America needs a bigger, better bureaucracy

They're from the government, and they really are here to help.

This is a picture of Deirdre Beaubeirdre, a character from the comedy sci-fi movie Everything Everywhere All At Once — an IRS auditor who hounds the immigrant protagonists mercilessly. I loved that movie, but I also thought Deirdre’s character was emblematic of a common and unhelpful way that Americans tend to think about the civil service. Ronald Reagan famously said that “the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I'm from the Government, and I'm here to help.” I think that antipathy toward government workers has filtered through to much of American society — not just to libertarians or conservatives, but to many progressives as well.

I believe that the U.S. suffers from a distinct lack of state capacity. We’ve outsourced many of our core government functions to nonprofits and consultants, resulting in cost bloat and the waste of taxpayer money. We’ve farmed out environmental regulation to the courts and to private citizens, resulting in paralysis for industry and infrastructure alike. And we’ve left ourselves critically vulnerable to threats like pandemics and — most importantly — war.

It’s time for us to bring back the bureaucrats.

Aggregate numbers give a decent general impression of how the United States’ civil service has withered over the decades. This process began in the 1970s, before Reagan ever took power, and has continued to this day. The percent of American workers employed by the government rose through 1975 and fell thereafter, interrupted only by recessions (in which government employees were less likely to be laid off):

It’s worth noting that much of this decline was at the federal level. State and local governments employ a lot of people in public education and policing, which are both harder to cut:

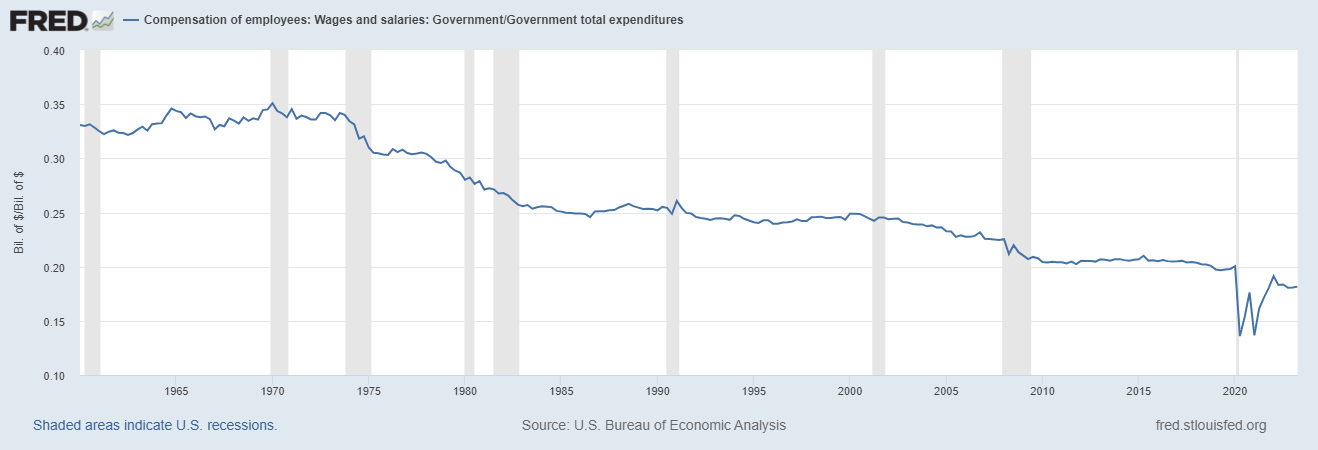

An even better way to see the decline might be to look at government spending on wages and salaries as a percent of total government spending. This represents the percent of government dollars that actually goes to pay government workers. It held steady until the mid-70s at around 34%, and then collapsed in the late 70s and early 80s to around 25%. It has since fallen to around 18% — about half of what it used to be.

If government spending isn’t going to pay government workers, it must be going to pay people who work in the private sector — nonprofits, for-profit contractors, consultants, and so on. In other words, state capacity is being outsourced. But this graph doesn’t actually capture the full scope of the decline, because it doesn’t include outsourcing via unfunded mandates — things that the government could do, but instead simply orders the private sector to do, without providing the funding.

