Rebutting Jason Hickel is an arduous and thankless task. A Hickel tweet can travel around the world and back again while a thorough, sober debunk of that tweet is still lacing up its boots. And yet it must be done, because the sheer virality of Hickel’s misguided narratives demands an eternal, Sisyphean pushback.

Hickel, an anthropologist by training, has two major theses about the world:

He believes that global poverty reduction is a myth, and

He believes that degrowth is the best solution to environmental problems.

Both theses are wrong. And not just wrong in the “Ackshually, sir, you don’t have the facts quite right” sense, but wrong in consequential, potentially dangerous ways. In this post I’m only going to push back against the first of these two narratives; I promise I will write more about degrowth later, and in the meantime you can read this and this.

Today’s post is about global poverty reduction. Hickel’s view, laid out in a 2019 Guardian column, is that global poverty has worsened over the last few decades:

What happens if we measure global poverty at…$7.40 per day, to be extra conservative? Well, we see that the number of people living under this line has increased dramatically since measurements began in 1981, reaching some 4.2 billion people today…

Take China out of the equation, and the numbers look even worse. Over the four decades since 1981, not only has the number of people in poverty gone up, the proportion of people in poverty has remained stagnant at about 60%. It would be difficult to overstate the suffering that these numbers represent.

This is a ringing indictment of our global economic system, which is failing the vast majority of humanity.

This couldn’t be more wrong, and we’ll get to why in a minute. But first I want to talk about why Hickel is pushing this argument.

Basically, Hickel believes that to accept the reality of global poverty reduction would mean to accept the triumph of capitalism:

These figures have been trotted out in the past year by everyone from Steven Pinker to Nick Kristof and much of the rest of the Davos set to argue that the global extension of free-market capitalism has been great for everyone.

There are certainly some people out there who push the narrative that global poverty reduction is a result of free-market capitalism. Pinker does make this claim. But Nick Kristof, in the New York Times column that Hickel links to, certainly did not make that claim. I invite you to search the column for the words “capital”, “capitalism”, “market”, or “markets”. You will not find them in the text. In fact, Kristof does not discuss the cause of global economic progress at all. He is merely celebrating the fact of global poverty reduction, as an antidote to Trumpian pessimism; he does not venture to assert a cause. Hickel has put words in Kristof’s mouth.

Why did Hickel put words in Kristof’s mouth? Because Hickel accepts Pinker’s narrative utterly; he believes that the modern global economic system (except for China, as we’ll see) is defined by free-market capitalism. And he seems to assume that everyone else, including Kristof, believes the same.

Hickel explicitly lays out his worldview in a 2019 letter to Pinker:

But what’s really at stake here for you, as your letter reveals, is the free-market narrative that you have constructed. Your argument is that neoliberal capitalism is responsible for driving the most substantial gains against poverty. This claim is not supported by evidence. Here’s why:

The vast majority of gains against poverty have happened in one region: East Asia. As it happens, the economic success of China and the East Asian tigers – as scholars like Ha-Joon Chang and Robert Wade have pointed out – is due not to the neoliberal markets that you espouse but rather state-led industrial policy, protectionism and regulation (the same measures that Western nations used to such great effect during their own period of industrial consolidation). They liberalized, to be sure – but they did so partially, gradually, and on their own terms.

Not so for the rest of the global South. Indeed, these policy options were systematically denied to them, and destroyed where they already existed. From 1980 to 2000, the IMF and World Bank imposed structural adjustment programs that did exactly the opposite: slashing tariffs, subsidies, social spending and capital controls while reversing land reforms and privatizing public assets – all in the face of massive popular resistance.

Thus Hickel believes that any success of the modern global economic system (outside China) must constitute a victory for free-market capitalism. And so to him, criticizing capitalism requires that we deny that global poverty has fallen.

But Hickel is wrong about poverty, and he is wrong about the global economic system too.

Hickel is wrong about poverty reduction

First of all, if you want to assess the change in global poverty in an ideologically neutral way, why on Earth would you exclude China? China is a fifth of the entire human race. Its reduction of poverty is one of the great success stories of humankind, and this is a thing to be celebrated, not excluded from the statistics on ideological grounds.

Second of all, even excluding China, poverty has fallen substantially in recent decades. Here, via the World Bank (which does detailed studies of consumption levels in each country), is the picture of poverty defined at the lowest level of $1.90 per day:

As you can see, at this very low level, poverty has fallen everywhere (though it has increased in the Middle East in the last few years, due to wars.)

Now let’s look at a higher level: $5.50 a day.

