deliver you a good lifetime income or personal intellectual exploration just isn’t as valuable as one that you naively believe can deliver you both of those things at once.

On top of all of this, I think there’s an increasing realization that college doesn’t always transform people into healthy, well-rounded individuals. On one hand, studies show that colleges really do teach people to be less obese and to smoke less, even after accounting for selection effects. On the other hand, rates of depression and other mental illnesses among college students have roughly doubled since 2013, and a full 44% of students report depressive symptoms. This is much, much higher than the rate among the general population.

Whether these effects persist throughout graduates’ lifetime isn’t clear; I can’t find a study on that. But what certainly is true is that college doesn’t fix people’s lives. It’s a painful, stressful, difficult time for a very large percentage of students, despite colleges’ hiring of vast armies of administrative staff to help with mental health and social acceptance.

Emotional well-roundedness is just one more benefit that Americans expected college to provide, alongside economic success and intellectual fulfillment. But it doesn’t seem to be a golden ticket for that, either.

The elite college racket

Finally, I should say something about elite schools. If Americans expected colleges in general to provide them with everything they possibly wanted out of life, they expected top schools like Harvard and Stanford to do even more — to furnish the country itself with a diverse, well-trained elite. A new paper by Raj Chetty, David Deming, and John Friedman that’s making the rounds suggests that these schools are doing worse at these tasks than we would like.

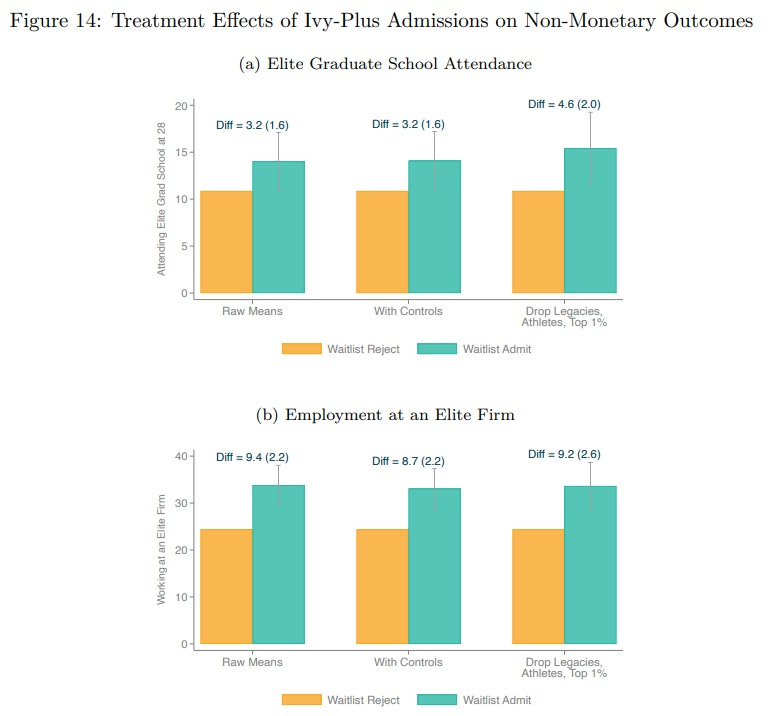

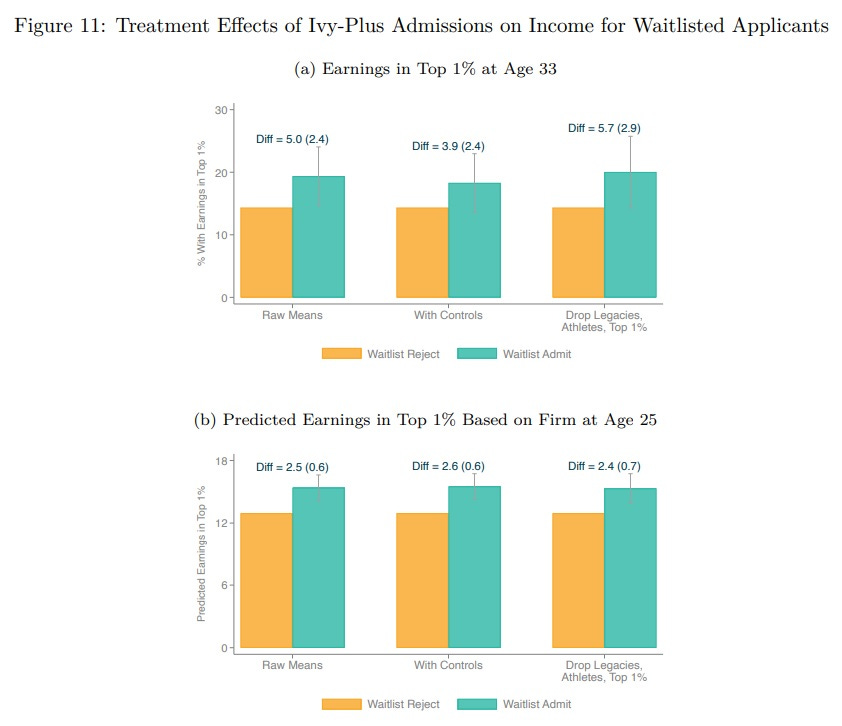

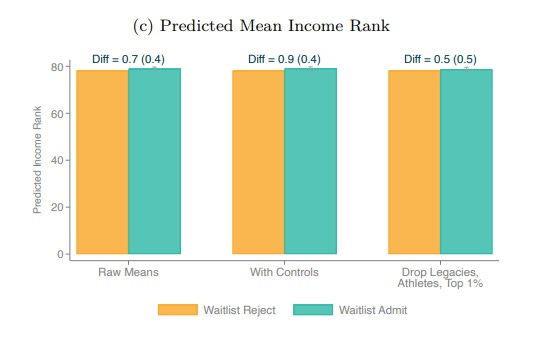

Looking at students on the waitlist that get admitted versus those who get rejected, Chetty et al. claim to isolate both the causal factors that get people admitted to elite schools, and the lifetime benefits they reap from being admitted. That top schools are feeders to the country’s elite is not in question; getting into an “Ivy plus” college significantly boosts your chances of attending a top graduate school, being employed at a prestigious company, or being in the top 1% of earners.