I’m far from the first person to sound the alarm about this. John DiIulio wrote a book in 2014 called Bring Back the Bureaucrats: Why More Federal Workers Will Lead to Better (and Smaller!) Government, which is the basis for many of the ideas in this post and others. More recently, Brink Lindsey of the Niskanen Center put out a great report in 2021 called “State Capacity: What Is It, How We Lost It, And How to Get It Back”. A few excerpts from the executive summary:

A series of calamities during the 21st century—the Iraq War, Hurricane Katrina, the financial crisis, and most recently the COVID-19 pandemic—have made it painfully clear that American state capacity is not what it once was…On the right, healthy suspicion of rapid government expansion has given way to a toxic contempt for government and public service per se. On the left, efforts to expand “citizen voice” in government as a check on abusive power have produced a sclerotic “vetocracy” that makes effective governance all but impossible…

[The Niskanen Center is] taking on five new issues that we see as critical arenas for the struggle to rebuild state capacity: (1) expanding and upgrading the federal workforce, (2) improving tax collection and closing the tax gap, (3) overhauling how the federal government acquires and uses information technology, (4) streamlining environmental review to reduce delays and cost overruns in infrastructure projects, and (5) revitalizing the country’s sclerotic public health institutions to better prepare for the next pandemic.

This is in concert with Tyler Cowen’s concept of “state capacity libertarianism”, which he outlined in January 2020 as an alternative to traditional libertarianism or classical liberalism.

Meanwhile, on the progressive side of the aisle, writers like Ezra Klein have begun to focus on low state capacity as a reason why it’s hard for progressives to accomplish their objectives. Don Moynihan has also written a bunch of good stuff on the topic, including this post:

A bunch of people across the ideological spectrum are thus homing in the same conclusion: America needs a better bureaucracy. Here are just a few of the reasons why.

Bureaucrats vs. NEPA

Maybe this is just my personal experience, but I find that when Americans say the word “bureaucracy”, they tend to mean “a bunch of regulations and red tape”, rather than “the civil service”. This sets up an implicit dichotomy between private-sector individuals and companies that just want to do their thing, and civil servants who work tirelessly to enforce rules that prevent them from doing their thing.

For example, this is the depiction of environmental regulation in the movie Ghostbusters (another of my favorites). Our heroes have set up a private business trapping and imprisoning dangerous ghosts. Then Walter Peck, a bureaucrat from the Environmental Protection Agency, shows up and tells them that the rules forbid them from doing this, eventually managing to shut them down (which causes a citywide catastrophe).

This is also the depiction of environmental regulation in The Simpsons Movie, in which the EPA tries to stop pollution by sending an army to take over Springfield and encasing it in a giant dome.

But in fact, this is not actually how the most cumbersome environmental regulation works in America! Instead, we have laws like NEPA and its stronger state-level equivalents like CEQA, which farm out the job of environmental regulation to citizens and the courts. The way it works is this: A developer starts work on a project, like a solar plant or an apartment complex. Then private citizens who don’t want that project in their backyards — because of concern over scenic views, or property values, or “neighborhood character”, or whatever — sue the developer in court. Even if the project satisfies all relevant environmental laws from day 1, citizens can sue the developer under NEPA or CEQA to force it to stop the project and complete a cumbersome environmental review — basically, a ton of paperwork. This often delays the project for years, and drives up costs immensely — which of course discourages many developers from even trying to build anything in the first place.

Enforcing environmental regulation via judicialized procedural review has had devastating consequences on America’s ability to build the thing we need. Housing projects are routinely held up by NIMBYs using environmental review laws to sue developers, often under the most ridiculous of pretexts (such as labeling human noise from apartment complexes a form of pollution). The solar plants and battery factories and transmission lines that we need to decarbonize our economy aren’t getting built nearly as fast as they should, because they’re getting held up by these review laws. And remember that most of these projects aren’t violating any environmental review laws in the first place — the NIMBYs have the right to sue and hold up development regardless of whether any regulation is actually being violated!

Which raises an obvious question: How can we know if no environmental regulation is being violated, other than waiting for a lawsuit and a multi-year environmental review? The answer is: bureaucrats. The answer is that you have a bunch of government workers examine the project and make sure it checks all the relevant regulatory boxes, and then if it does, you simply allow the project to go ahead, without lawsuits or multi-year studies. This is called “ministerial approval” or “ministerial review”. This is how Japan does things, which is why they’ve been able to build enough housing to keep rent affordable.

