A DemTech Economic Agenda: Ten Steps Towards Collective Resilience

A guest post by by Liza Tobin, Warren Wilson, Brady Helwig, and Connor Martin of the Special Competitive Studies Project (SCSP)

One of my big themes this year is been the economic competition shaping up between the U.S. and China. Just in the past week, I’ve written about why this competition is necessary, and how it’s already reshaping U.S. ideas about the best way to run an economy. The next challenge, however, is to determine the actual concrete first steps that the U.S. should take in order to achieve its goals in the industrial policy race. So I asked my friends at the Special Competitive Studies Project — a think tank founded by ex-Google CEO Eric Schmidt to think about exactly these issues — to write a guest post detailing some of the tactics the U.S. should use to increase its economic independence from China over the next few years. Most of their recommendations are about friendshoring — the idea that instead of trying to be an economic island unto itself, the U.S. needs to reshape globalization around trade between countries other than China.

Successfully reducing overdependence on China does not mean the United States should abandon global trade – quite the opposite. While bringing production back to American shores is critical, the U.S. must also strengthen commercial ties with partner countries committed to fair, mutually beneficial economic relationships. Reorienting supply chains away from China and toward partners – a process known as “friendshoring” – will allow the United States to “strengthen[] economic resilience while sustaining the dynamism and productivity growth that comes with economic integration,” according to Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen.

Collective resilience is even more crucial when considering the critical technologies, like AI, that democracies must lead because of their disproportionate impact on national security, economic prosperity, and individual expression. The United States and its allies and partners share a strategic and economic imperative to retain assured access to key inputs for these technologies.

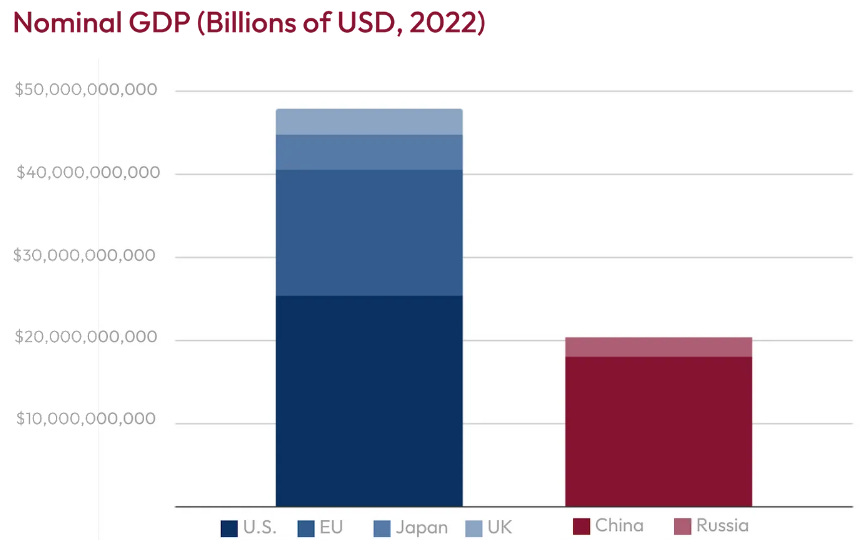

As SCSP has pointed out before, friendshoring makes both economic and diplomatic sense. America’s global alliance network is one of its greatest asymmetric advantages vis-a-vis China; equally, bringing back all essential production to American shores would be inefficient and impractical. Democracies together account for 60 percent of global GDP compared to China’s 20 percent, and according to recent survey data, 69 percent of American and 72 percent of EU respondents said trade relationships should be based on “shared values.”

To date, however, Beijing has out-organized its democratic rivals through a brute force approach that can fracture democracies’ quantitative advantage. Time is short, and we may not get a second chance. America needs to get bolder and better organized around an approach that combines selective disentanglement from China with concrete steps to boost collective resilience with like-minded countries.

Here are ten action items:

Treat reshoring and friendshoring as complementary. Even as America builds up its domestic production capacity in key inputs like microelectronics and EV batteries, it can work simultaneously with allies and partners to build production elsewhere. Allied countries and their firms will continue to compete for market share in the industries of the future. While competition within a rules-based framework is healthy, however, remaining defenseless against China’s chokeholds over a host of goods is not. Bringing jobs and industries back to the United States is the gold standard, but it is not always possible. America should adopt a “both-and” approach, competing vigorously with its friends while also recognizing that investments in other partner countries are beneficial in the long term. To do this, American policymakers should negotiate new trade and supply chain arrangements with partner countries, consulting closely with U.S. stakeholders to ensure these new relationships reflect America’s strategic and economic interests.

