A Time of Troubles

The U.S. has fundamental strengths, but politics puts us at a difficult juncture

I’m known for writing optimistic takes on America’s future. Last year on the 4th of July I praised the U.S. for making it through an unprecedented string of difficulties over the last two decades. This March I argued that U.S. state capacity is a lot higher than people think it is. And in May I cautioned against the histrionic rhetoric of national collapse that has become popular on Twitter.

There is no reason for me to change my mind about any of these things. The U.S. retains a remarkable array of fundamental strengths — a large and well-educated populace, a huge amount of land and natural resources, favorable geographic location, a civic culture that is far more robust than people give it credit for, a multiracial and multicultural population that is very cohesive at the local level, a welfare state that’s far more robust than people realize, top scientific and technical institutions, world-class industries, and so on.

But despite these strengths, the U.S. is in trouble, because of politics. It would be foolish not to acknowledge this. The recent string of Supreme Court decisions that is upending the political-economic status quo is not (yet) a major cause of the dysfunction, but it is a bellwether of instability, and it has served as a wake-up call for many of those who thought the political conflicts of the last 8 years were just social media hype.

What is the danger, really?

The fundamental danger to the U.S. right now is internecine conflict. Our external enemies and rivals are formidable, but in recent months they have shown themselves to be less competent than we believed — Russia military, and China economically. The U.S. has managed to stymie Russia’s entire army without a shot fired, simply by supplying a bit of arms and intelligence to Ukraine. And China’s period of rapid catch-up growth appears to be over, thanks to a real estate crash, ill-advised Covid lockdowns, and a rapidly aging population. Abraham Lincoln’s famous words from his Lyceum Address still ring true:

All the armies of Europe, Asia, and Africa combined, with all the treasure of the earth (our own excepted) in their military chest, with a Bonaparte for a commander, could not by force take a drink from the Ohio or make a track on the Blue Ridge in a trial of a thousand years. At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer. If it ever reach us it must spring up amongst us; it cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen we must live through all time or die by suicide.

How will internal divisions hurt the country? One threat — though perhaps not the most dire — is that increasingly extreme political polarization will lead Republicans and/or Democrats to pursue extreme policies just to “own” the other side or to signal solidarity with their own activist bases.

