A few economists are starting to think seriously about industrial policy

But not enough researchers are paying attention, and we only know a little so far.

One of my biggest problems with the discipline of economics is how fundamentally reactive it is. Economists tend to study whatever topics are big in the news right now — in the 70s everyone was writing about inflation, in 2009 everyone was scrambling to write papers about how financial crashes could bring down an economy, and so on. Only a few economists tend to have the vision to write about important issues well in advance of when they explode into the mainstream consciousness, and these tend to win Nobel prizes.

If you want to be one of the economists who gets out in front of the crowd, a good idea is to look at countries other than the United States. Japan’s land price collapse in the early 1990s foreshadowed America’s in the late 2000s. Similarly, the success of countries like South Korea in boosting themselves to developed-world status in the late 20th century offers important clues about what a successful industrial policy might look like in the 21st. Now, with industrial policy suddenly in vogue all over the world, all but a few economists are going to find themselves racing to catch up, or risk being left behind by events.

But there are several additional reasons why econ research hasn’t had enough to say about industrial policy. One is that the term itself can mean several different things. For example, it can include:

Government subsidies for specific industries

General government support for specific industries that go way beyond subsidies and may not even include subsidies at all

Unconventional policies like export subsidies that are meant to help new industries develop, but can be used by a wide array of industries that the government doesn’t choose in advance

Tariffs or other protectionist measures

Standard measures like R&D, infrastructure, and education that are already part of the developed-country toolkit, but which can be justified by the benefits they bring to certain industries

When you see people write things like “Why industrial policy fails”, they’re usually talking only about one of these definitions and not the others (if they even know exactly what they’re talking about, which is not always the case). So “industrial policy” is a very slippery term to define, which also makes it harder to use in research papers.

A second difficulty is that what the goals of industrial policy should be isn’t clear, and they vary from country to country and time period to time period. Several possible goals are:

Securing foreign exchange in order to achieve import security of food and energy

Catch-up industrialization in a developing nation

Boosting economic growth and/or employment and wages in a developed nation

Maintaining a military edge over rival countries

Insuring supply chains against the risk of war

Preventing climate change or other negative externalities

So it’s not necessarily easy to compare, say, Korea’s attempts to promote their auto industry in the 1970s with the Biden administration’s attempts to promote decarbonization in the 2020s, because the goals of the two policies overlap only to a modest degree.

Thus, economists really have their work cut out for them in making sense of the tangle of policies and goals that we lump together under the term “industrial policy”. And if American policymakers and pundits in the 2020s simply assume that we should copy what Korea did in the 1970s, because research shows that those policies “worked”, we could end up making big mistakes.

That said, there are some reasons to think that the experience of industrializing countries like 1970s Korea will have some relevance for what the U.S. and other developed nations are trying to do in the 2020s.

First, the advent of new technologies puts every country into a situation that’s somewhat analogous — at least along certain dimensions — to a developing country. In 1967, Korea did not know how to make a viable car industry; they had to figure it out. In 2023, neither the U.S. nor China nor any other country knows how to make a viable A.I. industry, because no one has done that yet; we have to figure it out. The cases aren’t exactly analogous — in 1967 someone had already made a viable car industry, so Korea could import some foreign technology instead of inventing it. But developing-country industrial policy can potentially give us insights about how to turn new inventions into thriving, productive new industries.

Second, the experiences of developing countries can help warn developed countries about potential pitfalls of certain policies, even if the goals aren’t exactly the same. For example, China’s attempt to heavily subsidize its chipmaking and aircraft industries in the 2010s doesn’t seem to have borne much fruit; that might serve as a warning about how industry-specific subsidies can end up generating waste.

And third, many of the competitive dynamics that developing-country industries face might be similar for developed-country industries. Korea trying to break into the global auto market might offer lessons as the U.S. and Japan try to break back into the global chip fabrication market.

Anyway, those are some reasons to think of “industrial policy” as one unified research topic, rather than as a bunch of unrelated topics.