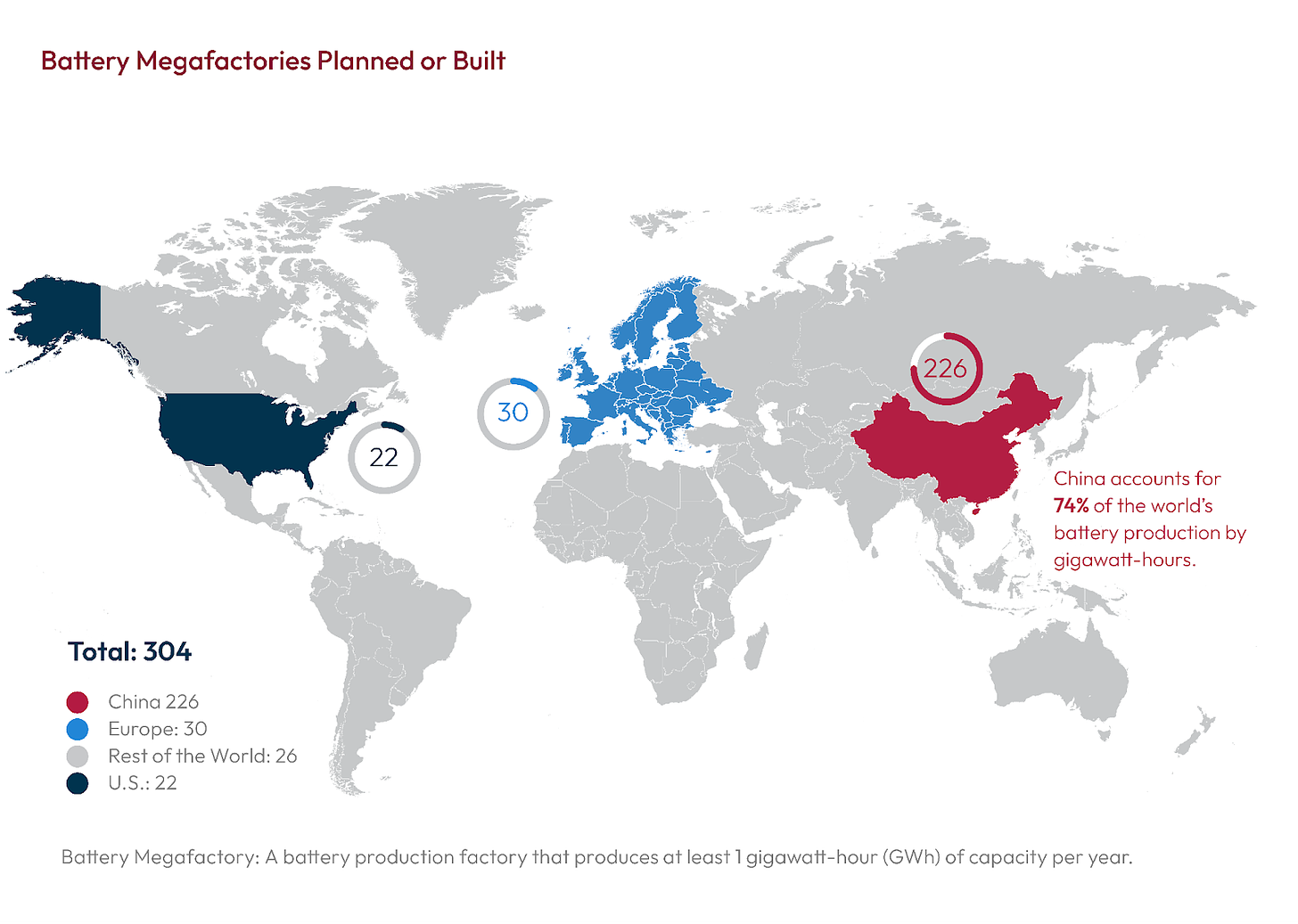

Expand “China guardrails” – and add friendshoring incentives. An innovative feature of both the CHIPS & Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), so-called guardrails have discouraged the recipients of government incentives from investing in the expansion of China’s semiconductor industry and encouraged domestic sourcing for raw materials. IRA incentives have created a boom for domestic battery supply chains, while CHIPS guardrails will help ensure companies do not double down on production in China. Going forward, America and its allies should adapt and apply these guardrails in other tech sectors, including addressing security concerns associated with electronics supply chains and diversifying production of the full hardware stack for advanced networks like 5G and 6G out of China. New guardrails for additional sectors should account for the strategic value of friendshoring by offering incentives for production in allied countries (albeit less than those for domestic projects). Guardrails and incentives could be extended to sectors including open source hardware, biotechnology, and flat panel displays. Government adoption of AI-powered monitoring and compliance tools can ensure the guardrails are data-driven, effective, and efficient.

