American workers need lots and lots of robots

With the power of automation, our workers can win. Without it, they're in trouble.

For about five years now, I’ve been seeing people argue that vast numbers of American workers are on the verge of being automated out of a job. Bill Gates suggested a tax on robots to prevent this from occurring. Other tech figures also worried, but went with UBI as their preferred solution. It’s not just tech magnates, though — the economists Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo have been writing quite a lot of research papers warning of danger from automation. And many research reports from think tanks and corporations over the years have warned that a huge percentage of American jobs are at risk of automation.

The fear of the “rise of the robots” has filtered through to the general consciousness. Four years ago, a fellow Bloomberg writer insisted to me that truckers were about to be mass-automated out of a job. Some progressive thinkers I know who are very much into the notion of “supply-side progressivism” nevertheless recently told me that they think innovation needs to be carefully monitored by academics in order to make sure that we don’t create technologies that throw millions of people out of work or send wages crashing. On the libertarian side of the fence, opponents of the minimum wage warn that higher minimum wages will accelerate automation and put low-income workers out of a job.

That this fear cropped up during the late 2010s is no surprise. Employment levels were depressed for years following the financial crisis. The wages of middle- and working-class Americans had been stagnating — or declining outright — for decades, even as the incomes of capital owners soared. It was natural to think that technological changes might be one of the culprits, especially since innovation in machine learning/AI was racing ahead. And I also suspect that in an era of pervasive social unrest like the late 2010s, the idea that we might blame unthinking robots for our troubles instead of any group of human beings was naturally seductive.

Frankly, every time I’ve read about this “rise of the robots” fear, I’ve felt the urge to tear my hair out. Because there were always two huge, huge problems with the thesis. The first is that while it makes a great science fiction story, so far there just aren’t any signs that it’s happening. And the second problem is that if we really want to change our economy in all the ways we’ve been hoping — reshoring manufacturing from China, securing supply chains, preventing inflationary bottlenecks, and so on — we’re going to need quite a lot of automation. Indeed, if the progressive project is to be revived in America, it will need robots to carry it forward.

So let’s go through all the ways that the “rise of the robots” just hasn’t happened yet, and then talk about why we need to become a leader in automation.

Robot fears just haven’t come true yet

The central fear of automation is that it will render human workers obsolete, just as horses were once rendered obsolete by mechanization. This is possible in theory, but as of today it’s pure science fiction. In today’s America, almost everyone that wants a job has one. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio — in my assessment, the best single indicator of the labor market — is now at about the same level as at the peaks of 2019, 2007, and 1990.

Only the late 1990s did better. But we might go even higher still — the economy added 315,000 new jobs in August. It’s clear that with all the robots and A.I. and self-checkout machines and whatnot, the American economy is still capable of providing a job to practically anyone who wants one.

A more nuanced version of the “rise of the robots” thesis is that even if the labor market is flexible enough to keep everyone employed, competition with robots will push down wages, especially for “low-skilled” workers at the low end of the income distribution. But in fact, for the last decade or so, wages at the low end of the distribution (1st and 2nd quartiles) have been outpacing wages at the high end:

Real wages are now falling because of inflation, but for low-wage workers they’re falling by a lot less, or even rising for some. And real wages rose strongly in the late 2010s. So I’m just not seeing the robotic competition in the macro data.

The second reason the “rise of the robots” thesis is dubious is that if we were really automating a bunch of jobs, we’d expect to see productivity boom, as it did when agriculture was mechanized a century ago. But total factor productivity growth, while it has recovered somewhat from the doldrums of the early 2010s, is not yet back up to where it was in the late 90s and early 00s:

So we’re just not seeing mass automation in the productivity statistics either.

Finally, there’s the international evidence to consider. Industrial robots are just one part of automation, but they’re easy to measure and count, and they’re something people focus on a lot. And when it comes to industrial robots, the U.S. lags far behind South Korea, Singapore, Japan, Germany, and Sweden:

Now, two things to note. First, none of these countries seems to have a significant unemployment problem. Second, they all have higher percentages of their workforce employed in manufacturing than the U.S. does:

So the countries that use lots more robots in manufacturing than we do are actually managing to put more human beings to work in manufacturing.

And those truck drivers that my Bloomberg colleague insisted would soon be obsolete? In 2021, their wages soared, and the industry freaked out about a shortage of drivers.