This is basically the working assumption of the Industrial Policy Group, a team of scholars led by Réka Juhász and Nathan Lane. In recent years, they’ve both compiled reviews of past research on industrial policy, and added some of their own. But even more than that, they’ve been trying to make the case that industrial policy is a worthy topic of study. Their two most important papers, and the ones highlighted on their website, are:

“The New Economics of Industrial Policy”, by Juhász, Lane, and Rodrik (2023)

“The Who, What, When, and How of Industrial Policy: A Text-Based Approach”, by Juhász, Lane, Oehlsen, and Pérez (2022)

The first of these is really the one to start with. Juhász, Lane, and Rodrik (2023) offers a sweeping overview of the debate, a literature review, and a summary of the original research in Juhász et al. (2022).

The authors define industrial policy very generally, as any government attempt to shift the industrial structure of an economy. They list some theoretical justifications for why this might be a good idea:

negative externalities like climate change that we want to reduce

positive externalities like idea spillovers and national security that we want to increase

coordination failures, where producers’ productivity depends on the presence of a bunch of other producers nearby

production inputs that have public-goods components, like infrastructure

What’s interesting about the second and third of these justifications is that at least in theory, they can work for essentially all of the potential goals of industrial policy that I listed above. Having government solve a coordination failure or provide a public good might help decarbonize the economy, or grow the economy and raise wages, or strengthen national security, etc. This is why rich countries today might be able to learn some important lessons from what developing countries did in the past.

Note I say “might” because it’s fundamentally an empirical question. These policies might help, or they might crash and burn. But the point here is that there’s no good theoretical reason to believe that industrial policy must always necessarily fail. To economists, that kind of thing can be important!

The authors then address the common critique that government doesn’t have enough information to “pick winners”:

[U]ltimately what is required for industrial policy to work is far less than a consistent ability to pick “winners.” In the presence of uncertainty, both about the effectiveness of policies and the location/magnitude of externalities, the ultimate test is not whether governments can pick “winners,” but whether they have (or can develop) the ability to let “losers” go. As with any portfolio decision, it would be an indication of sub-optimal policy if the government did not back some ventures that end up as failures ex post. In the U.S., Department of Energy loan guarantees to Solyndra, a solar cell manufacturer, failed miserably; but a similar loan guarantee to Tesla enabled the company to avert failure and become the behemoth it is today. In Chile, successes in four projects supported by Fundacion Chile – including most spectacularly salmon – is said to have paid the costs of all other ventures.

Letting losers go may still be a hard task, in light of political pressures that inevitably develop…But it is far less demanding than governmental omniscience.

They point out that past research that supposedly shows the ineffectiveness of industrial policy was actually pretty ambiguous. There’s a fairly large literature showing a negative correlation between subsidies and productivity at the industry level. But Juhász, Lane, and Rodrik point out that while this could be because of inefficient policies and rent-seeking, it could also be that government is directing subsidies to the industries where market failures are the largest. After all, if you look at the correlation between hospital visits and deadly heart attacks, you’ll find a strong positive correlation…but this doesn’t mean that hospitals give people fatal heart attacks!

The authors also warn about conflating industrial policy with protectionism, noting that recent industrial policies have often been aimed at increasing exports and international capital flows:

[S]eeing industrial policy as tantamount to protectionism can omit contemporary forms of industrial policymaking in open economies, where interventions look different from the protectionism of the past. We show below that, more often than not, contemporary policy takes the form of promoting outward-oriented economic activity, say by promoting export activity…

The ascent of the East Asian Tiger economies belies a clean correspondence between protectionism and industrial policy. Notably, 1960s South Korean industrial promotion under Park Chung-hee targeted export activity (Westphal 1990), and measures of trade openness increased through its most conspicuously interventionist periods (Lane 2022). FDI has emerged as a tool for industrial policy targeting (Harrison and Rodriguez-Clare, 2010; Harding, Javorcik, Maggioni 2019).

Despite the breadth of the topic, there have been some attempts to study industrial policy in a generalized, global way. Most of these have used government spending as a measure of industrial policy, but this is a problem, since A) it requires the researchers to basically decide which spending constitutes “industrial policy”, and B) some industrial policies don’t involve spending at all.