Strategically leverage market access. Many of America’s allies and partners are more dependent on trade with China than is the United States. As a result, they will be reluctant to turn away from the China market without an alternative source of demand. Conversely, without easier access to export markets, American firms might also miss significant opportunities in emerging and developing markets which could drive much of the world’s future GDP growth. America’s ultimate leverage is access to the U.S. market – the largest source of consumer demand in the world – which could be offered in mutually beneficial arrangements. New, major trade agreements are currently stalled in Washington, but policymakers can start by advancing narrowly focused solutions that benefit both the U.S. and our allies. For example, the Biden Administration could bolster the underdeveloped trade pillar of its Indo-Pacific Economic Framework and move towards digital trade agreements by 1) harmonizing rules on data privacy and localization and 2) agreeing on AI governance principles that could help facilitate trusted trade flows, especially as generative AI begins to unleash rapid changes in digital commerce. Washington should also accelerate trade talks with Taiwan and include reducing double taxation – which inhibits two-way investment at a time when Taiwanese investment in U.S. semiconductor production is more important than ever – as an agenda item.

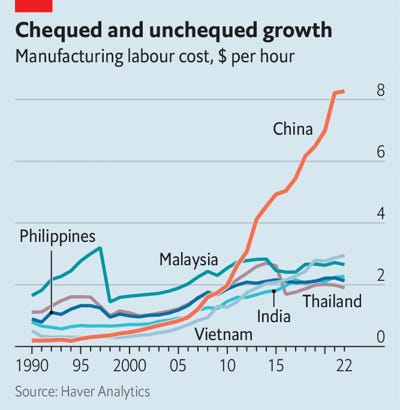

Diversify to “Altasia.” Labor costs in China have long since outstripped those of many of its neighbors. Geopolitics plus the effect of rising wages are driving many firms to look to “Altasia” – a network of countries including emerging Southeast Asian powers like Vietnam and Indonesia, as well as South Asian giants India and Bangladesh. Taken together, “Altasia” has a labor force nearly 50 percent larger than China’s. When reshoring is not feasible, the United States and its allies and partners should encourage their private sectors to shift investments out of China and towards this network of countries and beyond. Such a shift would offer competitive advantages once found only in China, without risking businesses’ IP and subjecting their operations to the Chinese Communist Party’s interference.

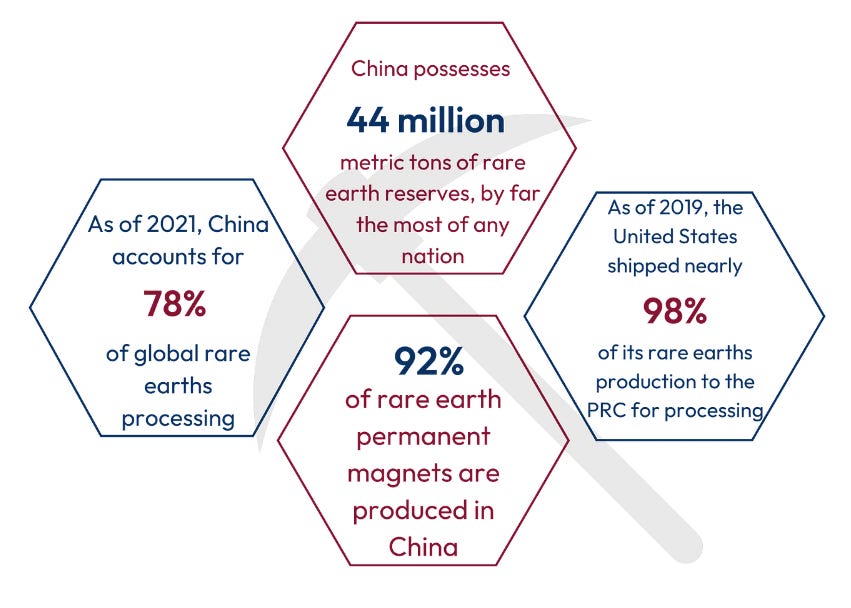

Look upstream. Rare earths and other critical minerals offer a prime example of a sector where friendshoring is likely to occupy the lion’s share of a diversification effort. Over the next two decades, demand for lithium, cobalt, and nickel is projected to grow by 4,200 percent, 2,100 percent, and 1,900 percent, respectively; demand for rare earths is projected to increase by 700 percent. Meeting such massive demand increases will require opening many new mines and processing facilities both domestically and abroad. Breakthroughs in processes to recycle rare earth minerals offer prospects to boost domestic production. The U.S. and its allies and partners have a shared interest in these goals. Talks on forming a critical minerals buyers club composed of trade agreements between the U.S., EU, Japan, and the UK are a positive step. Key tools to sustain this momentum include 1) bolstering the State Department’s Mineral Security Partnership to support efforts like its engagement with African governments and 2) encouraging U.S. aid and financing agencies, like the U.S. Development Finance Corporation (DFC), to pursue more minerals sector investments, as well as granting them flexibility to take on additional risk.

