2023 is when the empires strike back

Cold War 2 won't be decided by the opening moves.

I still remember a time at dinner with some friends last year, when I was recounting the series of mistakes that Xi Jinping had made in terms of managing China’s economy and foreign policy. One friend had to leave early, and on his way out the door, he turned to me and said “Well, now I know I don’t need to worry about China.”

He was wrong, and I wish I hadn’t given him that impression.

2022 saw authoritarian powers suddenly on the back foot. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was a military and geopolitical disaster, and Xi’s economic mismanagement brought China’s growth to a momentary halt. Meanwhile, the U.S. started looking a bit more politically stable and started to take action to preserve its remaining industrial advantages, Asian democracies like Japan and the fast-growing India continued to flex their muscle, and Europe seemed more united than it had in…well, ever. All of this naturally had some people in the West optimistic that Cold War 2 would ultimately end much like World War 2 and the first Cold War.

Unfortunately, early optimism can easily give way to complacency and cockiness. We’re still in the opening moves of Cold War 2, and the minor victories of 2022 are likely to revert to the mean. 2023 is already shaping up to be a year in which the authoritarian powers recalibrate their strategy and find their footing.

The first part of China and Russia’s comeback consists of simply not giving up. At a recent summit in Moscow, China and Russia affirmed their close partnership and their shared commitment to the goal of overturning the world order built by the developed democracies.

If you haven’t watched the video of the meeting between Xi and Putin, I think you really should. Sure, anyone can roll out a big red carpet and hang some fancy chandeliers. But the pomp and splendor clearly communicates these leaders’ view of their countries as grand, august powers:

As long as China and Russia hang together, neither one will ever be truly “isolated” by anything the U.S. and its allies do. Although China has publicly promised not to sell arms to Russia, international relations scholar Paul Poast argues persuasively that the two countries should now be regarded as allies. (Personally, I prefer the word “axis”, which signifies a more arm’s-length partnership of ideologically aligned powers. But I digress.)

Building on that base of unshaken resolve and shared goals, China and Russia are both working feverishly to correct the mistakes they made in 2022. For Russia, that means hanging onto its territorial gains in Ukraine and keeping its economy afloat. China, however, can afford far greater ambitions. In addition to scrapping Zero Covid and attempting to re-float its property market, China will spend the next year building international support for its vision of the global future.

A non-ideological Cold War

Americans need to realize that Cold War 2 is fundamentally unlike Cold War 1 or World War 2. Those 20th century contests were ideological battles, where people fought and died for communism, fascism, and liberal democracy. But China is not an ideological, proselytizing power; its ideology, basically is just “China”. Xi Jinping doesn’t care whether you have elections and protect civil rights or send minorities to the death camps, as long as you support Chinese hegemony abroad.

Cold War 2 is therefore a bit more like World War 1 — a naked contest of national power and interests. And if the U.S. tries to turn it into an ideological battle, it could backfire. Mark Leonard of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute writes:

Western leaders believe that they are defending the rules-based order [and] that the world is polarising between rule-bound democracies and aggressive autocracies…

[But] the idea that Western governments are preserving the rules-based order is not persuasive to many around the world, considering that Western governments themselves have already abandoned it on many fronts…

Biden has committed himself to the narrative that the world is divided between democracies and autocracies, implying that those in the middle should be persuaded or pressured to choose sides. But most countries reject that idea and instead see the world moving towards deeper fragmentation and multipolarity. Countries like India, Turkey, South Africa and Brazil see themselves as sovereign powers with the right to build their own relationships, not as swing states obliged to placate other powers…While the United States is betting on a polarised world, China is doing everything it can to advance a more fragmented one.

Leonard expresses skepticism about how much fruit this approach will bear for China, and he has a point. Already, the Belt and Road project has been an international fiasco. And China’s bullying approach toward India, Vietnam, and the Philippines — all of whose territory China claims — has prompted those countries to seek balancing coalitions with each other, as well as with Japan and the U.S. In investment-starved countries like Brazil, a flood of Chinese money might buy some rhetorical victories, but eventually those politically driven investments will probably go the way of the Belt and Road and leave a sour taste in their wake.

But recently, China had a genuine major diplomatic success, when it brokered a deal that warmed relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran. This suited China’s own interests, of course — it cemented Iran as a Chinese ally and drew Saudi Arabia away from the U.S. orbit. But it was also a genuinely good thing for the Middle East and for the world. The multi-decade cold war between Iran and Saudi Arabia had torn apart the region and led to highly destructive proxy wars like the one in Yemen; the U.S., with its long-standing vendetta towards Iran, had been unable to calm things down. Now China has, and even the U.S. government is quietly applauding. This will help the world forget the days of the “wolf warriors” that damaged China’s image with their bellicosity.