NIMBYs are absolutely terrified of ministerial review. I strongly encourage you to read this thread by Jordan Grimes, detailing the dismay of a NIMBY pressure group at a raft of new pro-housing laws in California. The most terrifying prospect, for the opponents of new housing, turns out to be “as-of-right” development, which means a bureaucrat gets to decide whether to allow a housing project rather than a lawsuit and a judge.

In other words, environmental regulation doesn’t threaten America’s economy via a sea of red tape enforced by an army of punctilious bureaucrats. It threatens America’s economy via a plague of lawsuits and pointless paperwork that we implemented as an alternative to hiring an army of punctilious bureaucrats. If we scrapped this legalistic permitting regime and replaced it with an army of bureaucrats, we would still be able to protect the environment just fine, but we would be able to do it without causing insane multi-year delays and driving costs to the moon.

The nine most terrifying words in the English language are not “I’m from the Government and I’m here to help”. Nine far more terrifying words are: “Please spend four years completing your Environmental Impact Statement.”

Bureaucrats vs. nonprofits and consultants

Even as environmental regulation has been outsourced to the courts, a huge variety of other government functions have been outsourced to nonprofits. In a post back in May, I argued that this represented a toxic compromise between anti-government conservatives who wanted to shrink the state and progressives who wanted to increase community input into policymaking:

Some excerpts from that post:

We do know that about a third of nonprofit funding comes from government purchases and grants, and that nonprofit revenue rose by about 70% in inflation-adjusted terms from 1998 to 2016. A rough back-of-the-envelope calculation — $2.62 trillion in nonprofit revenue in 2016, 32.3% from government — says that this would equate to around $850 billion in government spending on nonprofits in the U.S.

That’s about 13% of all government spending, including state and local, spent via nonprofits. Compare that to about 18.4% of government spending spent on actual government workers as of 2022. We’ve outsourced a significant amount of our government to nonprofits. Here’s a brief overview of some of the ways this work is outsourced. Of course the number includes things like public university funding (universities are also nonprofits). But a lot of it is just paying organizations to administer government spending.

Outsourcing government functions to nonprofits — which is definitely a form of privatization, even if no one is officially making a profit — has a number of problems. First there’s the obvious danger of corruption, in which nonprofits line their pockets by using taxpayer money to help elect leaders who give them more taxpayer money. Of course this money is paid out in executive salaries rather than “profit”, but it amounts to the same thing.

But even more important is what economists call an “agency problem”. Nonprofits would rather get the government to give them as much money as possible; they would love to rip the government off. And if all the expertise involved in building housing or providing social services resides in the nonprofits instead of the government itself, the government doesn’t have the ability to judge whether it’s getting ripped off. Here’s how I put it in my earlier post:

When the government controls the purse strings but only the contractors know how much things should really cost, you get the worst of both worlds — a government that doesn’t know how to save taxpayer money, paying contractors who don’t want to save taxpayer money.

This problem is especially acute in San Francisco, which makes it extremely difficult to hire workers for the civil service, and has taken nonprofit-outsourcing to an extreme. (In fact, if you want to read a fun satire about nonprofit-outsourcing in SF in the late 60s and 70s, check out Tom Wolfe’s essay “Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers”.) Investigations have shown that oversight of SF nonprofits has been extremely poor — in part because the city got rid of the bureaucrats who could have done that monitoring effectively. Massive inefficiencies are allowed to fester for years, only coming to light after elected officials discover the problems and raise the alarm. The most recent blowup I’ve seen is over an addiction treatment nonprofit:

A San Francisco supervisor is calling for an audit of the city’s largest addiction treatment nonprofit after word leaked that a staffing shortage forced the organization’s detox program to pause intakes last week…

HealthRight 360 is the largest drug treatment provider in San Francisco and is slated to receive more than $200 million from the city this fiscal year, according to a city database.

“This is not to cast aspersions on anyone, but I am truly concerned that we are paying for a service that they’re not able to provide,” Stefani said at Tuesday’s hearing.