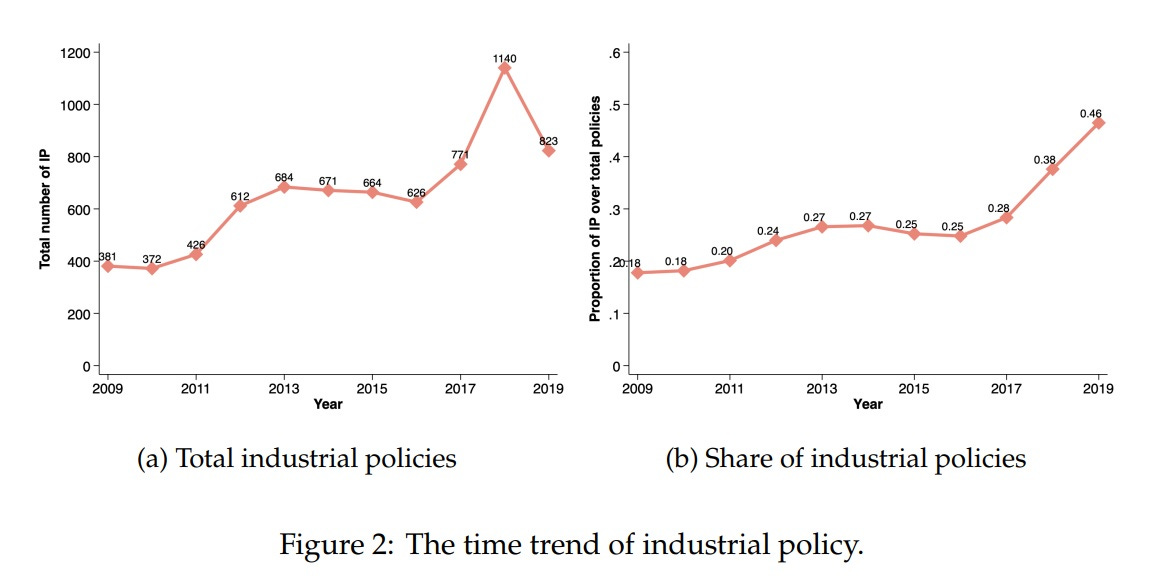

Juhász et al. (2022) instead use machine learning on a database of policies from various countries, systematically classifying which ones seem to be intended as industrial policy. (This method also relies on the authors’ judgement, but is far more systematic and general.) They find that a whole lot of industrial policies are just rich countries trying to help their successful established exporters, and most of that assistance comes in the form of subsidies. They also confirm that industrial policy has been on the rise since the mid-2010s.

This is interesting, but the method is probably too general. Instead, Juhász, Lane, and Rodrik argue that what we really need are carefully identified causal studies of the effects of specific policies in specific countries — the kind of credible empirical research that has become more popular throughout the field of economics in recent years. They describe a few of these studies.

One is Lane’s 2022 paper studying the effects of South Korea’s “heavy and chemical industry drive in the 1970s. Lane finds that the industries targeted by the policy tended to grow faster and gain international market share, even after the policy was ended. He also finds benefits for industries downstream of the targeted ones — for example, Korean auto manufacturers like Hyundai that benefitted in the long term from cheaper steel from Korean steel companies like POSCO. This looks like a case of temporary subsidies leading to permanent productivity improvements, at least in the targeted industries.

Another is Juhasz’s 2018 study of the British blockade during the Napoleonic wars. She finds that industries in French regions that were less exposed to British competition as a result of the blockade ended up being enduringly stronger after the war. This is quite an ironic result in a historical sense, of course, but it shows that protectionism can at least sometimes succeed in shielding the industries it’s meant to protect.

These are just two studies; there are many others, and Juhász, Lane, and Rodrik go through a fairly long list. Most of the papers end up finding some sort of positive effects from industrial policy, though this could be a result of publication bias. In any case, there are enough encouraging findings that taken together, they imply that economists should be taking the idea of industrial policy more seriously than they have so far.