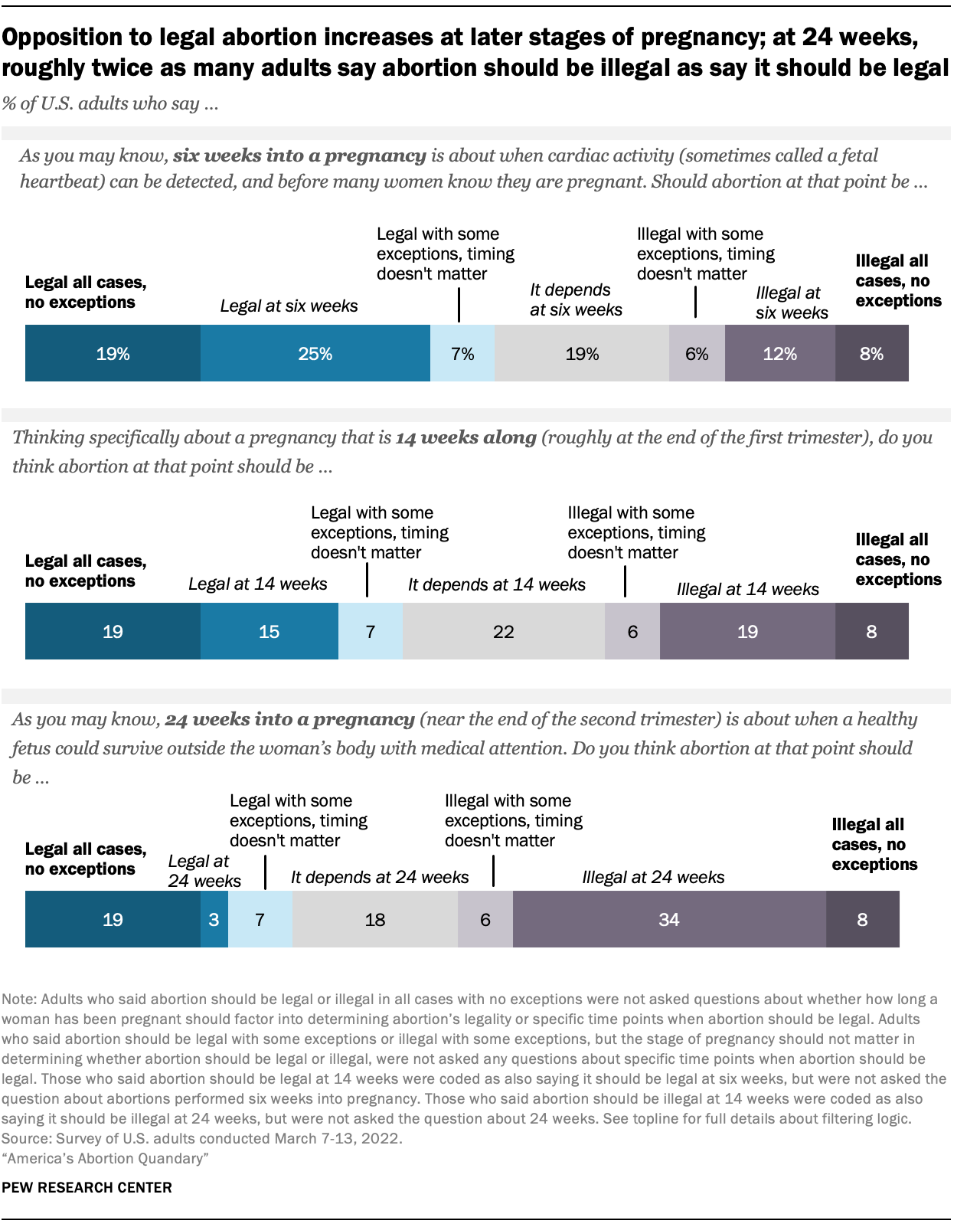

You can see this starting to happen in the fight over abortion in the wake of the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade. Some red states are implementing very extreme abortion bans, with restrictions that go far beyond anything that public opinion supports. In response, Democrats responded by putting forward a (doomed) national bill to allow abortion on demand right up until the moment of birth — a position that also goes well beyond what public opinion wants. American opinion on abortion is actually very nuanced and moderate:

This moderate position is similar to the laws that European countries actually have in place. But right now, neither of America’s political parties — or the “sides” that support them — are offering anything like this. Instead, what we face is the prospect of strongly bifurcated policies at the state level, perhaps with dramatic flips when legislatures change hands.

Of course, the threat to actual freedom is not symmetric here. Extreme abortion bans are absolutely dystopian:

How can the U.S. claim to be a defender of international freedom when some regions of our country have laws like this?

But as serious as the danger from oppressive laws may be, a far bigger danger is the erosion of democracy. 2020 already featured a sitting President denying the result of a free and fair election and attempting to abet a (doomed, incompetent) coup attempt against Congress. (In the interest of fairness, I should mention that Democrats contributed to the trend toward election-denial when Stacey Abrams refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of the 2018 Georgia gubernatorial election.) Now, hoping to double down on Trump’s approach, some Republicans are trying to change state laws so that state legislatures, rather than a state’s voters, choose which candidate the state supports in a presidential election. The Supreme Court may soon give its blessing to this sort of abrogation of voters’ will.

Whether a country is a democracy or an autocracy, or a free or unfree country, is not a binary, yes-or-no thing. Organizations such as Freedom House that track countries’ level of freedom recognize this. But it’s clear that taking away tens of millions of Americans’ right to cast their vote for President would shift the U.S. from the category of full democracies into a middle tier of flawed partial democracies.

Some on the political Right are preparing to endorse this anti-democratic shift, using the line “we’re a republic, not a democracy”. But this offers zero reassurance — North Korea and Iran call themselves “republics”. If the U.S. loses its democracy, it will matter not a bit whether we are a “republic” or not; we will be an authoritarian country. Taking away people’s ability to vote for President would be a huge step in that direction.