And war in the Middle East is not the only global problem that China is helping to solve. Although China is by far the world’s biggest greenhouse polluter (thanks to its coal industry), it is also by far the world’s biggest investor in green energy:

When cheap solar, batteries, and wind deliver a future of clean energy abundance for the countries of the world, we will have China to thank. The U.S. did most of the R&D for these technologies, but China is the one that scaled them and drove down their costs.

These genuinely good achievements of China’s don’t mean that its influence in the world is positive overall — if that were true, we wouldn’t have any reason to prosecute Cold War 2. The world China wants to create would ultimately be worse for the independence and territorial integrity of small and poor nations than the world the developed democracies created after WW2.

But what this does mean is that the U.S. won’t be able to count on most countries seeing Cold War 2 as a struggle of good vs. evil. Even U.S. allies like France may not perceive a moral dimension to the conflict. Instead they’ll see it more like World War 1, and ask themselves how they can maximize their own autonomy and prerogatives in the shadows of the superpower struggle. That’s why even though human rights and democracy are important, Mark Leonard wisely advises the U.S. not to put ideology at the center of its appeal:

Instead of lecturing (or hectoring) non-Western countries, [Western policymakers] ought to acknowledge that everyone has their own interests, which will not always align perfectly with Western interests. Heterogeneity must be accepted as a structural fact, rather than being framed as a problem to fix.

By being less preachy about how other countries run their affairs, and by treating them as sovereign actors with their own priorities, the West can still effect constructive change on specific global issues—and maybe even pick up some new supporters along the way.

It seems likely that the U.S. will take a number of years to make this mental adjustment, which is one reason I think 2023 will lead to at least a modest rebound in China’s image and geopolitical clout.

China’s clustering advantage

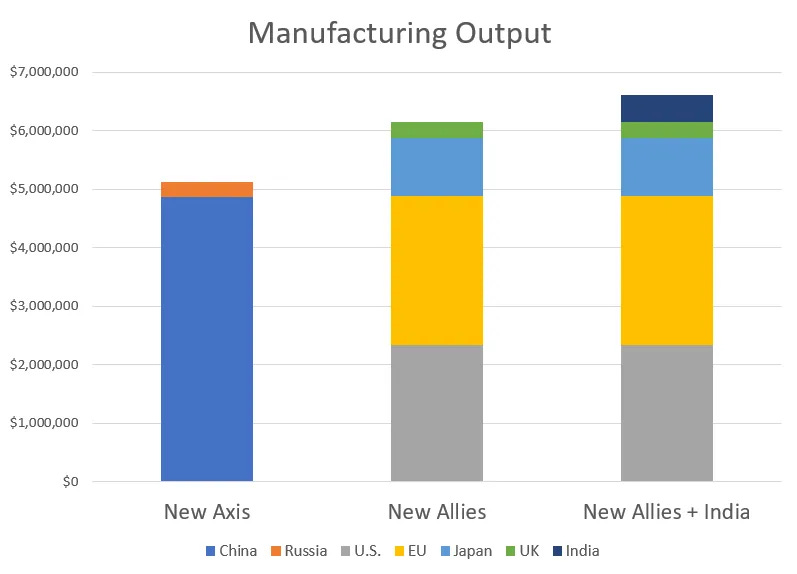

Fundamentally, though, China’s geopolitical (and military) power rest on the foundation of its economic power. When you think about Cold War 2, I want you to always remember this graph:

China does about as much manufacturing as all of the developed democracies combined. That gives it the power to bribe key actors around the world, threaten critics with removal of market access, and bedazzle poor countries with waves of investment. It also gives China the power to out-produce its rivals in a protracted arms race.

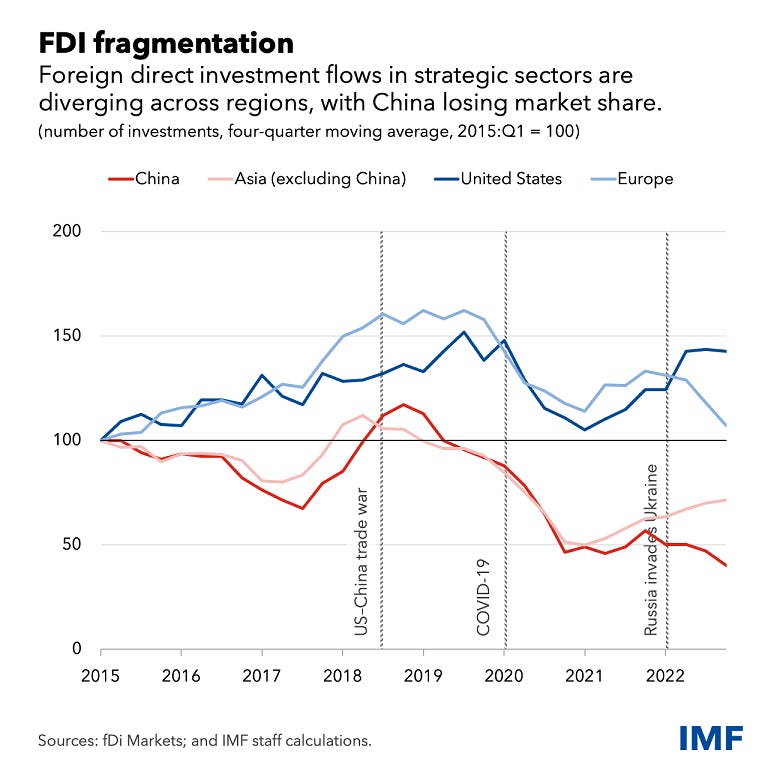

The developed democracies have tried to fight back against Chinese manufacturing supremacy by implementing policies aimed at decoupling — holding back the most advanced tech from China, and providing incentives for multinational companies to shift production out of China. And some decoupling is certainly happening:

