Personally, I thought “defund the police” sounded like a good slogan. It seemed to offer something to everyone. For the anarchists, it could be interpreted as analogous to their preferred slogan of “abolish the police” — i.e., “defund the police 100%, such that they disappear”. For normies who realize that police won’t and shouldn’t disappear from society, “defund” could simply imply budget cuts — police funding diverted to social services, nonviolent alternatives, etc. And “defunding” sounded more muscular and proactive than the wishy-washy “reform”.

But instead of having something for everyone as I expected, the slogan appears to have become a point of contention. Barack Obama argued that the “defund” slogan alienates large swathes of society, prompting strong pushback from Ilhan Omar and many people on Twitter.

So…I’m not a very good sloganeer. That’s unsurprising, I guess. But the more important question in my mind is what should actually be done regarding policing in America. And it seems to me that what needs to be done is to reorient the police away from punitive actions and integrate them more peacefully into the community. That doesn’t make a good slogan, but I think it would make good policy.

U.S. cops are out of control

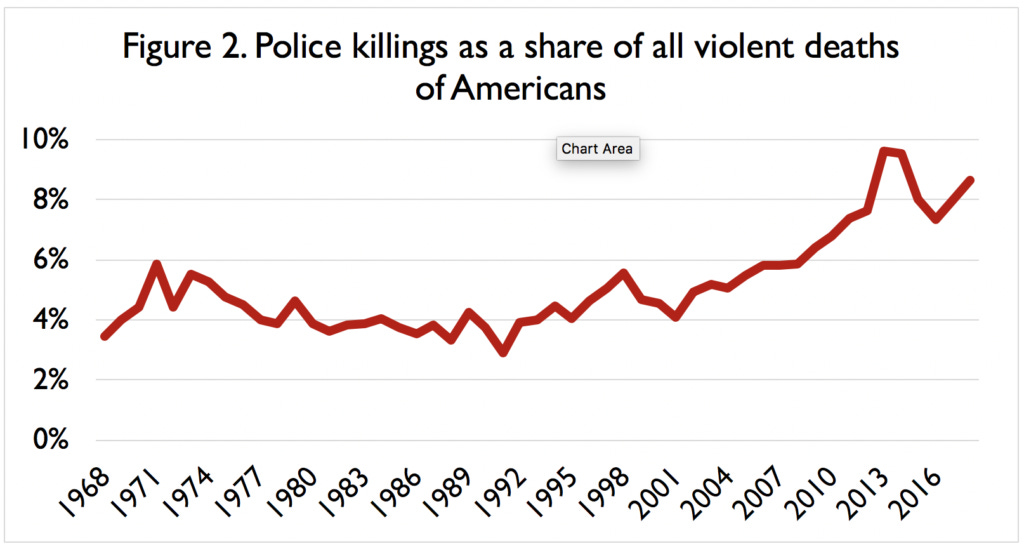

Lyman Stone (the itinerant blogger, former government economist, and Lutheran missionary) had a great post back in June detailing just how out-of-control U.S. cops are. Violent crime in America plunged in the 90s and continued to drift downward, but in the 2000s police killings soared (from about 1000/year 20 years ago to about 1800/year now). As a result, police killings went from about 4% of violent U.S. deaths at the turn of the century to about 9% in the 2010s:

This happened despite the fact that American citizens were shooting far fewer police officers than they used to. American cops have cultivated a “warrior mentality” that teaches them that they’re always under siege, about to be ambushed and killed, and that they need to deter this by responding with savage, sudden, overwhelming force.

That savage force, of course, is deployed more harshly against Black Americans. Stone calculates that Black people are greatly overrepresented among police victims in America, even after taking violent offense rates into account:

Stone concludes that cops have been on a two-decade “riot against the republic”. Watching the hundreds of videos of police brutality from around the country during the George Floyd protests this summer, it’s hard to disagree.

We’ll always have cops of some sort

But while the two-decade police riot in America needs to be put down somehow, abolishing the police is not the way to go about it. The reason is that police serve essential functions in society — deterring crime and preserving public order. If we abolished the police, someone else would start performing those functions. And it would probably not be someone we liked.

As an illustration of this, consider the CHAZ (Capital Hill Autonomous Zone), a several-block area of downtown Seattle that was seized by protesters after police were driven out of the local precinct. By day, CHAZ (later renamed CHOP) was basically a big block party, but by night it was patrolled by various armed security forces. These included various CHAZ residents, but also the John Brown Gun Club, a local left-wing militia. A zone without cops now had…cops. And just like any cops, they responded to reports of violent crime, prepared to use deadly force.

The result was as predictable as it was tragic. On June 22, CHAZ/CHOP security shot up an SUV that they apparently thought had come to attack the autonomous zone:

Unfortunately the SUV was turned out to actually be just two Black teenagers out for a drive. One teen was killed and the other put in intensive care. CHAZ/CHOP was dismantled shortly afterwards, and the Seattle police returned to the area.

This tragedy illustrates that if you get rid of the cops, you’ll get new cops, and often worse ones than the ones you got rid of. Even George Orwell discovered this during the Spanish Civil War. In his memoir Homage to Catalonia, he notes how workers hated the Civil Guards (national police). Just as police in America tend to be brutal to Black people, these Civil Guards tended to be brutal to working-class people, demonstrating what seems to be a universal tendency of police to punch down on marginalized groups. But during the Civil War, when the Anarchists in Catalonia abolished the police, the Communists came in and fairly quickly created a new police force with a slightly different name from the old one (which ended up violently suppressing the Anarchists). This was presumably because the Communists — whom today we would call “tankies” — were totalitarian control freaks. But the people of Barcelona presumably accepted the new cops because of a desire for public order and deterrence of violent crime.