So despite all the panic, the overall macro data doesn’t show any sign of mass technological unemployment or wage destruction yet. It is still in the category of “things we can write a sci-fi story about, but which have never actually happened”.

What does the research say?

What about when we look at the more subtle messages in the microeconomic data? Here, too, there’s no cause for alarm — in fact, so far, automation seems to be complementing humans more than replacing them.

The academic argument about technological unemployment really heated up when Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo came out with a paper in 2017 claiming that industrial robots kill jobs and reduce wages in manufacturing. Looking at particular industries in particular locations, they found that more robots corresponded to worse labor market outcomes in a certain industry and place. (Acemoglu especially is a huge name in the macroeconomics world, so this made a lot of waves.)

But Larry Mishel and Josh Bivens of the Economic Policy Institute came out with a convincing rebuttal of this finding. Most importantly, they noted that the result only holds for the narrow category of industrial robots; according to Acemoglu and Restrepo’s own data, overall investment in information technology, which includes all other forms of automation, was positively correlated with employment.

And in the years since Acemoglu and Restrepo came out with their frightening result, a number of studies have taken a deeper look at the data and concluded that automation is, if anything, good for human employment. I’ll list a few of these studies:

1. Mann and Püttmann (2018) — Where Acemoglu and Restrepo (2017) looked at correlation, this paper attempts to identify causation. They look at automation-related patents in an industry — a proxy for innovation in the automation space — and then look to see whether that industry gains or loses jobs. They find that “advances in national automation technology have a positive influence on employment in local labor markets”, though this isn’t true for every area.

2. Dixon, Hong and Wu (2021) — These authors looked at robot adoption in Canada, at the level of the individual company (or “firm”, as economists say). They found that companies that adopted more robots hired more people, while also improving the quality of their products and services.

3. Koch, Manuylov and Smolka (2019) — This paper looks at firm-level data for manufacturing companies in Spain. They find that robot adoption is associated with a substantial increase in employment as well as output.

4. Adachi, Kawaguchi and Saito (2020) — This paper finds the same thing as the previous one, but for Japanese companies over the course of a 40-year period.

5. Eggleston, Lee and Iizuka (2021) — These authors look at robot adoption by nursing homes in Japan, and find that it strongly increases employment, although it does result in existing nurses working fewer hours (and thus getting paid less).

6. Hirvonen, Stenhammar, and Tuhkuri (2022) — This paper looks at a technology subsidy program in Finland that increased adoption of a broad range of advanced technologies at Finnish firms. They find that this led to employment increases.

In fact, by this point the trend is clear. Essentially everyone is finding that, contra Acemoglu and Restrepo (2017), robots are correlated with — and probably cause — higher employment in the companies and areas where they’re adopted.

What’s happening is that companies that use more robots hire more humans (and retain their existing humans) in jobs that complement the robots. That’s exactly what we saw with previous waves of automation — people find new roles, robots increase their productivity, and they get paid more. Looking at the countries that use the most robots in their manufacturing industry, it seems likely that this virtuous cycle is happening even at the level of whole nations.

Zooming out from just the manufacturing sector, Hötte, Somers, and Theodorakopoulos have a very interesting 2022 review paper in which they look at the literature on the entire range of automation technologies. Here’s an article in which they explain their results. Hötte et al. find that automation does replace jobs, but that this effect is outweighed by the “reinstatement” effect — in other words, people find new jobs to do. And their incomes generally rise as a result.

And what about all those breathless reports saying that 46% or 57% or whatever percent of jobs will be automated away? They are, to put it bluntly, hogwash. I wrote a Bloomberg post about these studies back in 2018. Basically they go around and show a bunch of engineers a list of tasks, and then ask the engineers “Could you automate this?” And of course the engineers tend to say “Yeah, sure I could.” But even if the engineers are right, this sort of survey says nothing about whether the tasks associated with a job will simply change. For example, if my job is to spend all day plugging data into Excel (shudder), and then I get an AI assistant that does this for me, maybe I’ll get laid off — or maybe I’ll simply keep my job, and the assistant will free me up to do more valuable things, like cleaning the data or looking for ways to use the data. On top of this, these studies say absolutely nothing about labor markets as a whole. So really, when you see headlines like “47% of jobs will be automated away”, you should just ignore it completely.