But like a number of other studies on this topic in recent years, Chetty et al.’s paper calls into the question the overall educational benefit of elite schools. Although students who just barely get into Harvard or similar colleges are more likely to get into the 1%, on average their earnings get no boost relative to those who just barely missed the cut.

Mathematically, these facts together must mean that for some students, getting admitted to an elite school actually damages their future income. In other words, these schools are a gamble. But more importantly, what this shows is that on average, these supposed centers of excellence are not imparting the sort of human capital that increases people’s earning power.

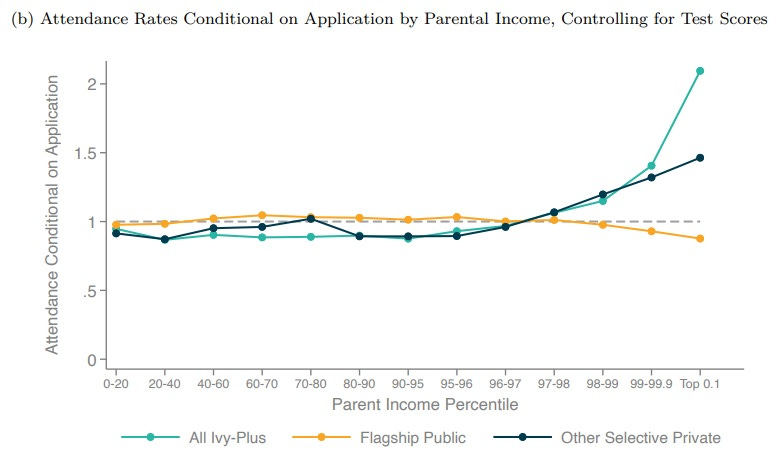

Also, as many news outlets have reported with great indignation, elite schools give extreme admissions preference to rich kids, whom they select using things like legacy admissions and athletic preferences for sports that only rich kids tend to play.

Honestly, you can’t really expect elite private schools to do otherwise. These colleges aren’t supported by the state, so they have to make more of their money via alumni donations. That means, in essence, they need to sell spots — i.e., admit a few rich kids whose parents are likely to give big gifts to the school out of gratitude, or who will themselves give those gifts when they eventually become rich themselves. And when you set the very rich kids aside, Chetty et al.’s result shows that elite schools give a bit of preference to working-class and middle-class kids over the kids in the 70th through 99.9th percentiles. That’s probably good for diversity, equity, etc.

But overall, what we have here is a picture of “Ivy plus” colleges as status merchants, selling rich people the opportunity to place their kids among the nation’s elite, while providing no overall earnings benefit to their students. That’s a pretty strong indictment of these schools as an American institution.

It also calls into question whether the chattering classes’ constant focus on equity in elite school admissions is misplaced. Yes, “Ivy plus” colleges do offer a higher chance of entering the academic and professional elite, so the composition of their student body probably does have some nonzero impact on who works at Google or gets into Harvard Law. On the other hand, Chetty finds that top public schools don’t give much preference to rich kids. And because it’s very likely that colleges overall raise incomes but elite colleges don’t, that means that non-elite schools must be doing the heavy lifting of actually building the nation’s human capital. That strongly argues for focusing a lot more resources — and prestige — on public universities in America. In particular, I recommend focusing resources on the lower-ranked public schools that provide a leg up for the children of the working class — the Cal State and SUNY and CUNY schools, etc.

In any case, elite schools seem to be another case in which Americans have simply expected the institution of college to do too much. These schools simply aren’t set up to create the kind of diverse, hyper-competent elite that many expect them to provide.

Overall, Americans are starting to realize that although higher education is an important institution, it’s not magic. We placed too many of our national hopes and dreams on its back, and we set ourselves up for disappointment. That doesn’t mean we should downsize higher education; it simply means we should downsize our expectations for the sector. Instead, we should focus on fixing our other institutions — our civil service, our health care system, our industry, and so on. A nation works best when it’s firing on all cylinders.

So I really like and respect your writings on higher ed, Noah, and I am desperate to read that poem, which gets at something I wondered about with this piece: the subject is college but not knowledge! From my position as dean the key component part I am required to deliver is a curriculum, is teaching. (You mention teaching twice but not as an activity.) In my decades in higher ed I have seen a reduction in that teaching component compared to all the other goods college is supposed to be delivering now: a sense of identity, belonging, skills for social mobility, a premiere residential experience (at some places), access to sporting events (at some places), access to Greek life (at some places), etc. So from my perspective it bears noting that my small component -- delivering a curriculum, supporting excellent teaching and the delivery/transfer of knowledge to hungry young minds -- is still what we should do and I don't blame graduates for being sad that they're getting less of that for the money.

Oh and PS -- humanities majors are in fact rising at many places, including UUtah!

I find it a little weird to see the survey response that college is not worth the cost "because people often graduate without specific job skills..."

People, you know you can pick your own major, right? So, maybe just don't make bad choices?

Like I painfully recall switching majors because I wanted to be sure my degree that would line up to a job. And I say "painfully" because in the 90s I switched from Math (too theoretical) to Business and then watched my math friends make crazy money as Wall St quants. Sigh.