At this higher threshold, we see that poverty has fallen everywhere, with particularly impressive gains in Latin America and the Caribbean and Europe and Central Asia. (South Asia looks like it was accelerating in the early 2000s, but the data ends early.)

So how does Hickel deny this change? Simple: He insists that both the $1.90 level and the $5.50 level are too low to think about. From his Guardian column:

Earning $2 per day doesn’t mean that you’re somehow suddenly free of extreme poverty. Not by a long shot.

Scholars have been calling for a more reasonable poverty line for many years. Most agree that people need a minimum of about $7.40 per day to achieve basic nutrition and normal human life expectancy, plus a half-decent chance of seeing their kids survive their fifth birthday.

In his response to Pinker and elsewhere, Hickel also insists on a $7.40 threshold. In his Guardian column and on Twitter, he has hinted that this might be too low for him, and that perhaps we should insist on a $10 or higher threshold.

In other words, Hickel insists on thinking of poverty in terms of a single threshold. Instead of the real growth of living standards for poor people, Hickel thinks of poverty reduction in terms of the number of people who cross a single finish line. And he’s the one who gets to decide where that finish line lies.

In a Bloomberg post in 2019, I explained why this is not a good way to think about global poverty:

[Hickel’s] argument is both economically and morally flawed. Although higher poverty thresholds are important to look at, the lower thresholds are actually more important. A person living on less than $1.90 a day is in danger of starving to death, has no access to life-saving medical care, proper sanitation or basic education. Let's imagine her income rose to $7.39 a day. That increase would be utterly life-changing — still poor, but out of immediate danger and the grueling daily struggle just to stay alive.

But by Hickel’s accounting, this gain in income would represent no reduction in poverty, since $7.39 a day is still less than his chosen threshold of $7.40. This is reflects an analytical failure because he doesn’t appreciate one of the basic tenets of economics — the diminishing marginal utility of consumption, meaning that the less money you have, the more each small increase matters.

Hickel waved away this argument in a rebuttal, saying “Once again, I have not argued that we shouldn’t pay attention to low-level increases in income.” Except in all his later writings, he has relentlessly refused to pay attention to those increases. Instead, he has continued to treat poverty reduction entirely as a matter of crossing a single finish line. And he continues to set that line high enough to allow him to claim that poverty hasn’t fallen — moving the goalposts, when there should be no goalposts in the first place.