Anyway, Juhász, Lane, and Rodrik’s review goes on to cover various specific types of industrial policy, including infant-industry protection, government promotion of R&D, and various policies used by East Asian countries during their rapid industrialization. They also highlight research on questions like whether public-private partnerships are a good idea, whether manufacturing should be favored over services, and so on.

It’s going to take me a long time to read through all of this research. And there’s plenty more out there that they didn’t catch. For example, Ciuriak has a 2013 literature review on the question of whether exporting makes companies more productive. And Bartik has a 2018 literature review on place-based policies to help manufacturing-intensive regions.

The truth is that all of this still represents only a few tiny slivers of knowledge, and economists as a whole have only begun to scratch the surface of this incredibly important and very timely topic. But at least a few are trying. If and when the global rise of industrial policy eventually forces economists to study it en masse, Réka Juhász, Nathan Lane, and Dani Rodrik will be remembered as the pioneers who broke ground on the topic even before it was cool and sexy.

Interesting article. As always... a few comments...

1) Industrial policy (as classically defined) tends to be "good" for lagging countries where the future trajectory of innovation is understood. Even in this situation, it does not work well unless the industry can find a non-innovation based value (ex cost[China] or quality [Japan]).

2) Long term "industrial policy" is much more driven by the rate of innovation... and this requires quite a bit different machinery... perhaps even societal culture. Totalitarian societies are awful in this regard. Freedom is not just a moral value, but a key economic one as well.

3) The rate of innovation is highly correlated with the ability of a country to attract the world's best talent, an ability to "arm" them with resources, and a society which can accept disruption.

4) Linear economic development can be developed with a follower economy. However, over time an innovation paradigm will generate disruptive changes which lead to accelerated growth.

Finally, economists and any policy based on economic studies tend to miss the impact of these non-linear technology trends. Leading to something like the current situation where there is puzzlement at lowering inflation, raising interest rates, AND economic growth.

I appreciate Noah's highlighting the recently released work of Juhász, Lane, and Rodrik (2023), his observations regarding the reactive tendencies of the economics profession, and laying groundwork for continuing assessments of the what, how, and why of U.S. industrial policy. The authors also posted a two-page summary of their perspective on Project Syndicate, "Economists Reconsider Industrial Policy." https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/new-economic-research-more-favorable-to-industrial-policy-by-dani-rodrik-et-al-2023-08 I offer the following observations as someone who's continuously worked in the U.S. industrial policy realm since 1978:

-- as a summer graduate intern in the industrial policy shop of Carter's Secretary of Commerce;

-- an MIT graduate research assistant (1978-82) to dissertation adviser Ben Harrison (Deindustrialization of America), the Energy Lab's photovoltaics program, and the International Motor Vehicle Program;

-- author of the manufacturing chapter of Ira Magaziner's RI Greenhouse Compact (1983 and the basis for my dissertation);

-- founder of two regional economic development consulting firms (1984-2004) (initial clients of our team: AK Gov. Bill Clinton and Burlington VT Mayor Bernie Sanders);

-- co-author of Brookings brief "Clusters and Competitiveness: A New Federal Role for Stimulating Regional Economies" (2008) which became the basis for EDA's regional industrial clusters program https://www.eda.gov/funding/programs/build-to-scale and which facilitated co-author Karen Mills becoming Obama's SBA Administrator and co-author Elisabeth Reynolds being Biden's supply chain assessment coordinator;

-- Industry Studies Association board member for industrial policy (2020-present) https://www.industrystudies.org/, the outgrowth of the Sloan Industry Studies Network (founded 1990) of 26 centers modeled on the MIT IMVP https://www.industrystudies.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=49:research_centers&catid=19:site-content;

-- co-founder of the ISA's industrial policy webinar series;

-- publisher of the weekly ISA Industrial Policy and Strategy Update; and;

-- as public policy research professor at George Washington University, quarter-time staff to the American Economic Association's committees on government relations and economic statistics and consultant to Third Way's U.S. Clean Energy Industrial Strategy project.

-- From 2004 until industrial policy's revival, my focus was on improving the federal statistical system for economic decision-making and research, with a particular focus on the role of Decennial Census in the allocation of trillions in federal funding; stopping the dismantling of Economic Census, the American Community Survey, and the Survey of Business Owners; and keeping the citizenship question off the 2020 Census.