Of course this doesn’t mean that bureaucrats always have the right incentives. With the wrong funding incentives, civil service agencies can fall into a trap in which they try to maximize the amount they spend each year in order to increase their budgets for future years. An efficient bureaucracy requires avoiding perverse incentives like that. But when the funds are being spent via nonprofits instead of government workers, the incentives are much harder to get right, because the government lacks most of the levers of control that it has over its own workforce.

Of course, the agency problems doesn’t just apply to nonprofits, but to any government contractors. And when it comes to transportation planning, a huge problem is the amount that governments have come to rely on consultants. The Transit Cost Project has been looking into the question of why it costs so much more to build each mile of train in the U.S. than in other rich countries (most of which have stronger unions). Their big report, released earlier this year, found that state and local governments’ excessive reliance on outside consultants rather than in-house bureaucratic expertise was a huge driver of excess cost. Here are some excerpts from a great writeup by Henry Grabar:

[M]any of the [transit cost] problems can be traced to a larger philosophy: outsourcing government expertise to a retainer of consultants…

For example, when the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority got to work on the Green Line Extension, the agency only had a half-dozen full-time employees managing the largest capital project the MBTA had ever undertaken. On New York’s Second Avenue subway, the most expensive mile of subway ever built, consultant contracts were more than 20 percent of construction costs—more than double what’s standard in France or Italy. By 2011, the MTA had trimmed its in-house capital projects management group of 1,600 full-time employees (circa 1990) to just 124, tasked with steering $20 billion in investment. Perhaps the most notorious case in this business is the debacle of the California High-Speed Rail project, which in its early years had a tiny full-time staff managing hundreds of millions of dollars in consulting contracts…

It’s that lack of institutional know-how, of which consultants are both a symptom and a cause, that really hampers projects…It means staff are overwhelmed by change orders as projects evolve. In the case of New York’s Second Avenue subway, the lack of a powerful, effective team of civil servants may also explain some inexplicable conflicts and mistakes: misunderstandings and feuds with local agencies, hugely overbuilt stations, and so little standardization that the escalators in the three new stops were built by three different companies.

Would replacing some of these consultants with government bureaucrats really lower costs? A recent paper by Zachary Liscow, William Nober, and Cailin Slattery suggests that it would:

[W]e find evidence that state capacity correlates inversely with costs in a several ways. States with (perceived) higher quality DOT employees have lower costs. A state with a neutral rating has almost 30% higher costs per mile than one that rates the DOT employees as “moderately high quality”, all else equal. Consistent with the capacity hypothesis, states that flag concerns about consultant costs have higher costs. States where contractors and procurement officials expect more change orders have significantly higher costs. Frequent change orders could directly lead to higher costs through delays and costly renegotiation; they could also be a downstream symptom of poor administrative capacity at a state DOT—many contractors reference poor-quality project plans made by third-party consultants. Moreover, when we measure capacity using external data we show that states with higher DOT capacity have lower infrastructure costs. A one standard deviation increase in capacity is correlated with 16% lower costs.

And a recent paper by Maggie Shi finds that when the government monitors Medicare spending more closely, it reduces waste by a huge amount:

Every dollar Medicare spent on monitoring generated $24–29 in government savings. The majority of savings stem from the deterrence of future care, rather than reclaimed payments from prior care. I do not find evidence that the health of the marginal patient is harmed, indicating that monitoring primarily deters low-value care. Monitoring does increase provider administrative costs, but these costs are mostly incurred upfront and include investments in technology to assess the medical necessity of care.

And guess who’s responsible for monitoring Medicare spending? Bureaucrats. So that’s at least a 2300% return on investment in bureaucracy!

In sum, the years since the 1970s have been a massive experiment in whether a government, by outsourcing core functions to private actors like nonprofits and consultants, can increase the efficiency with which public funds are spent. That experiment has failed, and it needs to be reversed.

Preparing for the next threat

I became painfully aware of the problems of a weak bureaucracy during the early days of the Covid pandemic. I started a group to help encourage state public health agencies to improve contact tracing — an approach that ultimately proved futile due to hyper-infectious mutations. But back when the virus was less contagious and we still thought contact tracing might work, my partners and I had some meetings with government workers at the CDC. It was clear that they had absolutely no resources to commit to our project, and that they were overwhelmed with other demands.