If the U.S. were no longer generally recognized as a democracy, it would put the lie to the country’s international claim to be the defender of democratic values. This would presumably not trouble Trump’s supporters, who are loudly stating their intention to withdraw from NATO and support Vladimir Putin’s wars of conquest.

But even more worryingly, the degradation of the U.S. into the non-democratic sort of republic would invite endemic violence and chaos here at home. People do not like having their vote taken away, as a general rule. Already there has been somewhat of a rise in political violence in the U.S., with scattered right-wing terrorism, some rioting in the summer of 2020, and Right-Left street battles that uncomfortably recall the Weimar Republic. So far, assassinations haven’t figured prominently as in the 1960s and 70s, but there was recently one plot to assassinate a Supreme Court justice. If the vote is taken away, it’s not unrealistic to think that the U.S. would suffer an equivalent of Ireland’s Troubles, Italy’s Years of Lead, or worse.

The worst-case scenario, of course, would be a full-scale civil war. The most likely trigger for this would be a disputed Presidential election, in which opposing factions of the U.S. Military backed two rival claimants to the presidency. So far, the military has resolutely avoided even the slightest appearance of dissension in the ranks, but in the case of a disputed election in which both sides had a somewhat plausible legal claim to victory, this might change. This might seem like a tail risk, but a plurality of Americans did tell a Zogby poll in 2021 that they thought a civil war is likely. And essentially ever major media outlet has envisioned a scenario of the type I just described. So this is far from idle or irresponsible speculation.

One thing I don’t think is really possible, however, is a “national divorce”, in which red and blue states go their separate ways.

Why there won’t be a “national divorce”

Suggestions for a breakup of the union have come mostly from the political Right, but some progressives have started tiptoeing up to the idea as well. But it’s extremely unlikely to happen. First of all, the U.S. political divide isn’t really regional, as it was in the 1860s when we had our first civil war. It’s blue cities against a red countryside. Here’s the New York Times’ precinct-level election map from 2018:

You can see that except in a few areas, it’s a sea of red with dots of deep blue. That is not the kind of country that can easily split into regions. Any durable regional split would likely require a mass campaign of ideological cleansing — an analogue to the Partition of India, which killed up to 2 million people.

The U.S. economy could not sustain such a split. Supply chains have become so distributed throughout the country that every region of the country is dependent on a large number of other regions. Here’s a map of food supply chains from Lin et al. (2019):

You can see lots more supply chain maps on the FEW-View website, which shows where each city gets its products from. The short answer is that America is now an incredibly integrated economy in regional terms; any regional separation would cause absolute economic chaos. Additionally, red states would certainly covet the strategic ports of California and the North Atlantic states, while blue states would hunger (literally) after the farmland of the Midwest and Plains states.

All this means you shouldn’t pay too much heed to the people who talk about blue-state GDP vs. red-state GDP, as if this implies the blue side would triumph in a civil war. Yes, blue states, and especially blue cities, produce more of the nation’s output and are home to the nation’s most high-value industries and educated, highly capable workforces. But those industries would be far less lucrative in a “national divorce” scenario; who needs fancy financial products or search ads or the latest brand phone when there’s no food on the table or materials to fix roads? This is not like the 1860s, when the largely self-sufficient North could use its prowess in manufacturing and staple crops to overmatch the agrarian, backward South. The economic supremacy of today’s blue states is based on marginal thinking that would not hold in the case of a large disruption such as a civil war.

Thus, any major civil war is less likely to resemble the war of 1861-65 than the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39. Both sides will try to conquer the whole territory of the United States, and one side will succeed. That would be an incredibly bloody, costly, and savage affair.