But this is an uphill battle, because of clustering effects. China’s concentration of manufacturing know-how, dense network of suppliers, and massive scale make it an easy push-button solution for any company that doesn’t want to think too hard about where to make its products. Agglomeration effects — the fact that every company wants to be close to China’s mouth-wateringly-huge consumer market — are also important. Tesla’s recent decision to build a giant battery factory in Shanghai illustrates the power of these deep economic forces.

This is why decoupling is such a difficult task. Persuading companies to think about making products anywhere but China is going to take time and effort and carefully crafted incentives. It’s also going to take active cooperation between the U.S., the other developed democracies in Asia and Europe, and neutral or friendly developing countries. That runs counter not just to decades of built-up instinct — who can forget the trade wars between the U.S. and Japan in the 80s, or Trump’s tariffs on allies in the 2010s? — but to the U.S.’ ongoing protectionist backlash. For example, the U.S. recently failed to renew a trade deal with developing countries in Southeast Asia, causing some manufacturers who had fled China to shift production back there. We’re a long way from the point where “friend-shoring” becomes more than a slogan.

Thus, China’s strategy to recover from its economic missteps will simply be to loudly remind the world that they are “the make-everything country”. The idea will be to reset the world’s mental clock to 2019 — before Covid, before the real estate crash, before Xi’s crackdown on the IT industry — and sort of pick up where things left off, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of economic inevitability. Foreign portfolio investment will help China bail out its local governments’ and citizens’ financial losses from the real estate crash, while manufacturing FDI will bolster employment and help restore growth.

I expect this approach to succeed modestly. It won’t restore China’s long real estate boom, nor will it raise China’s productivity growth. China may return to 4-5% growth for a short while, but its rapid catch-up days are done. However, leaning hard on its existing strength as a manufacturing cluster will let China prevent decoupling from becoming a stampede, restore modest growth, and win various allies within the Western business community.

Russia is much bigger than Ukraine

So I think China will recover at least somewhat from the diplomatic and economic setbacks it suffered in 2022. As for Russia, its task is much harder — it has committed itself to an all-out war in Ukraine that it looks ill-positioned to win. There’s no end in sight for the sanctions the West levied against it, and lower oil prices are wreaking havoc on the country’s budget. The Xi-Putin summit looked impressive, but many observers noted that it marks Russia’s descent into a satellite state of China.

That said, Russia will probably manage to avoid outright defeat in the Ukraine war. The recently linked documents show that Ukraine simply doesn’t have the manpower or the ammunition to launch an overwhelming offensive that pushes Russia out of the occupied territories. Russia will keep limping along, mobilizing men as needed, depending on Chinese parts and equipment to keep a trickle of war production going, selling oil to China and India at a discount to fund its eternal war effort.

Of course, Ukraine doesn’t look likely to collapse either — their population is completely committed to the fight, they’ve shown they can defeat Russia’s offensives, and the U.S. public is still strongly committed to providing aid. But it does mean that Russia’s massive strategic blunder and battlefield defeats in 2022 will not result in a rapid collapse of Russian power, as some had hoped.

In other words, 2022 was likely a bit of a false dawn for liberal democracy’s chances in Cold War 2. It exposed real weaknesses in the authoritarian bloc. But those weaknesses exist alongside real strengths — China’s manufacturing supremacy and amoral diplomacy, and Russia’s dogged stubbornness — which have now begun to show in 2023. There should be no doubt that this contest is going to be a long, hard slog for the U.S. and its allies. It will not be over soon, and there’s a serious chance it might not end in success.

Bracing read. Good thing we’re taking the threat seriously instead of committing so much political energy to culture war and other wedge issues…

Maybe a more salient external threat will act as a force of cohesion within Western countries? We just took that test the last few years though and the results in the end didn’t seem that great.

Great post as usual. But I wonder about your point that "China is not an ideological, proselytizing power; its ideology, basically is just 'China'” -- I think there *is* an ideological component to this, regarding the importance (or relative unimportance) of the individual, which China believes the US worships to the nation's detriment. I read Chinese state news daily and this is the leitmotif. I think this is what you mean by China's ideology is 'China,' yes. And I wonder about Russian ideology in comparison -- you spend a bit less time on it.