More generally, every complex society on the planet has some form of cops. Japan has cops. India has cops. Ghana has cops. Venezuela has the Policía Nacional Bolivariana (PNB).

When the PNB was set up, their wages were three times as high as police wages had been before; it was thought that this would help make the police more professional and less brutal.

The U.S. doesn’t have nearly as many cops per person as many European countries, in fact — 238 per 100,000 people in 2018, compared to 429 in France, 388 in Germany, and 295 in the Netherlands (though we do have more than Sweden, Denmark, or Canada!).

The problem is how American cops behave. Despite the fact that we have fewer police per capita than Germany, and a murder rate only about 5 times as high, our cops shoot civilians at a rate 25 times as high as cops in Germany.

Actual police defunding that works

Cities and states all across the country are enacting police reforms. Many of these are deeper and more substantial than the reforms suggested after BLM protests in 2014-15. They involve things like civilian oversight boards, restrictions on the use of force, stricter hiring and disciplinary procedures, and, yes, some diversion of police budgets to other, more peaceful uses.

To me, though, the most interesting reforms involve changing what functions the police are expected to perform in society. Many of the reforms involve taking cops out of schools. In Berkeley, cops will no longer handle traffic enforcement (an idea partly credited to the excellent activist Darrell Owens). San Francisco is taking police off of 911 calls involving mental health and drug addiction, and replacing them with unarmed responders.

To me, this seems like exactly the right thing to do. Time will tell, of course. But there seems to be no reason why armed police should be the people to issue traffic tickets or help calm down a mentally ill person. And cops in schools are just dystopian. By removing these functions from police departments, we reduce the chance for violent escalation, and thus remove opportunities for police violence. And hopefully police departments, chastened by this reduction in their duties, will work harder to crack down on brutality.

This is real police defunding, since the money that would pay police to perform these functions will now go to pay unarmed responders. It’s not police abolition (sorry anarchist friends!), but it is a partial de-policing of our society. Hopefully these programs will succeed and be emulated throughout the country. Joe Biden already thinks they’re a good idea.

So what should police do?

Police still need to arrest crime suspects. This is part of the essential deterrent function of cops, because people need to know that crime will be punished; there is plenty of evidence that the existence of police officers does deter crime.

But there’s probably another way for police to deter crime more peacefully, while also integrating themselves into the communities they serve — police boxes and foot patrols.

In America, the police mostly drive around, looking for people to pull over and waiting to respond to 911 calls. In Japan, however, lots of police walk around on the street, or stay in police boxes known as koban (交番). And this totally changes the dynamic of police-community interaction!! In Japan, you can (and people often do) ask cops for directions! You can stand around and chat with cops if you like! You can even ask cops for recommendations for local shops and restaurants. And the cops themselves have a totally different experience — instead of only interacting with civilians when something bad is going on, they see thousands upon thousands of people peaceably going about their business, and interact with many of these people.

In the U.S., a cop showing up means that a dangerous, potentially violent confrontation is imminent. In Japan, it’s no big deal — just a person in a uniform standing there, like a security guard in a store.

Hopefully Americans can copy this innovation. In fact, I notice that L.A. now has one koban, near a mall!

In addition to creating routine, positive police-community interactions, police can deter crime just by walking around. Experiments with police foot patrols have found that they reduce crime substantially. In Camden, New Jersey, famed for firing and restructuring its police department in a way that cut both crime and brutality, a robust and peaceful foot patrol presence was part of the formula that worked.

Of course, kobans and foot patrols aren’t going to eliminate police brutality. Nothing will eliminate it; as long as there is a need for a government monopoly on the use of force, the people charged with maintaining that monopoly will have an incentive to abuse their powers (the “who will guard the guardians” problem). Every country has some incidents of police brutality.

But if cops become a more regular part of the community, it will hopefully cause them to shed their “warrior mentality”, and bring U.S. policing more in line with the less violent policing done in other countries. That’s in addition to things like civilian oversight boards, strict hiring and punishment procedures, ending qualified immunity, making it much easier to fire bad officers, removal of military equipment, more and better training, and stricter rules around the use of force.

Some will object to foot patrols and kobans, of course. The events of the past few years have convinced some Americans that police are an inherently violent and racist institution, and that the way to make policing better is to get it out of the community as much as possible, rather than integrate it more closely with the community.

But this is still very much a minority view. Even in June, while the George Floyd protests were still going strong, only 25% of Americans (and only 42% of Black Americans) favored cutting police budgets by even a little bit.

So police are here to stay. And because police are here to stay, it’s crucial to use a whole lot of different levers to make sure they protect and serve the community instead of beating it down. Defunding — by shifting police functions to unarmed responders — is one important lever. Changing police work from crisis response to foot patrol and community integration is another. Real change is possible.

This is entirely based on an anecdotal observation based on an extremely small sample size, so please accept that big caveat, but policing, like most occupations, seems to self-select from certain personality types: Most people I know who moved on to the police force often had an "us vs. the bad guys" disposition long before joining the force. Again recognizing this observation is based on my limited exposure, I do wonder what police departments can do to reframe recruiting to attract more "lets serve our communities" disposition and less "I want to stop the villains" or "we need to fight the enemy" dispositions, as a beginning step toward reform.

To touch on your sloganeering points, I think some of the pushback from the likes of Obama and Clyburn is that "defund the police" does not mean "reform the police". The word "defund" communicates a sense of absolute withdrawal of funds. It is much closer to abolish than reform. If I were to say my project got defunded, a majority of people would interpret that to mean the project is ended. Say what you mean instead of having to pretend it means something else. You give people an easy way to disengage with your serious arguments with poor sloganeering.