Observations for discussion:

1) In the capitalist framework, national economic competitiveness depends on the capabiity of the government to provide incentives that move the nation's businesses, the source of its economic well-being, towards greater international competitiveness. To achieve this end, economists apply the tools they know well, that is, they tend to think of industrial policy as top-down economic engineering in which analysts help policymakers determine the quantitative if-thens of competitiveness in individual sectors (e.g., semiconductors) and craft and implement programs based on the perceived if-then dynamics.

2) In practice, the economic engineering approach is difficult to make work for several reasons.

a) As technologies, markets, and each nation's competitiveness constantly change and so throw off the validity of any if-then beliefs as of the moment. The trick is to develop mechanisms that facilitate public-private consensus-building regarding responses to an ever-changing set of issues and opportunities.

i) In practice, it turns out that successful industrial policy relies on the collaborative (public-private) application of the principles of business strategy to each traded industry deemed key, e.g., chips, clean energy, AI. As a consequence, I find "industrial strategy" to be a more appropriate term than "industrial policy," as the latter implies an approach of "set and forget," which in my experience is a recipe for failure.

ii) Among the federal departments, in my view DOE has been the most successful in implementing this approach, largely because it's being headed by a former McKinsey business strategy consultant. See, for example, https://liftoff.energy.gov/ and https://www.energy.gov/policy/securing-americas-clean-energy-supply-chain

iii) Through this lens, an important contribution of the Juhász, Lane, Rodrik paper is the introduction of " the concept of “embedded autonomy,” borrowed from sociologist Peter Evans, to characterize an alternative model of regulation, based on iterative collaboration between government and firms."

iv) Again with DOE, a good example of this approach is Li-Bridge, which is focused on "the development of a robust and secure domestic supply chain for lithium-based batteries." https://www.anl.gov/li-bridge

v) The collaborative strategic approach has been applied successfully at the state and local level for the last 40 years. While it's much more complicated to do at the national scale, the principles are the same.

vi) Until recently, these regional efforts have been deemed "not interesting" by most economists, but that's changing. Dani Rodrik, mentioned earlier, and Gordon Hanson are carrying out the Reimagining the Economy project https://www.hks.harvard.edu/centers/wiener/programs/economy Also see Scott Stern et al. https://www.nber.org/books-and-chapters/role-innovation-and-entrepreneurship-economic-growth

b) While the U.S. has a very good federal economic statistics system for macroeconomic policymaking, it has a lousy one for industrial competitiveness. The latter requires current, reliable industry-specifiic statistics--not only on traditional measures of output, productivity, and wages but also trade in value-added (TiVA)--and we don't have that.

i) At the moment, the value of each import is assigned 100% to the last country that touched it and not allocated among all the nations that contributed value added. As a consequence, we can't satisfactorily measure the nature of U.S. competitiveness vis a vis other nations. Good news -- for FY2023, Congress gave Commerce money to boost TiVA data. https://www.bea.gov/data/special-topics/global-value-chains

ii) The U.S. has two separate systems of economic statistics by industry--one from Census and one from BLS--and about 1/3 of the establishments are assigned one NAICS code by Census and another by BLS. The result, for instance, is that BLS says the U.S. has about 200K chips production workers while Census says it has about 100K. The source of the problem is that Census is authorized to look at IRS tax data and BLS is not, so cannot sit down with Census to reconcile its business register listings with the Census Bureau's. For details, see p. 168 of FY2024 Treasury Green Book https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/General-Explanations-FY2024.pdf

iii) In developing the new Annual Integrated Economic Survey, Census found that about 1/4 of its case study establishments were misclassified in NAICS. This finding led me to ask OMB to direct Census to examine this problem and how it might be addressed, which OMB did in July. See terms of clearance at https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/PRAViewICR?ref_nbr=202303-0607-003

iv) In a piece I wrote for the 2012 CAP series on industrial competitiveness, I discuss these issues but the last, which was new to me. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/economic-intelligence/

Continued in the next comment . . .