This post was originally a thread on X, but a lot of people liked it, so I thought I should redo it for my blog. It’s about Japanese cities — and in particular, about one special kind of Japanese retail space that most other countries lack.

I hang around with a lot of urbanists, and pretty much all urbanists love mixed-use development — shops and restaurants coexisting alongside houses and apartments. But mixed-use development comes in different forms, and Japan does things a bit differently from most of the world’s large, dense cities.

In this post I’m going to distinguish between two types of mixed-use development. Shop-top development, which is common in dense cities all over the world, puts apartment buildings on top of restaurants and stores. Zakkyo buildings, which are a kind of development seen mostly in Japan, have stores on all the floors.

My argument, basically, is that zakkyo buildings are at least partly responsible for many of the features that make Japanese cities such a consumer paradise. But before I lay out that case, I want to show some pictures that demonstrate how the rest of the world currently approaches urban retail.

Shop-top development: apartments above shops

Most of the mixed-use development in downtowns around the world feature shops and restaurants on the first floor, with apartments (or, sometimes, offices) on the floors above. This is called “shop-top” or “over-store” housing, and it has basically become the standard version of mixed-use development for dense, built-up areas.

Shop-top housing is extremely common in New York City. Here’s an example from Little Italy in NYC — you can see the storefronts on the ground level, with apartment windows above:

Here’s the iconic neighborhood of Greenwich Village. It shows exactly the same pattern:

Shop-top development is also the norm in my city of San Francisco:

It isn’t just the U.S., though. Here’s the Marais neighborhood in Paris:

And here’s the Rue Montorgueil:

In both of these, you can clearly see that the shops are on the ground floor, and the upper floors are apartments (or, in some cases, possibly offices).

Here’s London:

Here’s Istanbul:

Even many Asian megacities favor shop-top development. Here’s Tsim Sha Tsui, a bustling commercial district in Hong Kong:

For a lot of Western travelers, Asian megacities seem similar, because they all have a lot of electric signs.1 But look closely, and you’ll see that in many of these cities, the signs are only for first-floor shops. Here’s Mong Kok in Hong Kong:

Anyway, by now you get the picture. Most of the great cities of the world have created dense downtown shopping districts by putting apartment buildings over shops and restaurants.

These shop-top neighborhoods are, generally speaking, very walkable, vibrant, and pleasant. But they’re not the only way to do mixed-use development. Japan has pioneered an alternative.

Zakkyo: Shops above other shops

The word “zakkyo” in Japanese is often translated as “mixed use”. But what it really refers to are buildings — generally of 3 to 8 stories — containing a wide variety of restaurants, shops, and offices. They look like this:

The book Emergent Tokyo, by Jorge Almazan, Joe McReynolds, Naoki Saito, et al. has a great section on the history of how zakkyo buildings came to be so common in Tokyo and other Japanese cities. A shorter version is in McReynolds (2022):

In a tall, narrow zakkyo building, each floor can potentially hold multiple microbusinesses, collectively giving Tokyo a rich vertical dimension beyond mere high-rise offices and residences…Zakkyo buildings often appear in train station commercial districts, where land prices are high but potential customers are numerous…Whereas in most cities around the world a building’s commercial uses are located on its ground floors along the street, zakkyo buildings accommodate commercial functions vertically on all levels. Entering the upper floors of a zakkyo building, one might find a restaurant, an internet café, a health clinic, a hostess club, and a language school all in the same building, without any particular hierarchy or organizing principle…A single narrow zakkyo building can sometimes host as many as 80 distinct microbusinesses[.]

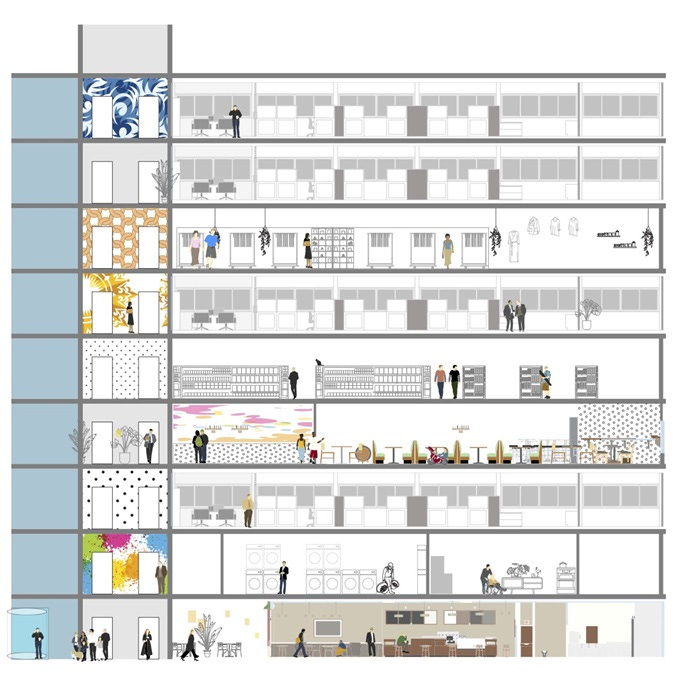

Zakkyo buildings are basically vertical strip-malls for urban pedestrians. Here’s a helpful diagram of what the interior of a zakkyo might look like, from an article by Jeffery Tompkins:

Zakkyo buildings have two special features. These are:

Visible signs for the buildings on the upper floors

Stairways and elevators that are directly accessible from the street

These special features share a single purpose: to allow pedestrians to discover and access the upper-floor shops very easily. The signs make it easy to see the shops on the upper floors as you walk by. The elevators and stairs make it easy to reach those shops without going through a lobby.