Perhaps that’s to be expected in the middle of a massive pandemic. But it was also clear that the CDC workers we talked to didn’t know a lot of basic facts about how their organization worked; there was lots of data that they had no idea how to find, or even who was responsible for collecting it, and they had little concept of who was responsible for contact tracing at the state level. Those are things they should have known long before the pandemic even started.

In fact, the pathetic crisis performance of the CDC — which before the pandemic was often believed to be one of our most competent government agencies — is now the stuff of legend. Most damningly, the agency was unable to collect even the most basic data on the spread of the virus — data that private individuals were forced to collect in its stead. In addition, it made numerous bad recommendations that were later reversed, issued confusing guidance, and failed to develop Covid tests in the early days of the pandemic. The agency is now being reformed, but it’s not yet clear how deep the reforms go.

But what I’m most afraid of is not another pandemic; it’s a major war. In a widely-read post last week, I warned that a war with China over Taiwan is a lot more likely than most Americans seem to realize, and that we need to be preparing for that grim possibility right now. China’s state apparatus is famously effective in building large amounts of stuff very quickly — in the space of just a few years, while the U.S. was failing to build even a small amount of high-speed rail, China built a high-speed rail network that dwarfed American transit advocates’ wildest dreams. In a war situation, China’s massive production advantage means that the U.S. will be at a dramatic disadvantage in a protracted conflict. We do not have the equivalent of the effective bureaucracies that we created in the runup to World War 2.

But even beyond military production, the U.S. needs to do lots of preparation for the possibility of a China conflict. Private companies need to audit their supply chains to make sure they can sustain production in the event of a war. The U.S. government needs to ensure that critical minerals can be accessed without reliance on Chinese processing facilities. And the government needs to revive the defense-industrial base, so we don’t see bottlenecks of the kind we encountered when we tried to produce Covid masks, tests, and ventilators in the early days of the pandemic.

All of this requires a large, competent, well-funded bureaucracy. Yet I worry that neither progressives nor conservatives understand this need. Progressives still seem wedded to the idea of defending NEPA, while conservatives still seem wedded to the idea of slashing and burning any government agency they can. It’s a toxic equilibrium in which one side wants to drown the government in a bathtub and the other wants to outsource it to every NIMBY and nonprofit in the country.

To reestablish U.S. state capacity, we have to sail between the rocks of both of these disastrous approaches. We have to rebuild the civil service, with sufficient long-term funding guarantees, talent, and size. For all our sake, we need to bring back the bureaucrats.

Few thoughts:

1. Local bureaucracy is even more godawful than federal because local civil services are a) critically understaffed b) completely unable to find expertise and therefore are inept c) run by special interests d) run as patronage e) some combination of the above. This is one of the reasons I advocate municipal consolidation to allow for a larger pool of recruits.

2. An even scarier set of words is "there is no government and I'm here to kill you"

3. The USA is stuck in a vicious cycle of bad bureaucracy = people restrict bureaucrats and pay them less = bureaucrats do a bad job =...

4. The joke about nonprofits is "we aren't in the business of profit but we certainly aren't in the business of loss"

5. Many people who work at nonprofits are zealots/people with mental disorders that compel them to antisocial behavior (looking at you, SF Coalition on Homelessness/Fraudenbach). Building state capacity by hiring nonpartisan bureaucrats would allow cities to defund these organizations that do little but enrich themselves, pollute the discourse with their presence and commit antisocial acts. Driving their staff into unemployment might be bad for Xitter but it's good for almost everything else (also teach people that being an activist is bad mmkay).

6. The best model for bureaucracy is Singapore- bureaucrats are paid very well there to attract talent and there's a genuine sense of doing your time in the private sector and then giving back to the nation.

7. Some government agencies run on goddamn COBOL and FORTRAN. This is an utter disgrace and heads need to publicly roll.

8. The GOP's deregulatory crusade tends to be focused on removing the barriers to powerful incumbents committing abuse rather than improving economic efficiency.

9. Not quite bureaucrats but adjacent: government transit agencies like SEPTA or Metra are run by political appointees instead of bureaucrats. In the case of the MTA, politicians can force out competent leaders for disagreement.

Noah, you really need to limit comments to paid subs if you don’t want to read nutjobs here. Slow Boring does it and it’s all the better for it.