Sources: Kelsi Van Veen & Alex Melton, Rare Earth Elements Supply Chains, Part 1: An Update on Global Production and Trade, U.S. International Trade Commission (2020); Does China Pose a Threat to Global Rare Earth Supply Chains?, China Power, Center for Strategic and International Studies (2021)

Create a Tech Export Accelerator. While the U.S. continues to focus on “crowding in” private investment domestically, it can also do more to match U.S. tech solutions and financing with buyers abroad. Despite having cutting-edge tech firms and numerous financing tools, America struggles to package technology exports and investments in a way that can compete with turnkey PRC offerings like Huawei’s 5G and digital infrastructure exports. Programs and incentives are spread around an alphabet soup of different agencies (e.g., DFC, the U.S. Export-Import Bank, the Departments of State and Commerce, U.S. Trade and Development Agency, USAID’s Digital Invest). These programs are confusing to navigate, particularly for small and medium-sized firms. Establishing a one-stop matchmaking service could bridge the gap. Dedicated and knowledgeable professionals, supported by AI APIs for customer service, would connect the dots between U.S. firms, foreign buyers, government incentives, and assistance from U.S. Embassies abroad. A moonshot version of this Accelerator could also connect with similar incentive programs in allied and partner countries.

Build common sense national security safeguards together. Washington has worked hard over the past several years to align its approach with allies and partners, such as the EU, on national security guardrails like inbound investment screening. As the Biden Administration reportedly prepares to roll out a new outbound investment regime, it must likewise seek to forge a common approach that prevents loopholes which Beijing can exploit. The U.S. and its allies and partners should also build on the momentum of last year’s joint export controls targeting Russia and Belarus by developing a new approach to export controls that accounts for today’s challenges. Existing multilateral export control frameworks are outdated relics of the Cold War era built to address problems like WMD, not problems posed by the PRC’s efforts to dominate emerging technologies. The United States should lead the development of a plurilateral export control regime that leverages smaller, more nimble groupings in specific technology sectors, like quantum or AI. Among their many potential policy applications, AI tools hold tremendous promise for export controls – for example, AI models could be fine-tuned on open-source and other relevant information to help streamline export control authorities’ targeting, licensing, and enforcement processes, easing the burden on governments.

Take cues from allies. Washington can learn from allies’ moves and make strategic decisions in alignment with them where it makes sense. For example, Tokyo recently adopted economic security legislation that has lessons to offer. These include its use of subsidies to incentivize companies to reshore from China, as well as actor-agnostic public messaging that focuses on practical action steps. Between 2020 and 2022, the number of Japanese firms in China fell from 13,600 to 12,700. Australia has created a government strategy for the critical minerals industry, encouraging public-private collaboration as it moves toward its goal of building a “sovereign industrial base.”

Stop saying “decoupling.” Total and abrupt “decoupling” from China is neither practical nor necessary, short of a military conflict. Instead, Washington and its allies should be concentrating on the most feasible path to selective disentanglement – a concept more likely to resonate with allies and the private sector than the dramatic term “decoupling.” Selective disentanglement should aim to reduce overexposure to China in domains where interdependence puts our national security at risk, like critical infrastructure and supply chains for key technology inputs.

Look to the future and invest in offsets early. Opportunities exist to wean dependence on China with innovative, over-the-horizon grand challenges. Ideas could include 3D-printed or rare earth-free magnets, biomanufacturing methods for critical minerals like lithium, exploring novel paradigms for microelectronics that could power next-generation AI models, securing supply chains to enable the bold goals in biotechnology that the Biden Administration has articulated, developing alternatives to PRC-produced components for advanced networks, and using AI to develop more cost-effective molecules for industrial chemistry. The United States and its allies and partners must begin working now to secure supplies or develop offsets for the inputs that will power the next generation of platform technologies – and America’s current lead in generative AI can accelerate all of these efforts.

These steps can accelerate progress towards assured supply of critical technology inputs, ensuring that Americans and their fellow citizens in like-minded nations can benefit from a fairer and stronger global trade regime amidst a shifting geopolitical landscape – and that businesses in these countries can continue to compete while protecting themselves from the risk Beijing poses to their interests. By working together, America and its friends can strengthen their collective resilience and deliver prosperity to their citizens.

Such well written and explanatory words that are common sense solutions worthy of exploring. Time is of the essence.

Interesting, so Altasia won't even need to be allied, as long as it's there, it's not in China