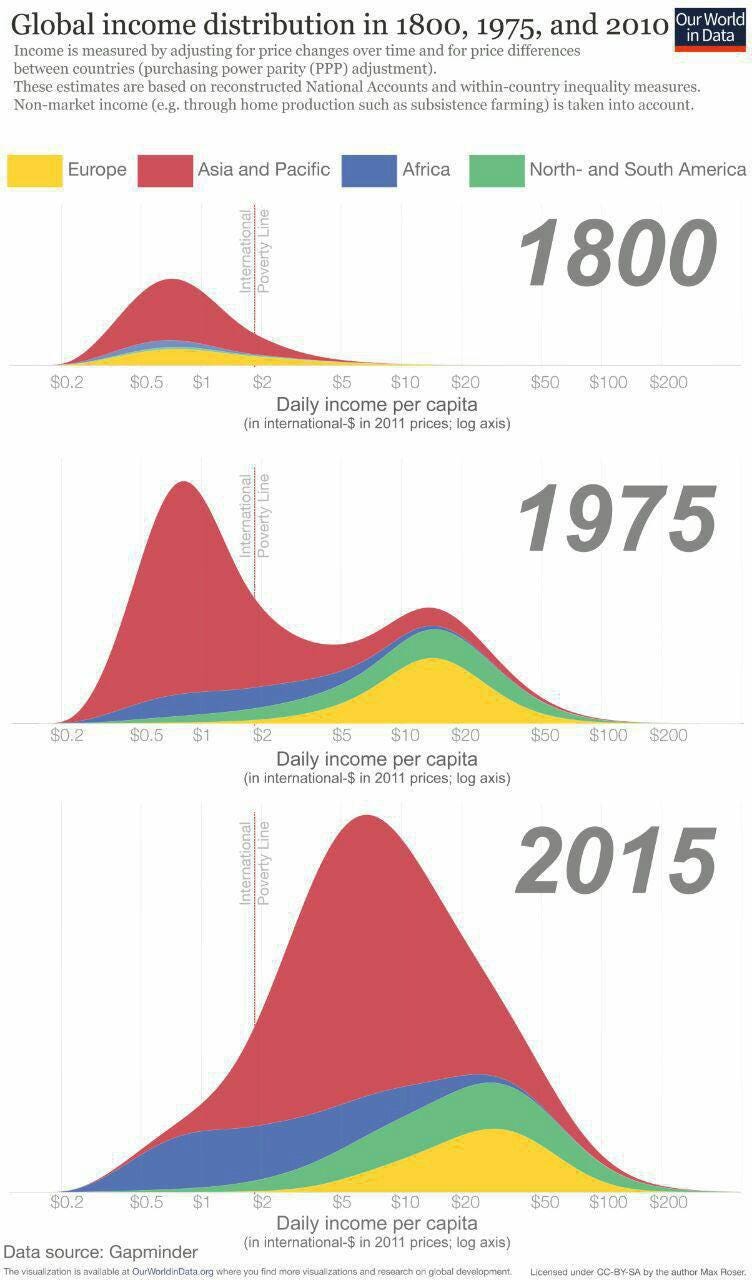

But perhaps it’s not Hickel’s fault? After all, the World Bank and other data sources define poverty at various thresholds, which might suggest that there’s one “correct” threshold. Instead, what we should really do is to look at how the distribution of global income has evolved. Fortunately, the folks at Our World in Data have produced such a picture:

Ignore the “international poverty line” on this graph — remember, we’re looking at distributions, not thresholds — and just look at the shape here. And ignore 1800, since we’re talking about recent decades. From 1975 to 2015 you see a huge rightward movement in the income distribution, with by far the biggest change happening in Asia, but with Latin America also making substantial gains. Africa is the only region that doesn’t appear to make much progress, expanding in size while its position shifts only a little.

You also see the distribution radically change shape, from two bell curves into a single bell curve. To me, that suggests that we’re looking at a picture of decolonization. But more on that in a bit.

Anyway, Max Roser has a cool animated graphic of how this distribution changed between 1988 and 2011, with a slightly more detailed breakdown:

You can see that though China is the top performer here, India and “Other Asia” have done quite well. I keep telling everyone who will listen that we’re all sleeping on Southeast Asia + Bangladesh. Anyway, you can also see that Latin America and Central Asia both do quite well.

A glance at this graph should be enough to disprove Hickel’s narrative that global poverty has increased (or even that it has failed to fall). The rightward shift of the income distribution is smooth and broad and more or less continuous. Africa’s relative lack of progress and the Middle East’s recent war-driven reversal are big worries, to be sure. But when we eschew Hickel’s threshold-driven approach in favor of a broader picture of living standards, we see that poverty reduction is widespread, and it is widespread outside China.

Hickel is wrong about the global economic system

Hickel is right (and Pinker is very wrong) about one big thing — Dogmatic free-market capitalism, of the Chicago Boys/Washington Consensus/1990s IMF variety, is not a good strategy for economic growth or poverty reduction. In his response to my Bloomberg post, Hickel bizarrely claims that I support “Washington Consensus neoliberalism” over “state-led development strategies”, but this only shows the strength of Hickel’s mistaken belief that anyone who disagrees with him must be a priest of the free market. In fact, if he had bothered to read anything that I wrote that didn’t contain his name, Hickel would know that I have been a consistent, relentless supporter of industrial policy and the development state. My friend once joked that I was a neural net trained on the book How Asia Works, since I recommend it so often.

What Hickel gets wrong is his idea that Western powers, libertarian ideology, and international institutions have conspired to keep poor countries from adopting mixed approaches to their economies. In fact, activist state policies are quite common, and have contributed substantially to the poverty reduction documented above.

For example, take India. Dani Rodrik and Arvind Subramanian, in a 2004 paper about India’s growth surge, write the following:

Most conventional accounts of India’s recent economic performance associate the pick-up in economic growth with the liberalization of 1991. This paper demonstrates that the transition to high growth occurred around 1980, a full decade before economic liberalization. We investigate a number of hypotheses about the causes of this growth—favorable external environment, fiscal stimulus, trade liberalization, internal liberalization, the green revolution, public investment—and find them wanting. We argue that growth was triggered by an attitudinal shift on the part of the national government towards a pro-business (as opposed to pro-liberalization) approach. We provide some evidence that is consistent with this argument. We also find that registered manufacturing built up in previous decades played an important role in influencing the pattern of growth across the Indian states.

In other words, India didn’t just liberalize things; it implemented its own version of a development state, and prospered as a result. The same is true of Southeast Asia, where Malaysia, Thailand, and to a lesser degree Indonesia have emerged as success stories and have relied thoroughly on development states and industrial policy. See Vietnam’s recent growth for another example.

In Latin America, it’s true that the Washington Consensus slowed down structural change and productivity growth. But that doesn’t mean Latin American governments had no role in reducing poverty. Bad advice may have held back the development state in Latin America, but governments there have engaged in extensive redistribution and better education.