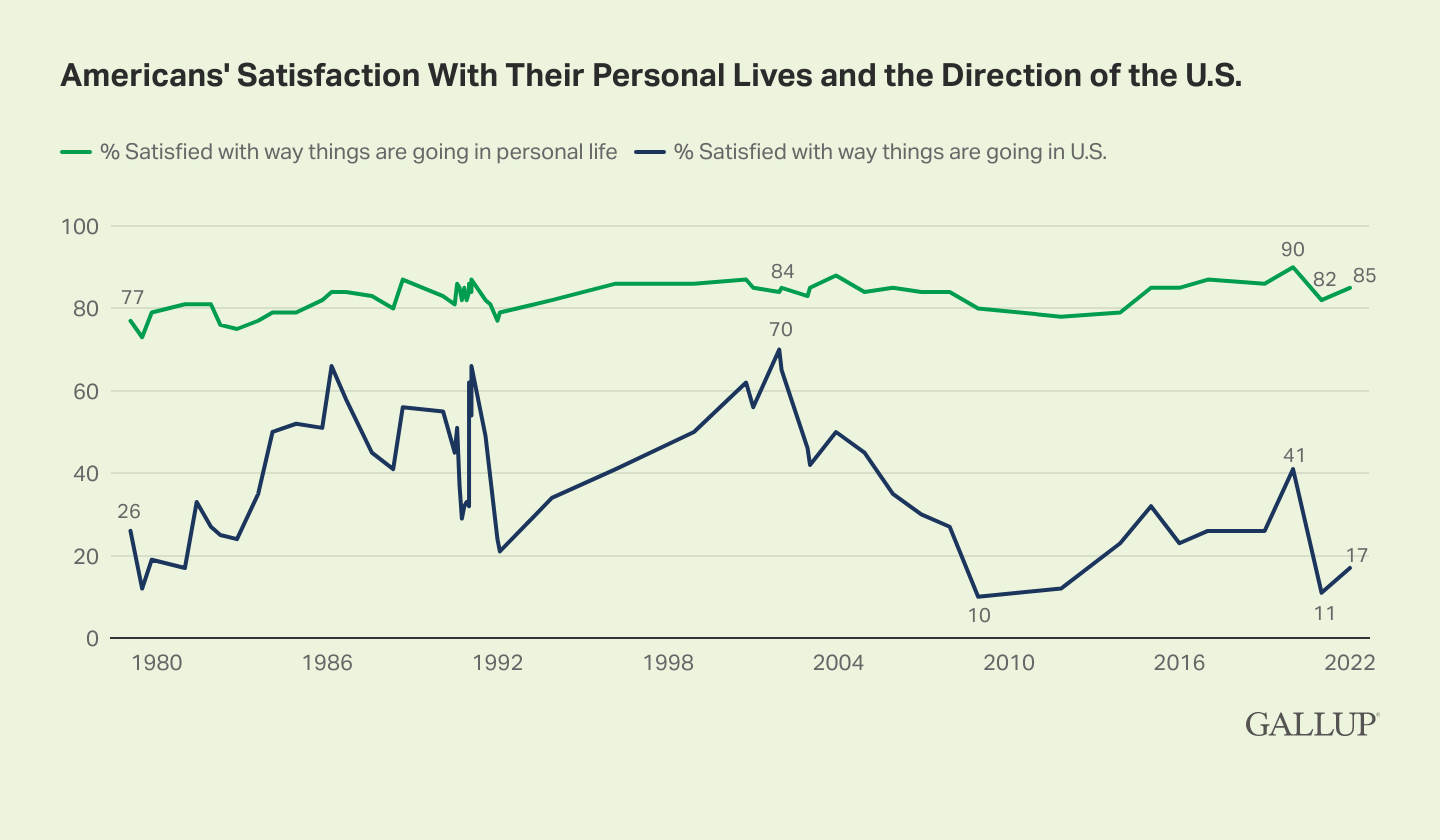

The U.S. is not a chaotic, impoverished nation like pre-civil war Spain, Russia, China, etc. — or even like the U.S. of 1861. It’s a rich nation — one of the richest in the world, even after taking inequality into account. And while most Americans are dissatisfied with the state of the nation, most are satisfied with their own lives:

And polls clearly show that despite the ructions of the past decade, most Americans still like their country.

To throw that away in a civil war would be a tragedy of unprecedented proportions. That doesn’t mean it won’t happen. But it does mean that it’s incumbent on us to do everything we can to find a better path — a way to preserve our nation and live together in peace with people on the “other side” of the political divide.