The signs are certainly the most distinctive visual identifier of zakkyo buildings. They’re usually lit up at night, giving Japanese cities their iconic “forest of lights” appearance:

But the stairways and elevators, though far less visible, are no less important. They significantly shrink the size of zakkyo buildings, allowing more to fit in a given area.2 And they make it extremely easy and convenient for passers-by to walk over and try out the restaurants and stores on the higher floors.

How zakkyo make Japanese cities great

Zakkyo buildings’ advantages go far beyond pretty lightscapes. They’re part of the explanation for why Japanese cities are so vibrant and enchanting for people all over the world.

Zakkyo buildings increase a neighborhood’s commercial density — the number of shops within a given surface area. If you stack businesses on top of other businesses instead of putting them all on the ground floor, you can fit more businesses into every square kilometer (or square mile). This increases variety for consumers — for a given amount of effort, you can try out a lot more different things.

Imagine there are 100 shops in an area, and each shop is 20 feet wide. If we put all the shops at ground level, you’ll have to walk 2000 feet to see all the shops. But if we stack the shops on top of each other, in zakkyo buildings four stories high, you’ll only have to walk 500 feet to see all the shops. That’s a lot easier on your feet, and it takes less time. You’re more likely to make a 500-foot walk than a 2000-foot walk, meaning in a zakkyo neighborhood you’re likely to encounter a greater variety of shops than in a neighborhood where everyone is on the first floor.

That variety also increases serendipity. Most consumers don’t just randomly wander the streets. They have a destination in mind — a restaurant they want to eat at, a store they want to shop at, etc. If all the shops in a city are very spread out, consumers heading to their destination won’t accidentally encounter many new, unknown shops along the way.

But if retail businesses are clustered tightly together, there’s a substantial chance that you’ll see one that looks new and enticing, and thus discover a new place you like. Zakkyo buildings thus increase novelty, by helping you have more such happy accidents. And for retail businesses, this manifests as an increase in customer acquisition. When an area has a larger number of shops, more customers will be walking the streets in that area.

In sum, zakkyo buildings are part of the reason why Japan is such a consumer paradise. Greater Tokyo has 160,000 restaurants, compared to only 13,000 in Paris and 25,000 in NYC. Some of that is because of the Japanese government’s strong support for small retail businesses. But some of it is probably due to zakkyo buildings making it possible to sustain more small independent shops.

On top of all that, I think zakkyo buildings offer another big benefit to Japanese cities. By concentrating retail customers, they allow quiet residential neighborhoods to exist very near the city center.