A series of papers by Nora Lustig, Luis F. Lopez-Calva, and Eduardo Ortiz-Juarez documents these policies. Inequality in Latin American countries fell substantially during the 2000s:

Lustig et al. find that roughly half of this was due to government transfers and pension policies, while the other half was due to increasing incomes for workers at the bottom of the distribution — which in turn was due to better education. So Latin American governments, though they didn’t pursue the kind of manufacturing-intensive, export-led development policy used by many Asian countries, did manage to cut poverty with government action.

In fact, if there’s one country where we might make a case that liberalization and free-market capitalism did make the biggest contribution to poverty reduction, it would be — ironically — China. Privatizing state-owned enterprises and allowing in vast amounts of foreign investment have been key to China’s growth strategy. Allowing private businesses and private land ownership, albeit sometimes under the official euphemistic names of “township and village enterprises” and “70-year leases” on land, has also been important elements of China’s development.

Obviously China is no neoliberal paradise. But the capitalistic shift can easily be seen in the inequality statistics. In 2019, Thomas Piketty, Li Yang, and Gabriel Zucman documented how private property ownership and private capital accumulation have driven Chinese inequality to levels similar to that of the U.S. When Piketty included these findings in his new book, Capital and Ideology, China’s government promptly banned the book.

So China’s massive growth leap, which Hickel holds up as a successful example of non-capitalist poverty reduction, actually coincided with a radical shift in the direction of free markets, private property, private business, and inequality.

But again, this is not to say that liberalizing one’s economy is a good strategy for reducing poverty. China continued to benefit from its development state; it didn’t have much centrally planned industrial policy until around 2010, but local governments had very strong industrial policies, while the central government worked on promoting exports and making financial and real resources available to businesses. And had China adopted the redistributionary policies of Latin America, it might not be facing such a big inequality problem right now.

The real point here is that Hickel is completely wrong to hold China up as a socialist success standing alone in a world of neoliberal failures. In fact, all the countries that have been successful at reducing poverty have adopted a mixed approach — neither free-market dogma nor command economies, but hybrid affairs with large components of both activist government and private business.

Developing countries can save themselves

So Hickel’s entire paradigm for thinking about global poverty reduction is off the mark. Poverty has indeed been falling in most of the developing world, and not because of free-market capitalism.

As for the gap between rich and poor countries, it still looms large. But in percentage terms, after growing in the 60s and 70s, that gap has finally begun to shrink. Research shows that growth in the Global South has accelerated since the early 1990s, while the movement from global divergence to global convergence actually stretches all the way back to the decolonization of the 1960s.

And this is really what gets me about Hickelism. It seems to envision a world that is zero-sum, or close to it, with rich countries hoovering up the riches that should be flowing to the Global South. At the same time, it envisions the countries of the Global South as being held down and held back by the Western ideology of capitalism.

This worldview simply gives the countries of the Global South far too little credit. Rather than being drained dry, they are advancing, growing their share of the global pie even as they deliver better lives to their own poorest citizens. And they’re doing it not by imbibing neoliberal nostrums from the West, but by experimenting pragmatically with a variety of different government-based and market-based policies — in Deng Xiaoping’s famous words, “crossing the river by feeling the stones”.

That is something Nick Kristof and Bill Gates and Max Roser and Dina Pomeranz and all the other development cheerleaders are absolutely right to celebrate. While by denying these realities, or using rhetorical sleight-of-hand to obscure them, Jason Hickel is doing the Global South a disservice. By insisting that these countries are being kept down by Western neoliberal ideology, he seems to think that it’s Western intellectuals who oppose that ideology — perhaps leftish British writers? — who will be the developing world’s salvation.

I just don’t think this is how it’s going to go down. Some developing countries were hurt by the Washington Consensus and the misguided demands of the IMF, but even those that were hurt by this have managed to make a lot of progress and stage a recovery. The people in charge of these countries are smarter and less beholden to the West than Hickel gives them credit for — they know how to experiment and find what works, and they take foreign advice with several grains of salt.

So let’s not minimize these countries’ real achievements. And let’s not pretend that they need us to somehow grant them the freedom to develop. They can do this. They are doing it.

This is great! I've been trying to find a comprehensive debunk of Hickel for a while. If this is meant to be a two-parter, I'm pumped for the degrowth debunk!

Thanks for taking the time to rebut Hickel's argument! (Going to have to read "How Asia Works.")

Odd Arne Westad observes in "Restless Empire" that when China made the transition to capitalism in the 1990s, it adopted the American dog-eat-dog model rather than the social-democratic model of Western Europe.