Anyway, the question of exactly what automation does to labor markets, to individual workers, to specific industries, and to the economy as a whole is an incredibly deep and interesting one. Lots of economists are thinking about this. For example, Agrawal, Gans & Goldfarb have a lot of work thinking about whether AI will replace white-collar workers or simply make them more powerful, as machines did for factory workers. Brynjolfsson, Mitchell, and Rock have been thinking about this topic as well. Bessen has an interesting paper looking at the history of how automation led to industrial shifts.

So there’s just a lot we still don’t know. But the weight of evidence so far seems to indicate that while it’s disruptive to existing industries, companies, and workers, automation ultimately benefits workers as a whole.

Why American workers need robots

In recent years, there has been increasing talk of reshoring our industrial base from China. For a long time this was just talk, but in the past year, thanks to China’s policy missteps, reshoring finally seems to have begun:

The construction of new manufacturing facilities in the US has soared 116% over the past year, dwarfing the 10% gain on all building projects combined…There are massive chip factories going up in Phoenix…And aluminum and steel plants that are being erected all across the south[.]

In order to make reshoring happen, though, we will need automation, automation, and more automation. We are a capital-rich, high-technology country with high wages — the only way we can compete effectively with China is by leveraging our superior technology and our abundant capital. In other words, we can beat China in manufacturing, but only if we use lots and lots of robots, AI, and every other kind of automation we can think of. This is how Singapore has revived their manufacturing sector; we need to take a page from their book. Only with robots can our workers win.

On top of that, we need things like port automation in order to update the creaking supply chains that helped spark inflation in 2021.

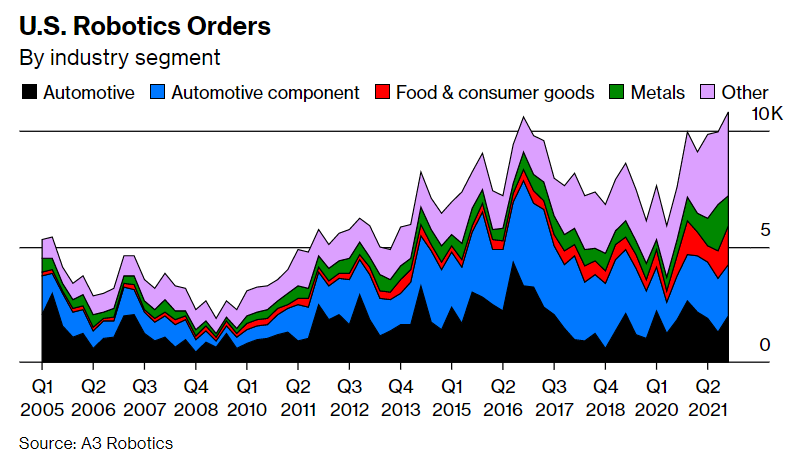

Fortunately, American companies seem to finally have seen the light. Orders for robots are rising:

And it’s not just in manufacturing industries, either. As this long and excellent Businessweek article by Thomas Black reveals, companies of all sorts are buying more robots, and in some cases leasing them as well:

This boom could be strangled if governments adopt policies to discourage automation — or if unions fight it. In Rotterdam in the Netherlands, the dockworkers’ union has embraced port automation, realizing that it will mean more work and higher wages; on the U.S. West Coast, the dockworkers’ union is resisting port automation, terrified that it will kill jobs. (Update: A commenter pointed me to an excellent article about how Sweden’s unions are embracing automation.) Meanwhile, my conversations with “supply-side progressives” suggest that they’re still stuck in 2017 when it comes to this issue — still terrified of the specter of AI and robots making millions of Americans obsolete.

This attitude needs to do a 180, and we don’t have a moment to lose. U.S. unions need to look to their European peers, and understand that technology magnifies worker power rather than replacing it. And progressives need to realize that discouraging automation in the hopes of preserving jobs is really just a form of make-work — and if our industries get out-competed by China’s because we refuse to automate, there simply won’t be as much work to make.

America’s collective panic about automation is just another manifestation of the backward-looking, hunkered-down, defensive mode we adopted in the wake of the Great Recession and the social disruptions of the 2010s. But the 2010s are over, and the great robot freakout should be left in that decade where it belongs. If we try to fight the future, it will be our own workers who lose out. Instead, for the sake of those workers, and of our country as a whole, we need to make sure that America is #1 in automation.

Excellent. Especially use of stats and graphs to build argument.

A "progressive" who can't think of anything better for humans to do than churn out widgets on an assembly line is, ipso facto, not "progressive" in any sense of the word as I would use it.