Democracy, institutionalism, and patriotism

In terms of actual policy steps, I’m not sure what should be done to avert the threats of ideological dystopia, democratic breakdown, and intercommunal violence; that mostly depends on who’s making policy. Reforming the Electoral Count Act is an important step, as are pro-democracy efforts at the state level. But beyond that I don’t have a concrete game plan here.

What I do have are a set of values and ideas that I think will be helpful in holding the nation together.

The first of these is democracy. I’ve long argued that we should see democracy not in terms of narrow electoralism, but as an ideology of political and social inclusion writ large. That doesn’t mean we should equate democracy with “whatever policies my side wants” (though some will inevitably try to do this). Instead, it means that we should adhere to the ideological principle that everyone’s voice deserves to be heard in American politics, and that every American has partial ownership over their country. That means fighting tooth and nail against anti-democratic moves like state legislatures choosing electors. It means working to reduce corrosive but chronic problems like gerrymandering and lack of voter access to polls. But it also means valuing the will of the broad public over the narrow interests of activists; a commitment to democracy necessarily involves some element of “popularism”.

Second, we should commit to defending the integrity of our institutions. This doesn’t mean mindlessly defending things like the filibuster; indeed, the filibuster makes Congress largely incapable of governing, and provides legislators with an excuse to vote in much more partisan ways than they would if their votes really counted. Eliminating the filibuster would strengthen the institution of Congress.

Similarly, progressive rhetoric about blowing up the Supreme Court, in the wake of the Dobbs decision, is extremely unhelpful. In extremis, if there is overwhelming popular support, Congress and the President can “pack” the Court by adding more justices (this is one of the checks and balances in the Constitution), but histrionic demands to strip SCOTUS of its power simply because it made decisions people don’t like simply foment chaos. Similarly, the standard progressive rhetoric about abolishing the Senate is utterly unrealistic and simply makes progressives look like they’re advocating for tearing down the nation.

Finally, we need to embrace patriotism — not hollow flag-waving jingoism, but the kind of substantive, constructive patriotism described by former Obama speechwriter Ben Rhodes:

Every nation is a story…We must tell a captivating story—one concerned primarily with an American identity that is broad and resilient enough to succeed…The greatness of a nation’s story is not invalidated by its flaws…[Obama] was able to succeed politically because he framed the effort to address those flaws not as a repudiation of what it means to be American, but rather as a validation of it.

America, Obama pronounced again and again, was a great country precisely because it gave us the capacity to try to fix what was wrong with us. The failure to try to do so was a betrayal of a civic religion. The flag stands for that; so do protest anthems. The military fights for this very ideal; so do activists who bleed in the streets…

To defeat [the Trumpists’ ethnonationalist] story, we will have to convince enough Americans who do not think of themselves as progressive, or even center-left, that there is an American democracy that needs to be saved.

That’s really the key idea — that there is a country worth saving here. What needs to happen is that the majority who wants to save this country needs to become louder and more confident than the ideologically driven people who want to destroy it and create something else in its place. If we can safely make it through this time of political chaos, America has a bright future ahead of us.

Your comparison to Europe is instructive. Abortion, same sex marriage, etc., all were accomplished democratically in European countries. That has made them not only durable, but has legitimized the results in the eyes of people who opposed them.

In the US, the left took a wrong turn and decided to use the Civil Rights movement as the default way of achieving social change. But that has meant decades of decisions where elites (whether Republican or Democrat, Supreme Court Justices are elites) shoved social change down the throats of the public. In reality, Black civil rights was a *sui generis* problem caused by unique historical circumstances that warranted an atomic bomb response from the Supreme Court. But repeatedly going nuclear on issue after issue—issues that were not unique and which other countries handled democratically—through the Supreme Court tore at the social fabric.

Beautiful article.

One thing this brought to mind is how much I wish conservatives had a better media outlet to voice their arguments than Fox News. The conservative instinct to say, "wait a minute, is this giant social/economic change really a good idea?" is often a healthy thing for liberals to have nearby. We need conservatives the same way Mulder needs Scully. But it helps nothing if people with different political instincts are also working under a different set of facts.