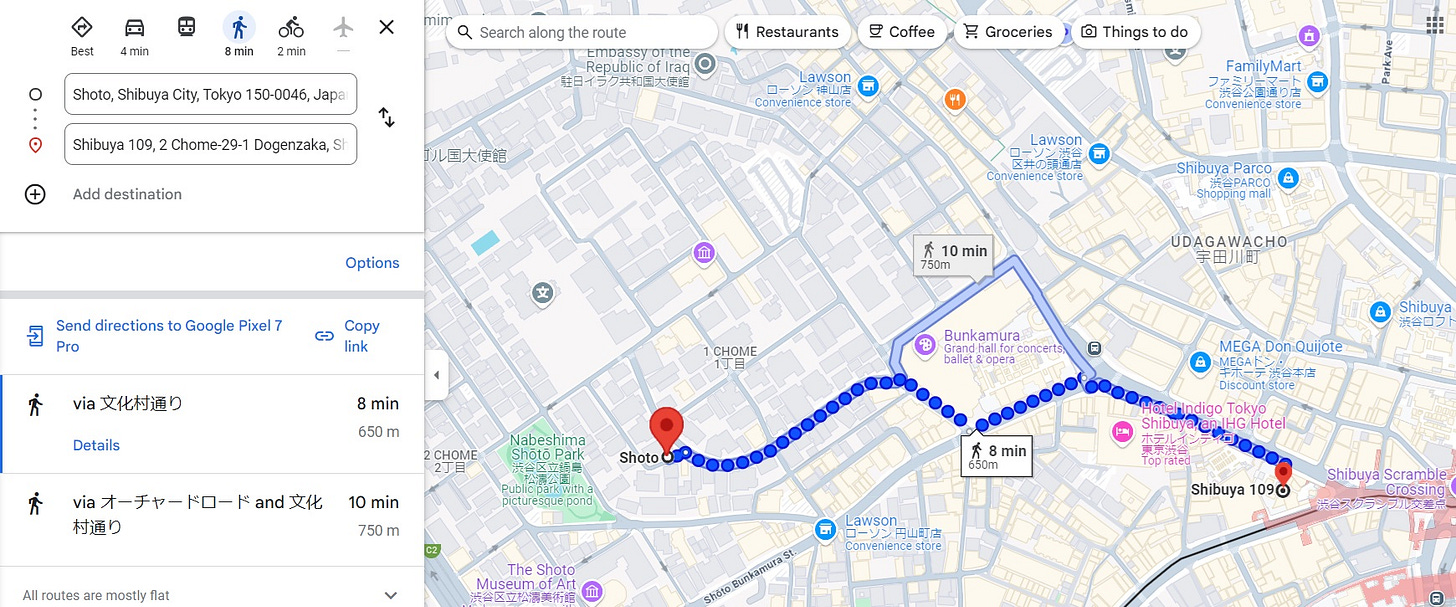

Consider these two pictures. The first photo is of a major intersection in the middle of Shibuya, one of Tokyo’s most famous (and most famously crowded) shopping districts. You can see Shibuya 109, a famous shopping mall. The second photo is of a peaceful little park called Nabeshima, in the middle of a quiet, leafy, upscale residential area called Shōtō:

And yet here’s the wild thing: Shōtō and Shibuya 109 are just an eight-minute walk away from each other!

This isn’t actually that unusual for a Japanese city. There are islands of peace and quiet just a few minutes’ walk from even the loudest and most bustling shopping districts.

Part of this is due to careful urban planning, but part, I think, is due to zakkyo (and to other forms of hyper-concentrated retail). Concentrating vast numbers of shoppers in a few small areas means that fewer of them will be walking through the quiet residential neighborhoods.

(Of course, San Francisco does this too — there are plenty of quiet, leafy areas with quiet, mostly-empty streets. Some of these areas are close to streets with lots of retail. But SF only manages to do this because small businesses are so few and far between; Tokyo is able to achieve comparable results while having far more retail per capita.)

So I think that many of the delightful and distinctive features of Japanese cities owe their existence in part to the zakkyo pattern of mixed-use development.

How can American cities get zakkyo buildings?

The advent of zakkyo buildings in America would require some cultural getting used to, but I think most Americans would greatly appreciate them. Residents of NYC — and of the dense central areas of other cities like SF and Chicago — might not realize it, but if their cities became a bit more like Tokyo, they would enjoy it.

In fact, NYC already has a (very) few scattered zakkyo buildings. Here are three in Koreatown:

And here’s a random building in Brooklyn that looks awfully like a zakkyo:

And here’s one in Flushing, Queens:

These don’t look quite as nice as the ones in Japan, but they’re great nonetheless. Their existence proves that American cities aren’t too dangerous for zakkyo buildings (or at least, not all of them). They also prove that Americans are not culturally repulsed by multi-floor retail buildings.

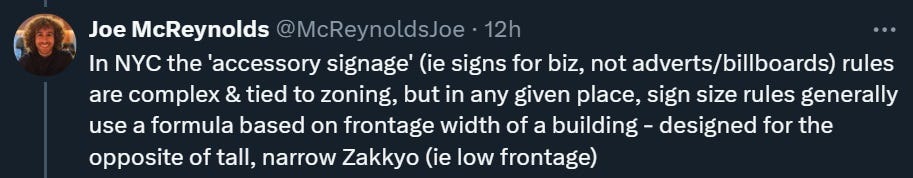

How can America get more zakkyo buildings? Zoning is obviously important, just as it is for everything America needs to build in its cities. Regulations should also make sure to allow stairs and elevators fronting the street. But Joe McReynolds suggests an additional idea: loosen regulations on the signs businesses are able to put on their buildings.

That sounds like a great idea to me.

Right now, I think the most important thing is just education. Japan has invented — partly by accident — a really new and innovative way to organize urban retail. Urbanists and city planners need to know that. They should all know the word “zakkyo”, and they should all realize that shop-top housing is not the only possible way to do mixed-use development.

We usually call these “neon signs”, even though almost none of them are neon now; almost all are just an LED or a light bulb behind a colored piece of plastic. But in Hong Kong, there are still a few classic neon signs.

This is the same principle behind the single-stair reforms that are gaining in popularity across the United States.

Another benefit of zakkyo buildings is the balance of discoverability of the higher floors. Shops on those floors are discoverable when walking by due to the signage, but aren't as discoverable as ground floor businesses, which creates a class of somewhat less desirable commercial space that is still extremely conveniently located, which allows a neighborhood to support a wider range of businesses, and allows for very thin margin and hobby project businesses to survive even in more expensive areas.

Something I'm curious if zakkyo helps with is business survivability and turnover. The significant number of small businesses is one clue, but how much turnover is there in Tokyo businesses compared to other cities? If a case could be made that zakkyo has a quantifiable effect on small businesses surviving longer than 2 years that may be a much stronger argument for adoption than the ones you mentioned (even if I find those reasons appealing, too).